Ahead of the Arts Week event ‘Stranger than Fiction‘ about London Diarists on Wednesday 21 May, Birkbeck academics share who their favourite diarists are, and why. Please use the comments section to tell us about your favourite diarists.

Book M

Sue Wiseman, Professor of Seventeenth-Century Literature

My favourite London diarist is Katherine Austen. Next time you go to Shoreditch consider stopping for a moment at Austin Street, next to St.Leonard’s church. You will be where much of Austen’s diary-notebook, ‘Book M’, was written in the second half of the seventeenth century.

My favourite London diarist is Katherine Austen. Next time you go to Shoreditch consider stopping for a moment at Austin Street, next to St.Leonard’s church. You will be where much of Austen’s diary-notebook, ‘Book M’, was written in the second half of the seventeenth century.

Some of London’s most celebrated diarists, such as Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, were writing during the Restoration, when Austen was writing hers. Like Pepys, Austen was a successful and enterprising Londoner, but her voice and concerns add a new dimension to our understanding of Restoration scribbling. Austen had a substantial house in Shoreditch, an area that mixed poor houses, orchard and newly enclosed land. She notes her accounts in ‘Book M’ and is clearly prosperous, but she is pious and almost superstitious too. However, she also had strong views, railing against the ‘abominable rudeness’ of ‘Mr. C’ (he owed her money) and complaining that sending her son to university simply meant that he learned ‘ill-breeding and unaccomplishments’ at his Oxford College. As a young, rich, widow she worried about whether or not to marry again. ‘The world may think I tread upon Roses’, she wrote, but ‘they know not’.

I came across Austen’s ‘Book M’ in the manuscripts room at the British Library. Intrigued by the ‘M’ I ordered it up. My attention was immediately caught by a prose passage concerning ‘a Fall off a Tree where I was sitting in contentment’. The description of the fall was followed by a poem in which she claims that spirits, ‘the crew of Beelzebub’, were responsible for the accident. (You can read the passage and poem here.) Why had Katherine Austen gone from Shoreditch to Essex? Did most seventeenth-century women climb trees for fun? What made her think that the tree was inhabited by ‘revolted spirits’? Was it? I wanted to know and read on slowly, stumbling over her handwriting.

Churchyard at Tillingham

By the end of the day I knew that she had fled to Essex to avoid the plague. She comments that plague ‘is not yet’ in ‘my house’, but it is a race against time. She notes ‘Aug 28th 1665: on going to Essex … the day before I went there . . .was dead that week 7400.’ Soon after this the scene of the diary shifts to the village of Tillingham, Essex. She does not record what she thought and saw as she left the safety of her house to travel East through the poor, plague-racked eastern suburbs to ford the Lea and escape. But it may be that the plague travelled silently with her. For a mysterious physician and suitor that she took with her on her journey died while she was there and is buried in Tillingham churchyard (see here for a walk in Tillingham). Austen survived to return to London and pursue her many plans.

I left the Manuscripts Room that day excited but sad. How could this fascinating writer ever get the readers she deserved? Luckily it turned out that several other people had been at work and now there are two editions of ‘Book M’, one for easier reading and the other for scholarly detail. Maybe someone will find books ‘A’ to ‘L’. I hope so.

Diary at the Centre of the Earth

Dennis Duncan, Lecturer in Modern Literature and Culture

My favourite London diarist is still writing today. In fact they’re a current undergraduate at Birkbeck. Actually, it’s one of my personal supervisees. This feels like an awkward confession. I have never discussed with him the fact that I read his diary. It always seems like an inappropriate digression in the context of the supervision session, like a psychoanalyst asking a novelist patient to sign their book. But let it be known henceforth that I have long been an admirer of Dickon Edwards’s online Diary at the Centre of the Earth.

Edwards describes his diary as ‘sporadic and slightly celebrated’, although there is characteristic modesty in both these descriptions. The Diary at the Centre of the Earth has been maintained since 1997, making it one of the longest-running internet diaries around, and it’s more than a little celebrated (indeed it contributes a fair few entries to Elborough’s London Year). Edwards’s delicate prose elegantly captures the life of a twenty-first-century flâneur, partaking of, and sometimes contributing to, the cultural life of the capital. It has its dandyish moments – Edwards is quite at home with the Soho in-crowd, and his writing has the precision of the Wildean bon mot. Yet for the most part this precision is gentle rather than ostentatious. Diary at the Centre of the Earth describes an attempt to experience London, in its brash, brand-conscious, contemporary configuration, through the aesthetic sensibilities of an earlier age. Its sentences are shot through with a wistfulness at the difficulty of maintaining the illusion.

There is, of course, another more specific pleasure in reading this diary, which comes about when Edwards describes his studies at Birkbeck – a subject he addresses frequently. Here, for me, is the thrill of an intimate association with the narrative – places I inhabit every day, courses I’ve taught, texts I know inside out – caught in the diarist’s lens, assigned a place alongside other, more decadent staples of Edwards’s unfolding life story.

The cat is out of the bag now. Perhaps next time we meet for supervision we’ll make small talk about the parties and private views Edwards has attended most recently. But I think I’d prefer it if we don’t; I’d prefer simply to admire the diary from a distance, to glimpse Edwards’s life – at least his life beyond the purview of a personal supervisor – only through the careful charm of his prose.

The Brixton Diaries

Joe Brooker, Reader in Modern Literature

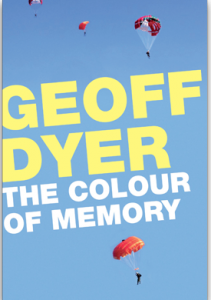

Geoff Dyer’s first novel, The Colour of Memory (1989), began life as ‘The Brixton Diaries’. In 1986 Dyer was commissioned by the New Statesman to write about life as he and his friends were experiencing it in South London. In a note to the revised edition of his novel (2012), Dyer recalls that it was hoped that the diary would have ‘an interest that was more than local and personal’. But what had been a factual writing commission subtly became a fictional writing project: ‘Gradually I saw a way of using and shaping the material in a slightly different way, in a form that would deploy it to better, more personal ends (I invented a sister for myself, or for my narrator, rather) and, hopefully, more lasting effect’.

Geoff Dyer’s first novel, The Colour of Memory (1989), began life as ‘The Brixton Diaries’. In 1986 Dyer was commissioned by the New Statesman to write about life as he and his friends were experiencing it in South London. In a note to the revised edition of his novel (2012), Dyer recalls that it was hoped that the diary would have ‘an interest that was more than local and personal’. But what had been a factual writing commission subtly became a fictional writing project: ‘Gradually I saw a way of using and shaping the material in a slightly different way, in a form that would deploy it to better, more personal ends (I invented a sister for myself, or for my narrator, rather) and, hopefully, more lasting effect’.

The Brixton Diaries had recorded facts from his real life, whereas the novel takes liberties: introducing invented characters, but also clouding the Dyeresque narrator himself in fiction and leaving him nameless and unidentifiable with the author. In a late twist, it appears that the entire narrative is to be taken as written by a character who has appeared in the third person throughout it. The move renders the novel a teasing paradox, a metafictional circle in the key of Calvino or Borges. But we note that Dyer, in retrospect, presents the shift from diary to novel as a move to a more personal mode of writing. It seems that the Brixton Diaries sought public resonance, as reportage from a riot-scarred area of London during Margaret Thatcher’s third term of office; whereas their metamorphosis into fiction somehow allowed Dyer to write a more truly subjective account of the times.

In any case, The Colour of Memory’s roots in diary are unmistakable. The novel recounts the events of a year in Brixton, around 1986-7, essentially in chronological order. It is divided into sixty chapters which count down from 060 to 000. This device lends the book an obscure suspense, but as Dyer admits, suspenseful narrative was not his forte nor his aim: ‘The book did not start out as a novel (and, for anyone expecting a plot, never adequately became one)’. Each small vignette – involving the theft of the narrator’s car, a party, or a trip to Brixton market – could just about claim to include narrative, and certain tendencies grow through the book, notably the fear of crime which culminates in a mugging. But by most standards, The Colour of Memory is distinguished by the absence of narrative, or at any rate of any plot that soars beyond the plausible. The novel’s fascination is with the texture of life, unmomentous yet constant.

This fascination sometimes takes the idiom of photography: the book declares itself to be ‘like an album of snaps’, in which ‘what happens accidentally, unintentionally, at the edges or in the margins of pictures – the apparently irrelevant detail – lends the photograph its special meaning’. Dyer’s book was thus a rarity: an English novel that not merely relayed but formally embodied the advanced continental ideas of the time, in this case those of Roland Barthes’ late work on photography Camera Lucida (1980). In its hospitality to contingency, it also stands as an ambiguous text, between the genres of personal journal and narrative fiction. The Colour of Memory invites us to think about the common ground occupied by the novel and the diary: that less public and celebrated genre that has so often nourished fiction.

(Birkbeck’s Centre for Contemporary Literature will hold a day conference on the work of Geoff Dyer on 11 July 2014.)