By Joanna Bourke, Professor Emerita of History, Birkbeck, University of London and author of Birkbeck: 200 Years of Radical Learning (OUP, 2023).

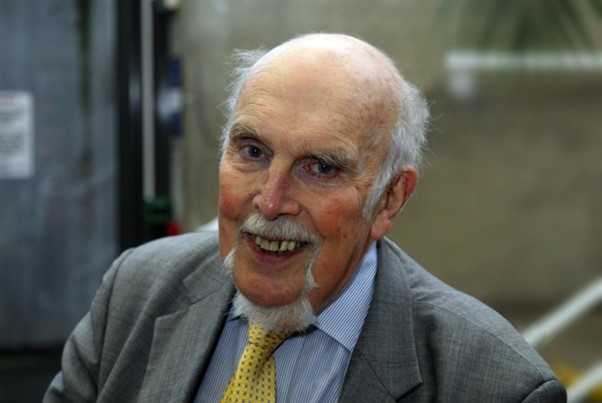

Bernard Crick was one of the most distinguished British political scientists of the twentieth century and a self-proclaimed polemicist. He established the Department of Sociology and Politics at Birkbeck in 1972 and was its Chair until he took early retirement in 1984. In those thirteen years, Crick transformed Birkbeck’s intellectual and political character, leaving behind one of the most respected Politics Departments in the country.

Crick was born in 1929 and died in 2008, at the age of 79. He studied Economics at University College, London, before moving to the LSE to complete his doctorate, awarded in 1952 and published in 1958 under the title The American Science of Politics. It was a critique of the behaviourist streak of American politics. Although he taught in many American universities (including Harvard, McGill, and Berkeley in the 1950s), his first permanent academic posts were at the LSE and then the University of Sheffield. In 1972, however, he was appointed to Birkbeck to establish the college’s first Department of Politics and Sociology.

Crick was thrilled to be appointed at Birkbeck. He had been commuting to Sheffield from London for years and was relieved to be back in his home-city. He was also a strong supporter of adult education, believing that it was important for students of sociology and politics to have practical experience in the ‘real world’. One of his early messages after arriving at Birkbeck was to inform prospective applicants that ‘candidates from a first degree into which they came straight from school will not usually be considered’! He also thought that adult students improved the entire learning experience. Crick always argued that a university ‘should be a creative sharing, not a departmentalisation of learning’, as he put it in Political Thoughts and Polemics (1990).

For Crick, politics was ‘ethics done in public’. This aphorism was another way of saying that he was an enthusiastic advocate of the unity of theory and practice. This was why, during his editorship of The Political Quarterly, he made it into a leading forum for debate about political theory as well as practice. The entire raison d’être of academic politics was to forge an engaged citizenry. Indeed, the fate of democracy lay with people’s civic literacy, which is why Crick was dismayed by the profound political ignorance of most Britons.

Not surprisingly, Crick was a pragmatist. ‘Real’ politics was messy. It had to deal with the vast diversity of competing and conflicting interests, as well as being unpredictable, which is one reason Crick argued against the ‘scientistic’ behaviourism of many North American schools of political thought. His emphasis was on politics-and-society, rather than political science, with its emphasis on abstracted data rather than social values and meaning. Effective politics involved negotiating, compromising, and seeking consensus. In other words, the world of politics was about reconciling differences. As Crick wrote in 1971, political science had to be ‘aware of the inextricable relationship of theory to practice and hence the need for political relevance’. He quipped that ‘the world may not need political science… but political science needs to be relevant to the world to be profound as a discipline’.

Crick refused to identify with doctrinaire partisans of either the Left or Right but contended in In Defence of Politics that political scientists should ‘argue only for relevance’, retaining an ‘independent-minded critical engagement’ rather than an ‘uncritical commitment or loyalty to party’. When he was asked by one Derbyshire miner who had read his books, ‘Ay, I gets all that; but does thee not believe in anything, Professor lad?’, Crick responded by saying, ‘I am a democratic socialist’. Probably more tellingly, however, is the story that Crick was delighted when one interviewer called him an ‘extremist at the centre’.

The book for which Crick was most proud was his biography of George Orwell, published in 1980. It was the first major study of Orwell and was a best-seller. Crick donated royalties from the hardback version of this book to establish the George Orwell Memorial Trust. He also founded the annual Birkbeck Orwell Lecture and Orwell Prize for political writing. He could frequently be heard reciting Orwell’s famous aphorism: ‘What I have most wanted to do… is to make political writing into an art’.

Crick was an individualist. He was not a ‘team-player’; nor was he a particularly effective administrator, although he was a keen advocate for early career scholars he admired. Labour politician David Blunkett, who studied under Crick, put it well when he called Crick a ‘character…. a one-off’. During his tenure at Birkbeck, Crick promoted the highest scholarship and teaching. The Department he created in 1972 continues to flourish and to ensure that political writing is relevant and rigorous, as well as an art.