This post was contributed by Professor Stephen Wright, of Birkbeck’s Department of Economics, Mathematics and Statistics.

I am a Remainer. As an economist the arguments for staying in the EU seem to me pretty clearly to outweigh the arguments for leaving. As a private individual I also clearly benefit from the EU. Polish carers look after my 97-year old mother (very well). I work in multiethnic and prosperous London. I have a Serbian-Dutch prospective son-in-law. I travel quite often in Europe and like the cheap flights (who doesn’t?). And the Central and Eastern Europeans who serve my coffee at the station are so polite and efficient.

But when personal incentives coincide with intellectual arguments we need to be careful. When I criticised the pro-Brexit arguments of Patrick Minford of Cardiff University in an email he responded that my arguments were a “metro-elite rant”. He had a point.

I quote from his email (my insertions in parentheses for clarity)

The problem is the balance between skilled and unskilled (migrants) and the complete lack of control that affects large swathes of the country with pressure from large numbers of

unskilled (migrant) workers: effects on housing, hospitals and schools, not to speak of wages (though evidence here is hard to get). Look, if the elite will not compensate these guys they must expect a political explosion which they have now got.

I reiterate: I am, and remain, a Remainer. But Patrick does have a point. If we Remainers do not take these arguments seriously, and – ideally – try to persuade policymakers to do something about these problems – there is a very serious risk that the Brexiteers will win the vote.

One chart, from the LSE’s John Van Reenen and co-authors (See Footnote 1) tells most of the story.

Source: CEP analysis of Labour Force Survey. Wadsworth et al. (2016: 7). Notes: Median wage is deflated by the CPI.

And, as with so many charts, the story that it tells depends on your perspective. From the perspective of a UK-born worker at the lower end of the distribution what they can see, without any advice from expert economists, is that the real value of their wages has fallen almost continuously (by around 10% for someone on the median wage –See Footnote 2) since the peak before the crisis. They can also see, without the aid of the chart (who cannot?) that at the same time the share of EU migrants in the population has risen steadily. And, inevitably they draw a link between the two phenomena.

Van Reenen and co-authors point out (quite correctly) that the share of EU migrants had been rising well before real wages started falling, indeed, as the chart shows, during a period in which real wages were still rising steadily. They also point to a range of evidence showing a lack of a link between EU migration and UK-born wages or unemployment. And they reiterate the arguments that Brexit would lower GDP via reduced trade, job losses, and higher prices of imported goods.

So should we just dismiss the arguments about EU migration as xenophobic scaremongering? Well of course a lot of it is pretty unpleasant, and often verges on the xenophobic. But that does not mean we can simply dismiss the arguments out of hand.

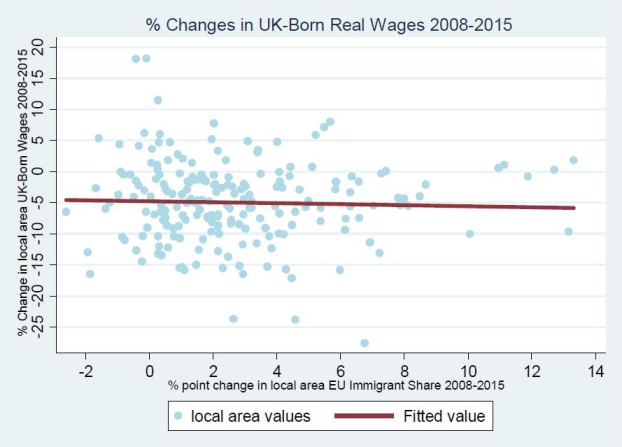

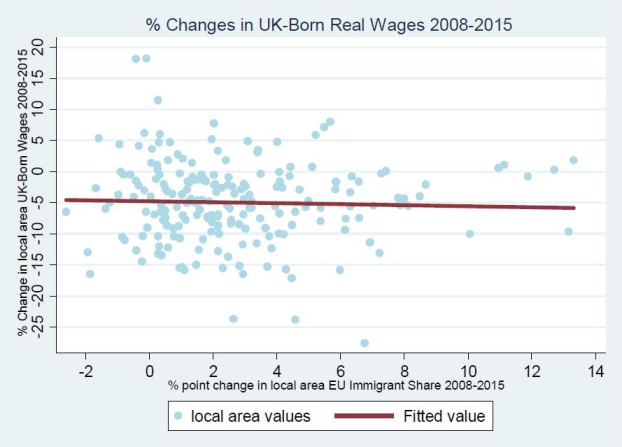

Wages and unemployment, first of all. Is the case against a link proven by the lack of a correlation? Here is one of the charts that Van Reenen and co-authors use to make their case.

Source: CEP analysis of Labour Force Survey. Wadsworth et al. (2016: 10).

Notes: Each dot represents a UK local authority. The solid line is the predicted ‘best fit’ from a regression of local authority percentage change in wages on the local authority change in share of EU immigrants. These are weighted by the sample population in each area. Slope of this line is -0.08 with standard error of 0.15, statistically insignificantly different from zero.

This shows that there has been essentially a zero correlation between changes in real wages in any given local authority and the increase in EU migration in the same local authority. Case proven, it seems.

But pause, just for a moment. Basic statistics courses teach that “correlation need not imply causation”. But there is a subtler version: lack of correlation need not imply lack of causation. Here’s a simple argument (which is easy to substantiate with a couple of lines of algebra).

Suppose that real wages at a regional level tend to be stronger (which in recent years typically means to fall less rapidly than the average – look at the y-axis on the chart) where the regional economy is stronger. And suppose that EU migrants know this. Where will they tend to move to in the UK? Well, to the more prosperous regions, of course. Now suppose that the Remain arguments are correct, and more EU migrants do not have any effect on wages. If that was the case, then we should expect to see a positive correlation in the scatter diagram, but we do not. Whereas if EU migrants do depress wages, this would dampen the positive relationship and possibly result in no correlation at all. Which is what we see in the chart.

Now Van Reenen and his co-authors are all excellent econometricians so they all know this kind of argument perfectly well. Which makes their arguments all the more disingenuous. I’m not claiming that this proves there has been a serious impact on wages. There has been plenty of more sophisticated research which suggests it is hard to find an impact either way (and which Minford acknowledges in the quote above). But that does not in itself prove the argument wrong.

What about hospitals and schools? Well here the Remain argument is on the face of it much stronger. Van Reenen and others have shown that EU migrants are pretty clearly net contributors to the public purse. But the only problem with this argument to the UK-born worker is that there is no direct observable impact of these higher tax receipts on hospitals and schools. We do not have labels on CT scanners or smart whiteboards saying “these facilities were paid for using the extra tax receipts from EU migrants paypackets”. All they can see is the queues and the letters assigning their child to a school two bus rides away.

And finally, of course, housing. Well here of course, all the economists agree. And the policymakers. Everyone agrees. Absolutely everyone. We must build more houses.

But we don’t. Or at least not enough. Nor have we, for decades. As a result, UK households spend more on housing, per square metre of residential land, then any other European country except Luxembourg (See Footnote 3).

Does EU migration make things worse? Well of course it must do. (Even Nigel Farage can be right once in a while.) The CEP paper documents that the number of EU migrants in the UK rose by 2.4 million between 1995 and 2015. That accounts for roughly one third of the total growth of population in the UK over that period. And meanwhile, as Bank of England governor Mark Carney pointed out back in 2014, the UK builds half as many houses each year as Canada despite having twice the population.

No one disagrees that this is crazy. Yet neither the government nor the opposition have made any move to do anything serious about it. Despite the fact that bringing down the cost of housing could be the most effective way (and possibly the only effective way) of raising living standards for UK workers in the medium to long term.

But don’t get me started on housing. It is a serious, a very serious problem, that goes way beyond arguments about Brexit. But, I reiterate, EU migration must be making it worse.

Does all of this mean that I think we should stop EU migration? (Even if we could, which is of course debatable, even post-Brexit). It does not. Despite the fact that, as I noted at the start, my personal interests coincide with my professional judgement, I stick with that judgement. The EU brings benefits. EU migrants bring benefits. To me, and people like me, especially. To the economy on average, almost certainly. But not to everyone.

Pro-Remain policymakers need to start thinking fast about acknowledging this, and how to offer something to the poor and dispossessed of this country to compensate them explicitly for the costs of EU migration. This would not be impossible: remember the last-ditch crossparty promises before the Scottish vote? Maybe these made a difference, maybe they didn’t. But it is worth a try. Very soon it will be too late.

Find out more

Courses at the Department of Economics, Mathematics and Statistics

Images sourced from Wadsworth, J., Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G., Van Reenen, J., and Vaitilingam, R. (2016) ‘Brexit and the Impact of Immigration on the UK’. CEP BREXIT ANALYSIS NO. 5. Available online, last retrieved 13 June 2016.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Birkbeck

Footnotes

- “Brexit and the Impact of Immigration on the UK”, Jonathan Wadsworth, Swati Dhingra, Gianmarco Ottaviano and John Van Reenen, CEP Brexit Analysis No. 5.

- The CEP document shows that the fall for those on the 10th decile has been somewhat larger, and started

earlier.

- De La Porte Simonsen, L and Wright, S (2016) “Residential Land Supply in 27 EU Countries: Pigovian Controls or Nimbyism?, paper presented to Birkbeck Centre for Applied Macroeconomics Annual Workshop, May 2016.

y with a population of over 65 million, it feels absurd that a few hundred thousand fewer workers would create such a problem for the UK labour market. In fact, the issue is more localized than it seems.

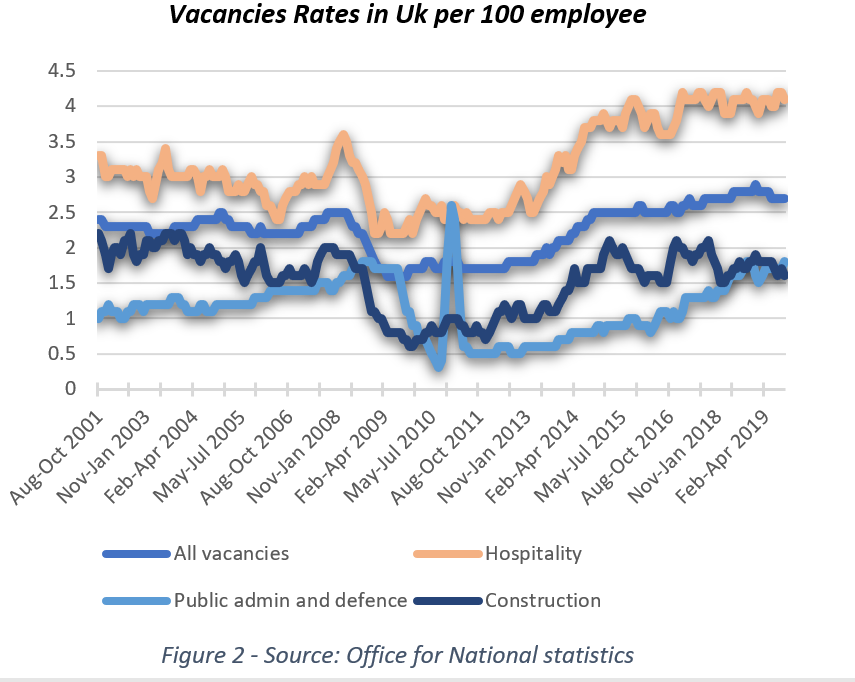

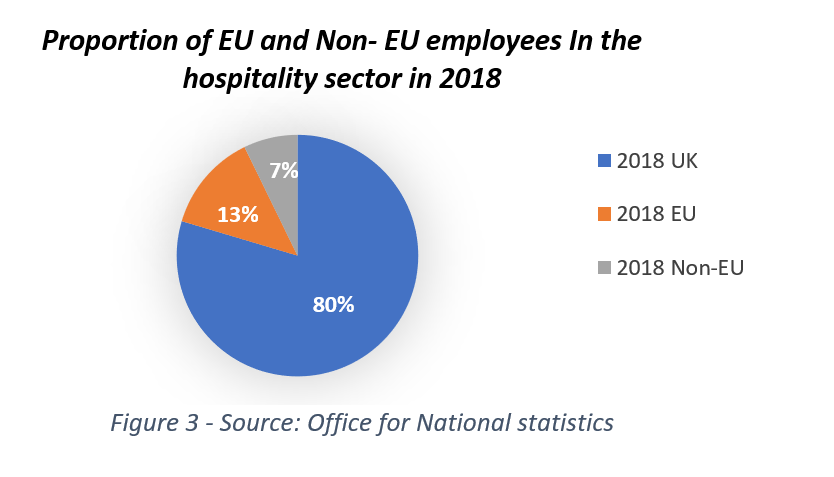

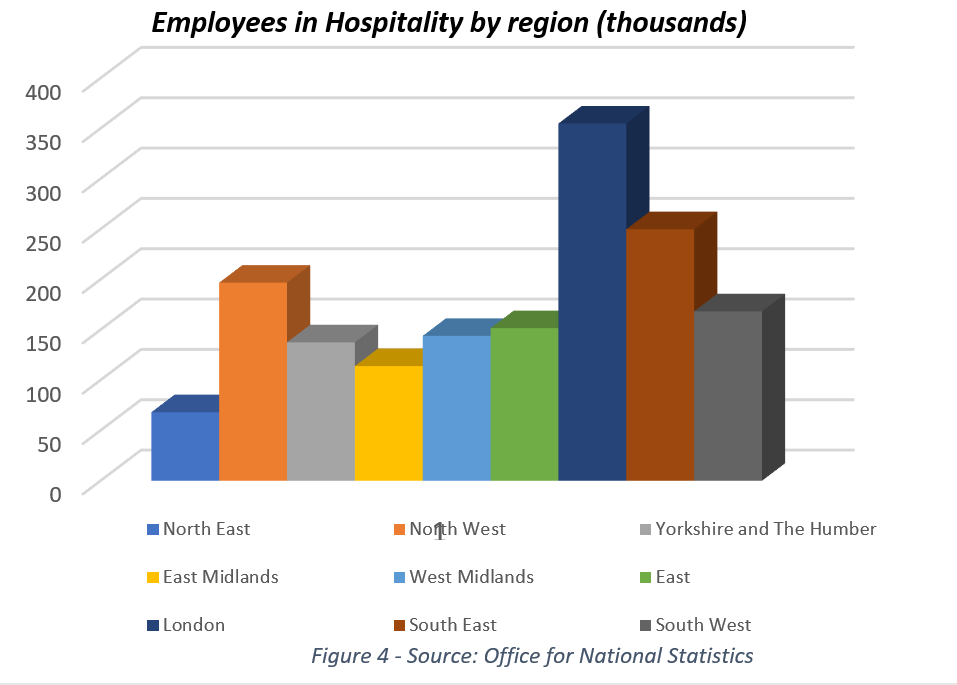

y with a population of over 65 million, it feels absurd that a few hundred thousand fewer workers would create such a problem for the UK labour market. In fact, the issue is more localized than it seems. London and the East Midlands have the highest number of employees in hospitality and almost half of them come from EU countries. In a situation where the number of vacancies is rising, but the pool from which businesses fill their positions is shrinking, it will become harder to find employees in certain areas of the UK. Businesses (who can afford it) will be forced to increase salaries to make jobs more appetising or share the tasks between fewer people and leave certain positions unfilled, which can cause distress and decrease the quality of the job done.

London and the East Midlands have the highest number of employees in hospitality and almost half of them come from EU countries. In a situation where the number of vacancies is rising, but the pool from which businesses fill their positions is shrinking, it will become harder to find employees in certain areas of the UK. Businesses (who can afford it) will be forced to increase salaries to make jobs more appetising or share the tasks between fewer people and leave certain positions unfilled, which can cause distress and decrease the quality of the job done.