The UK’s wildlife is under pressure. A no-deal Brexit would only damage it further.

The State of Nature Report 2019 paints a bleak picture of the condition of birdlife throughout the United Kingdom – the UK’s departure from the European Union will only exacerbate this. According to the report, since 1970 the abundance and distribution of the UK’s species has declined with “no let-up in the net loss of nature” in recent years.

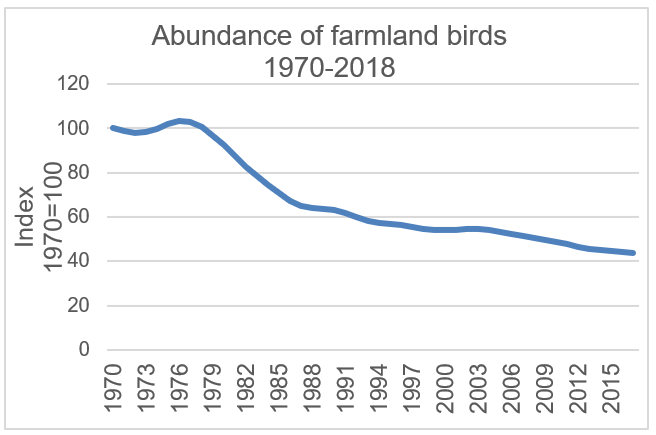

Since 1970, 41% of all UK species studied have declined and the report concluded that intensive management of agricultural land is the key contributing factor. The clearest evidence of this is the report’s findings on farmland birds – these species have been hit particularly hard by farming intensification, as shown by the 54% decrease in the Farmland Bird Indicator in this period (fig. 1).

fig 1 – British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), www.jncc.gov.uk

While there are some exceptions to the trend and recent initiatives by Defra and the EU LIFE programme have helped to stem the decline, once-common birds like lapwings and skylarks, yellowhammers and grey partridges are fading from our countryside.

Farmers – friend or foe?

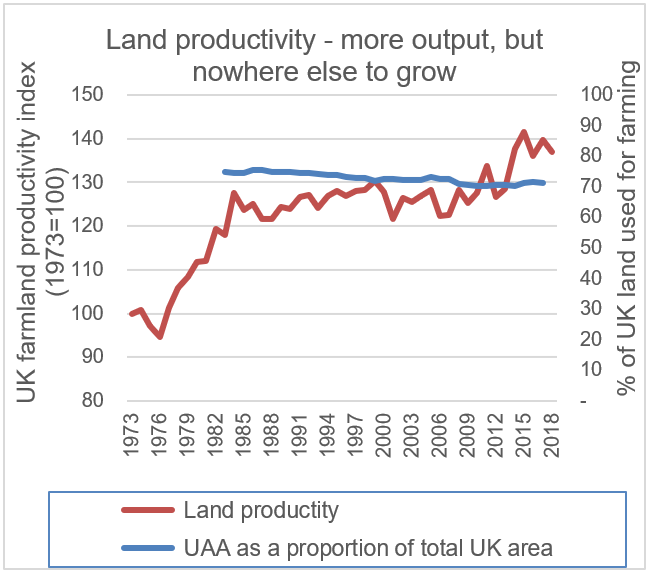

The UK’s farmers have long been seen as protectors of the countryside, but in a competitive environment the industry has resorted to increasingly intensive farming methods. The land available for farming – the Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA) – has remained around 70% of the total UK land since the 1980s (ONS) and without more land available, farmers have been forced to improve productivity wherever they can, resulting in intensification of production methods (fig. 2).

fig 2 – Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs – https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets

The productivity index for UK farmland shows an ever upward trend – new technologies play a part, but intensive land management is the key driver of these gains. For arable farming, intensive farming methods include increased pesticide use, planting multiple crops per year, the reduction in fallow years and extensions of planting seasons, while for livestock it is rotational grazing, higher livestock concentration and overfertilisation of pasture. All methods impact wildlife.

Self-sufficiency

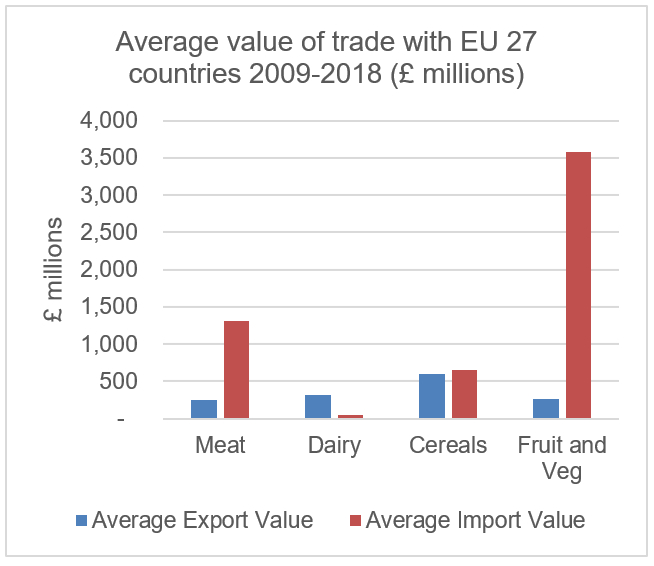

According to DEFRA, the UK is 61% self-sufficient in all foods – if, from January 1, the UK tried to survive solely on domestic production, we would run out in mid-August. Much of this production deficit is filled by goods imported from the EU – in 2018 £19.1bn of the £24.3bn deficit was with EU 27 countries.

fig 3 – Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs – https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets

While the NFU has urged the government to focus on improved food self-sufficiency following Brexit, a trade deal with the EU is crucial to secure food provision. The UK government is working towards a trade agreement, but the timeframes envisioned by the Prime Minister make a satisfactory conclusion in this area unlikely. A 2018 report focusing on potential trade agreements between the UK and the EU, produced by LSE Consulting, noted that the “agricultural sector…is often highlighted as one of the most sensitive sectors in trade negotiations” and as a result “there may be limitations on what is attainable” when it comes to any trade agreements, particularly regarding tariffs. Products could potentially be sourced from alternative trade partners, but in the short term it is likely that the UK will look to domestic farmers to fill any shortfall.

Freedom of labour is not a topic which this blog has space to address, but 8% of UK agricultural workers are EU migrants with an uncertain future in this country (House of Commons briefing paper – 7987). Farmers face the prospect a decreasing labour supply alongside a demand spike. Increased demands will have to be made on the land available for production and intensification will only escalate, exacerbating wildlife decline. Unless a trade deal can be reached with the EU the pressures from intensive farming will not ease in coming years and our countryside will be increasingly dangerous for our birds.

This blog was contributed by Henry Mummé-Young, MSc Politics, Philosophy and Economics student.

Further Information: