This post was contributed by Professor Stephen Wright, of Birkbeck’s Department of Economics, Mathematics and Statistics.

I am a Remainer. As an economist the arguments for staying in the EU seem to me pretty clearly to outweigh the arguments for leaving. As a private individual I also clearly benefit from the EU. Polish carers look after my 97-year old mother (very well). I work in multiethnic and prosperous London. I have a Serbian-Dutch prospective son-in-law. I travel quite often in Europe and like the cheap flights (who doesn’t?). And the Central and Eastern Europeans who serve my coffee at the station are so polite and efficient.

But when personal incentives coincide with intellectual arguments we need to be careful. When I criticised the pro-Brexit arguments of Patrick Minford of Cardiff University in an email he responded that my arguments were a “metro-elite rant”. He had a point.

I quote from his email (my insertions in parentheses for clarity)

The problem is the balance between skilled and unskilled (migrants) and the complete lack of control that affects large swathes of the country with pressure from large numbers of

unskilled (migrant) workers: effects on housing, hospitals and schools, not to speak of wages (though evidence here is hard to get). Look, if the elite will not compensate these guys they must expect a political explosion which they have now got.

I reiterate: I am, and remain, a Remainer. But Patrick does have a point. If we Remainers do not take these arguments seriously, and – ideally – try to persuade policymakers to do something about these problems – there is a very serious risk that the Brexiteers will win the vote.

One chart, from the LSE’s John Van Reenen and co-authors (See Footnote 1) tells most of the story.

Source: CEP analysis of Labour Force Survey. Wadsworth et al. (2016: 7). Notes: Median wage is deflated by the CPI.

And, as with so many charts, the story that it tells depends on your perspective. From the perspective of a UK-born worker at the lower end of the distribution what they can see, without any advice from expert economists, is that the real value of their wages has fallen almost continuously (by around 10% for someone on the median wage –See Footnote 2) since the peak before the crisis. They can also see, without the aid of the chart (who cannot?) that at the same time the share of EU migrants in the population has risen steadily. And, inevitably they draw a link between the two phenomena.

Van Reenen and co-authors point out (quite correctly) that the share of EU migrants had been rising well before real wages started falling, indeed, as the chart shows, during a period in which real wages were still rising steadily. They also point to a range of evidence showing a lack of a link between EU migration and UK-born wages or unemployment. And they reiterate the arguments that Brexit would lower GDP via reduced trade, job losses, and higher prices of imported goods.

So should we just dismiss the arguments about EU migration as xenophobic scaremongering? Well of course a lot of it is pretty unpleasant, and often verges on the xenophobic. But that does not mean we can simply dismiss the arguments out of hand.

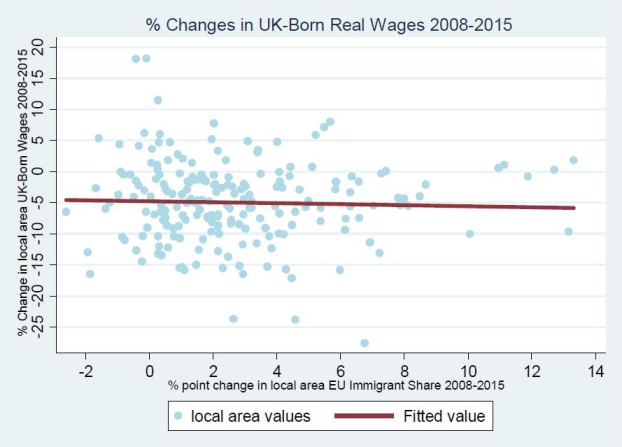

Wages and unemployment, first of all. Is the case against a link proven by the lack of a correlation? Here is one of the charts that Van Reenen and co-authors use to make their case.

Source: CEP analysis of Labour Force Survey. Wadsworth et al. (2016: 10).

Notes: Each dot represents a UK local authority. The solid line is the predicted ‘best fit’ from a regression of local authority percentage change in wages on the local authority change in share of EU immigrants. These are weighted by the sample population in each area. Slope of this line is -0.08 with standard error of 0.15, statistically insignificantly different from zero.

This shows that there has been essentially a zero correlation between changes in real wages in any given local authority and the increase in EU migration in the same local authority. Case proven, it seems.

But pause, just for a moment. Basic statistics courses teach that “correlation need not imply causation”. But there is a subtler version: lack of correlation need not imply lack of causation. Here’s a simple argument (which is easy to substantiate with a couple of lines of algebra).

Suppose that real wages at a regional level tend to be stronger (which in recent years typically means to fall less rapidly than the average – look at the y-axis on the chart) where the regional economy is stronger. And suppose that EU migrants know this. Where will they tend to move to in the UK? Well, to the more prosperous regions, of course. Now suppose that the Remain arguments are correct, and more EU migrants do not have any effect on wages. If that was the case, then we should expect to see a positive correlation in the scatter diagram, but we do not. Whereas if EU migrants do depress wages, this would dampen the positive relationship and possibly result in no correlation at all. Which is what we see in the chart.

Now Van Reenen and his co-authors are all excellent econometricians so they all know this kind of argument perfectly well. Which makes their arguments all the more disingenuous. I’m not claiming that this proves there has been a serious impact on wages. There has been plenty of more sophisticated research which suggests it is hard to find an impact either way (and which Minford acknowledges in the quote above). But that does not in itself prove the argument wrong.

What about hospitals and schools? Well here the Remain argument is on the face of it much stronger. Van Reenen and others have shown that EU migrants are pretty clearly net contributors to the public purse. But the only problem with this argument to the UK-born worker is that there is no direct observable impact of these higher tax receipts on hospitals and schools. We do not have labels on CT scanners or smart whiteboards saying “these facilities were paid for using the extra tax receipts from EU migrants paypackets”. All they can see is the queues and the letters assigning their child to a school two bus rides away.

And finally, of course, housing. Well here of course, all the economists agree. And the policymakers. Everyone agrees. Absolutely everyone. We must build more houses.

But we don’t. Or at least not enough. Nor have we, for decades. As a result, UK households spend more on housing, per square metre of residential land, then any other European country except Luxembourg (See Footnote 3).

Does EU migration make things worse? Well of course it must do. (Even Nigel Farage can be right once in a while.) The CEP paper documents that the number of EU migrants in the UK rose by 2.4 million between 1995 and 2015. That accounts for roughly one third of the total growth of population in the UK over that period. And meanwhile, as Bank of England governor Mark Carney pointed out back in 2014, the UK builds half as many houses each year as Canada despite having twice the population.

No one disagrees that this is crazy. Yet neither the government nor the opposition have made any move to do anything serious about it. Despite the fact that bringing down the cost of housing could be the most effective way (and possibly the only effective way) of raising living standards for UK workers in the medium to long term.

But don’t get me started on housing. It is a serious, a very serious problem, that goes way beyond arguments about Brexit. But, I reiterate, EU migration must be making it worse.

Does all of this mean that I think we should stop EU migration? (Even if we could, which is of course debatable, even post-Brexit). It does not. Despite the fact that, as I noted at the start, my personal interests coincide with my professional judgement, I stick with that judgement. The EU brings benefits. EU migrants bring benefits. To me, and people like me, especially. To the economy on average, almost certainly. But not to everyone.

Pro-Remain policymakers need to start thinking fast about acknowledging this, and how to offer something to the poor and dispossessed of this country to compensate them explicitly for the costs of EU migration. This would not be impossible: remember the last-ditch crossparty promises before the Scottish vote? Maybe these made a difference, maybe they didn’t. But it is worth a try. Very soon it will be too late.

Find out more

Courses at the Department of Economics, Mathematics and Statistics

Images sourced from Wadsworth, J., Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G., Van Reenen, J., and Vaitilingam, R. (2016) ‘Brexit and the Impact of Immigration on the UK’. CEP BREXIT ANALYSIS NO. 5. Available online, last retrieved 13 June 2016.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Birkbeck

Footnotes

- “Brexit and the Impact of Immigration on the UK”, Jonathan Wadsworth, Swati Dhingra, Gianmarco Ottaviano and John Van Reenen, CEP Brexit Analysis No. 5.

- The CEP document shows that the fall for those on the 10th decile has been somewhat larger, and started

earlier. - De La Porte Simonsen, L and Wright, S (2016) “Residential Land Supply in 27 EU Countries: Pigovian Controls or Nimbyism?, paper presented to Birkbeck Centre for Applied Macroeconomics Annual Workshop, May 2016.

Out out out out. Also most the British public don’t agree with this as polls are in favour of Brexit. Too much scare mongering and not enough reasons for staying in the EU.

Also weren’t economists wrong about joining the ERM? They were also wrong about the financial crisis-and they went even further by encouraging governments to de regulate the banks which caused the global recession.

If some economists have been wrong before, it doesn’t follow that all economists or this economist cannot ever be right. Scientists, historians, all get things wrong sometimes. I think you would probably agree that those who have studied economics are on average more likely to make correct economic predictions than those who have not. If we shouldn’t let experts guide our policy-making, then who else should we ask?

I think you are missing the main point of this article. It is not to convince you to vote Remain. The title says all you need to know: “If we want the UK-born poor to vote Remain we need to take their grievances seriously”

A very balanced and accurate take on a complex and heavily debated issue. I wonder though if it is as you say, the Remain camps’ responsibility to offer something to the poor “to compensate them explicitly for the costs of EU migration.” As a Remainer and economics student myself, I whole heartedly agree that issues such as housing and influx unskilled labour should be addressed by the current and opposition governments but for the sake of the upcoming referendum I don’t believe that it’s the remain campaign’s responsibility to solve these problems in order for those who are socially excluded to support the ideas of a United Kingdom with stroger EU ties. Again, I whole heartedly agree with the ideas that you outlined but I feel that the pressure on Remain to constantly refute the claims of an ‘out of control Brussels’ and a ‘tidal wave of Turkish immigrants coming to steal our jobs’ just as ridiculous as claims of ‘immigrants coming over here and drinking our water’ during the hose pipe ban not so long ago.

Sincerely,

Josh Tal

This is a very good entry, only it comes way too late with only week to go before the referendum.

Furthermore, the post stops short of offering any concrete solutions. It is clear that the Leave campaign intends to alleviate congestion externalities through limiting demand. What are the options for the Remain campaign? Currently, EU migrants are just paying their way. Would it still be the case if the capacity of public services were to be expanded? It could well be the case that the incremental cost of capacity expansion is significantly higher than the average cost of use of existing services. What are the solutions for housing? Another credit boom or relaxing planning regulations?

I agree it’s almost certainly too late now.

I didn’t put any concrete proposals because the piece was already too long!

For the record, here are some ideas I put to a Labour Party insider a couple of weeks ago. They are all about supply.

1. Promise legislation along the lines of the German law that requires a given amount of land to be released every year for new buildings. Ironically having released so much land historically they are now trying to reduce it. Publicity-wise, “if the Germans can do it why can’t we?”.

2. Given that the situation could rationally be characterised as a crisis, I think I’d be prepared to suggest that to kick-start the process, the government should be prepared to engage in significant compulsory purchases of (non-Green Belt) farmland, just as it would for a major infrastructure project, to liberate say a decade or two’s worth of new land. This would then be sold on to a combination of developers and housing associations (the latter as a sop to Labour sensibilities) (Green Belt is, by the way, only 13% of the land in the UK so there is plenty of land to choose from)

3. Reverse this relatively recent change: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/property/property-market/7826533/Garden-grabbing-the-rules-for-homeowners.html

4. As a short-term measure, follow the Swedes and allow small new structures in gardens (http://qz.com/311393/a-new-planning-rule-in-sweden-inspired-these-tiny-beautiful-structures/). “If the Swedes can do it so can we”, and allow them to be rented out.

5. Make it explicit that it is a target of policy to stop further house price growth. By doing so you would signal to housebuilders that the only way to make money is by building houses, rather than simply waiting for capital gains. The same would apply to absentee Chinese owners with empty flats. It’s a subtler point, but “ take away the profit for speculators” might be an OK slogan.

History has strange ways of playing mind games. The lacklustre European Free Trade Area project found Britain knocking on the European Economic Community’s door in the 1960s. French President Charles de Gaulle said ‘non’ twice. The UK has been publicly accused of a chronic deficiency in the balance of payments, and relying too much on cheap food imports from the Commonwealth. The General wrote in his memoirs that the British wished to paralyse the Community from within, having failed to prevent its birth. It is said that he also feared English becoming the lingua franca of the Community. He was defeated in a referendum on governmental reforms and resigned in 1969, dying a year later. The UK eventually became an EEC member on 1 January 1973. English is now the common language of the European Union. The UK unemployment rate floats at about the same level as before the EU’s Eastern enlargement in 2004, an action strongly encouraged by Westminster.

Thousands of years ago forces of nature destroyed Albion’s land bridge with the rest of the continent. It is now a tsunami of political discontent threatening to sever UK’s ties with the world’s largest single market. Professor Wright claims that the economic argument for staying in the EU is clear; one can hardly disagree with that. As Chris Giles in the Financial Times pointed out, in a pivotal moment Britain’s economists speak with a single voice. This is a rare occurrence. A few exceptions seem to be plagued by magical thinking. Economics students learn about the importance of ceteris paribus and how not to misuse it. If the UK exits the EU, other EU members and the rest of the world will not sit still. There are competing interests across the Channel and beyond. Their collective trade firepower is bigger and they will act. Nations do not have friends for eternity. The UK can only benefit in the long term if the EU dissolved and other big players were mired in perennial economic misery. Witnessing both of these outcomes is unlikely. Even then, desperation could lead to the return of ugliness.

The Brexit side has yet to inspire confidence regarding strategic planning for the next generations. They perfectly understand that. In a mathematically-challenged but cleverly designed campaign, their argument is that Britain is important and will assert its rightful position in the world. When you are poor, cheering about improving your prospects is more desirable than assuming the foetal position when MPs and academics point the finger. Struggling families cannot connect with sermons by foreign politicians and international organisations. Vote Leave has pathos. With Labour engaged in soul-searching about the political centre, Conservatives amidst another civil war and Liberal Democrats decimated, there is nothing exciting in the Remain camp. Plus, the EU’s handling of the Eurozone and refugee crises, although both haunted by hyperinflation fixations and poll-based politics, did not exactly help.

The public is often wrong and referendums are about more than the question asked. Rich or poor, being at odds with a government’s domestic policies, regardless if these are correct, makes it difficult to support it. Few can think with a cool head. Only tangible solutions tip the scales. But it is debatable if, for example, a last-ditch promise to fix the housing crisis before the next general election would help. Vote Leave would still be able to claim that a portion of public money would end up helping migrants anyway. Objecting to ‘British homes for British people’ would be suicidal for the vast majority of MPs. It is British people voting for them. What if a number of studies found that European migrants are net contributors, adding to the public purse for British people in need? It would be inconsequential. By the power of magical thinking, if migrants did not exist at all there would be more empty houses for the natives. Imagine there’s no shortage, it’s easy if we try. People can connect with that. There are no equations involved. But what about the costs of building new houses and the hole in public finances? Well, obviously increased trade with other countries or planets will fix these, experts know nothing. There is an answer for every question because populism is not bound by rational constraints. A decade ago American comedian Stephen Colbert introduced the concept of truthiness: if it feels right for one, it must be true for everyone. The Atlantic Ocean seems to be leaking.

Young people should be able to get on the property ladder, class sizes should be small and NHS waiting times should be kept to a minimum. Both natives and migrants agree. But the latter are often convenient scapegoats for systematic failures of domestic policies. Be it for love or commerce, migration is a fact of life and the genetic makeup of these islands is a testament to that. Preventing the fear of the Other from taking control of the public sphere requires creative thinking. New member states rely on EU funding to modernize their infrastructure and improve their standards of living. They are also interested in keeping their brightest within their borders, as brain drain impedes their efforts. A simple mechanism could provide EU funding to the UK and others receiving a high number of migrants from specific countries. For example, if the number of migrants from EU member state X crosses a certain threshold, the UK could receive a ‘mobility rebate’ from the EU budget and country X’s share would be reduced. It is a simple concept: fund Britain for dealing with the increased load by X’s nationals. It is also a fair concept because it only targets the source; not all EU members send high numbers of migrants. The exact amount could be calculated by taking into account the ratio of country X’s migrants to its total population. Funds would then be directed to UK regions in need. This solution has the benefit of not interfering with the Freedom of Movement principle. It also forces countries of origin to better utilize EU assistance and keep their citizens happy.

Britain has a pull factor. There are benefits and disadvantages to that. Many find the net result positive. Others remain unconvinced, conflating personal experience with macroeconomic reality. Misguided they may be, belittled they should be not. In any case, it is too late to restore institutional confidence when polls indicate that Britain could be sleepwalking towards an EU exit. Millions of poor families want to vent fury at unelected Brussels officials and any elements of irony completely evade them. They are certain Britain can do better by throwing off the EU shackles. But there are no certainties in life. Nobody thought that in 2016 an MP would be murdered while performing her duties. Another wound, this time a self-inflicted one, at least in the short to medium term, is the last thing the British economy now needs.

I don’t think this is a wholly balanced blog, but I do whole-heartedly agree that we must be doing more to address inequality and also the far too widespread perceptions among lower earners that immigration is the cause of, or exacerbates, their woes. I also agree that BREXIT is most unlikely to reduce immigration levels- which is why Kayley’s ‘Out out out’ chant is largely irrelevant to the EU debate. But I do not see why such eminent economists as John van Reenan et al , are described as ‘disingenuous’. The explanation that the blog’s author gives for the lack of correlation of immigration and wages is but one example of the ubiquitous presence of ‘endogeneity’, and we are talking only about damping rather than reduction of wages so the effect would be an upper truncation resulting in a concave curve at the upper end rather than a complete linear tilt, and this does not seem borne out by the chart. More importantly, as the blog’s author says, Dustmann, Nickell, John van Reenan, Wadsworth et al are all excellent econometricians. So they DO address endogeneity elsewhere in more technical papers e.g. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Documents/workingpapers/2015/swp574.pdf. And there are also at least four large natural experiments of large movements of populations to draw on to show that even in the absence of endogeneity the impacts of immigration on wages and unemplyment are ‘surprisingly’ small to non-existant. It is simply unfair to call such well-respected researchers ‘disingenuous’. The chart the blog’s author chooses to ‘critique’ is not Reenan’s or Wadsworth’s actual ‘proof’ but merely a useful way of illustrating the lack of an association to a non-technical audience in a non-technical brief- something to be encouraged!

In anycase, it is unbalanced to emphasise just one ‘confounder’, i.e. plausible alternative explanation, to suggest there might after all be a hidden negative effect of immigration. There are just as many possible confounders for hidden positive effects. For example, dynamics effects are notoriously very difficult to capture, but a lot of evidence suggests that economies are more like engines rather than cakes to be shared-out. That is, more fuel to an engine increases the power output so that all the ‘passengers’ move along at a faster rate- so we might all, including lower earners, be better off than without immigration. We can’t tell without a good way of capturing the dynamics and a strong counterfactual. But as there is strong evidence that immigration raises the average wage, we should be able to compensate lower workers anyway.

The large majority view of economists is that the weight of evidence from a host of studies is that immigration has only small to non-existent direct effects but it does dramatically lower debt/GDP ratio- as is explained here: http://www.niesr.ac.uk/blog/migration-and-public-finances-long-run-obrs-fiscal-sustainability-report#.V2QsTDU75Fk

It is my view that overwhelmingly the cause of any strain on services is not immigration, NHS wating times are actually less where there is higher immigration, but is due to an unnecesary and ideologically driven ‘austerity’. Something I left the Treasury early because of.For housing this is combined with an appallingly low rate of house building, neglect of investment in and the selling-off of socially/collectively funded housing and quite ludicrous planning restrictions.

I do think we should be calling other economists disingenous or letting government’s off the hook by trying to suggest against the majority of economists in the field to that immigration is an economic problem, it might be a social problem, but that’s only going to be improved by insisting on evidence based arguments, or as the evidence also suggests, more immigration!

On a more consensual note, I again completely agree with the headline of the blog: “If we want the UK-born poor to vote Remain we need to take their grievances seriously”

Many thanks for all the comments. As Arina says: too late to make a difference now. We shall soon see. Time then to discuss how best to deal with whatever decision is made.

Stephen

Kayley, just imagine we decided to do a referendum on “shall we give 1 million pounds to each household in the country”. You will get a clear YES, and then can claim that “democracy has not been respected” if the money does not magically appear…

nice post

Many thanks for all the comments. Arina says: too late to make a difference now. We shall soon see. Time then to discuss how best to deal with whatever decision is made.

Many thanks for all the comments. moment says: too late to make a difference now. We shall soon see. Time then to discuss how best to deal with whatever decision is made.

Many thanks for all the comments. moment says: too late to make a difference now. We shall soon see. Time then to discuss how best to deal with whatever decision is made. so the