This post was written by Professor Eric Kaufmann from Birkbeck’s Department of Politics. It was originally published on the LSE British Politics and Policy blog

As the final votes are counted, pundits and pollsters sit stunned as Donald J. Trump gets set to enter the White House. For anyone in Britain, there is a sharp tang of déjà vu in the air: this feels like the morning after the Brexit vote all over again. Eric Kaufmann explains that, as with Brexit, there’s little evidence that the vote had much to do with personal economic circumstances.

For months, commentators have flocked to diagnose the ills that have supposedly propelled Trump’s support, from the Republican primaries until now. As in Britain, many have settled on a ‘left behind’ narrative – that it is the poor, white, working-class losers from globalization that have put Trump over the top. Only a few clairvoyants – Michael Lind, Jonathan Haidt – have seen through the stereotypes.

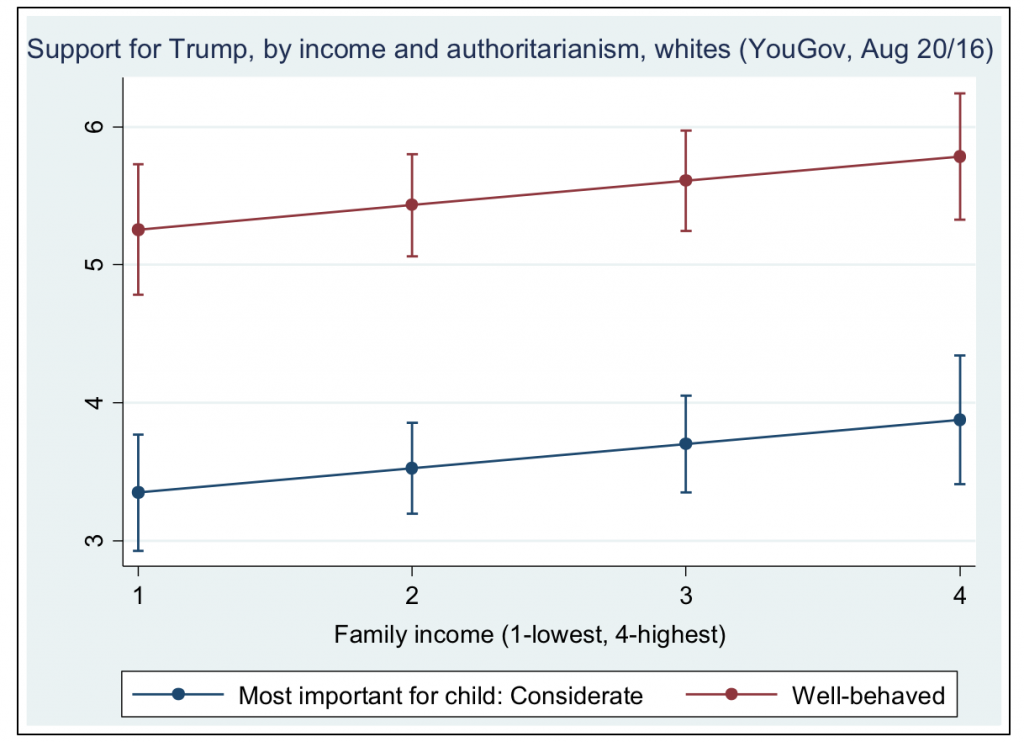

But, as in Britain, there’s precious little evidence this vote had much to do with personal economic circumstances. Let’s look at Trump voting among white Americans from a Birkbeck College/Policy Exchange/YouGov survey I commissioned in late August. Look at the horizontal axis running along the bottom of figure 1. In the graph I have controlled for age, education and gender, with errors clustered on states. The average white American support for Trump on a 0-10 scale in the survey is 4.29.

You can see the two Trump support lines are higher among those at the highest end of the income scale (4) than the lowest (1). This is not, however, statistically significant. What is significant is the gap between the red and blue lines. A full two points in Trump support around a mean of 4.29. This huge spread reflects the difference between two groups of people giving different answers to a highly innocuous question: ‘Is it more important for a child to be considerate or well-mannered?’ The answers sound almost identical, but social psychologists know that ‘considerate’ taps other-directed emotions while ‘well-mannered’ is about respect for authority.

People’s answer to this question matters for Trump support because it taps into a cultural worldview sometimes known as Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA). Rather than RWA, which is a loaded term, I would prefer to characterise this as the difference between those who prefer order and those who seek novelty. Social psychologist Karen Stenner presciently wrote that diversity and difference tends to alarm right-wing authoritarians, who seek order and stability. This, and not class, is what cuts the electoral pie in many western countries these days. Income and material circumstances, as a recent review of research on immigration attitudes suggests, is not especially important for understanding right-wing populism.

Figure 1.

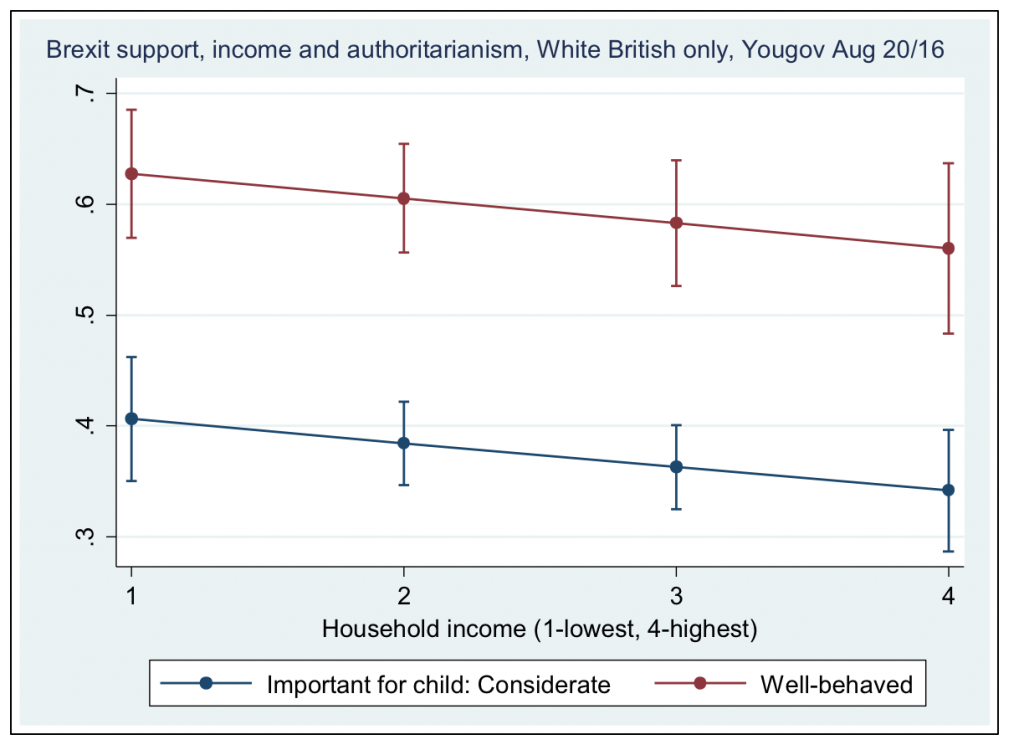

Now look at the same graph in figure 2 with exactly the same questions and controls, fielded on the same day, in Britain. The only difference is that we are substituting people’s reported Brexit vote for Trump support. This time the income slope runs the other way, with poorer White British respondents more likely to be Brexiteers than the wealthy. But income is, once again, not statistically significant. What counts is the same chasm between people who answered that it was important for children to be well-mannered or considerate. In the case of Brexit vote among White Britons, this represents a 25-point difference around a mean of 45.8 per cent (the survey undersamples Brexiteers but this does not affect this kind of analysis). When it comes to Brexit or Trump, think successful plumber, not starving artist or temporary lecturer.

Figure 2.

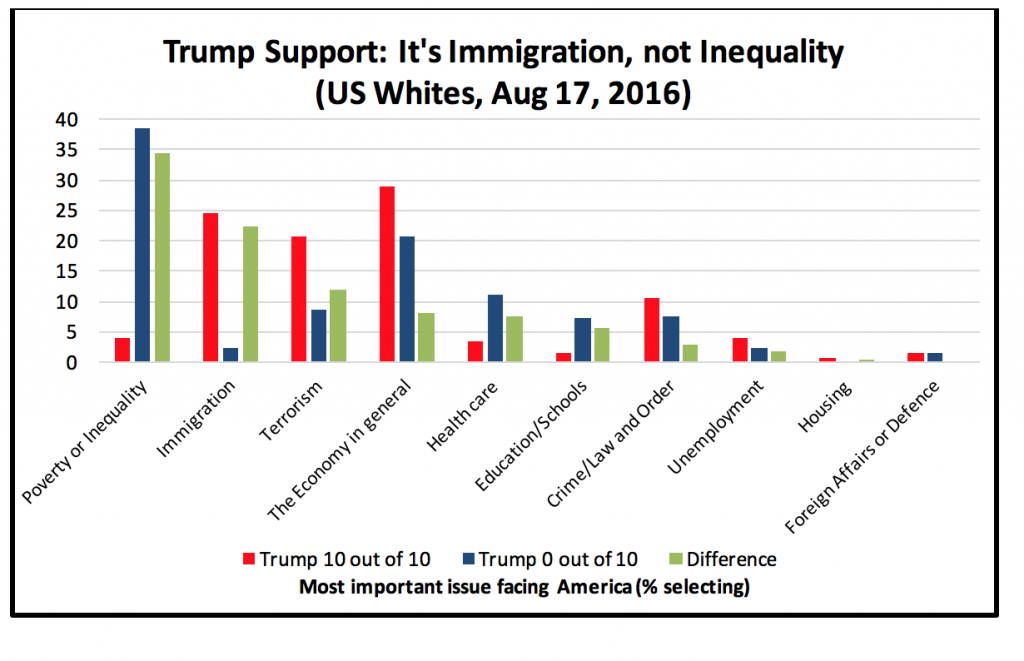

Some might say that even though these populist voters aren’t poor, they really, actually, surely, naturally, are concerned about their economic welfare. Well, let’s take a look at the top concerns of Trump voters in figure 3. I’ve plotted the issues where there are the biggest differences between Trump supporters and detractors on the left-hand side. We can start with inequality. Is this REALLY the driving force behind the Trump vote – all that talk about unemployment, opioid addiction and suicide? Hardly. Nearly 40 per cent of those who gave Trump 0 out of 10 (blue bar) said inequality was the #1 issue facing America. Among folks rating the Donald 10 out of 10, only 4 per cent agreed. That’s a tenfold difference. Now look at immigration: top issue for 25 per cent of white Trump backers but hardly even registering among Trump detractors. Compared to immigration, even the gap between those concerned about terrorism, around 2:1, is not very striking.

Figure 3.

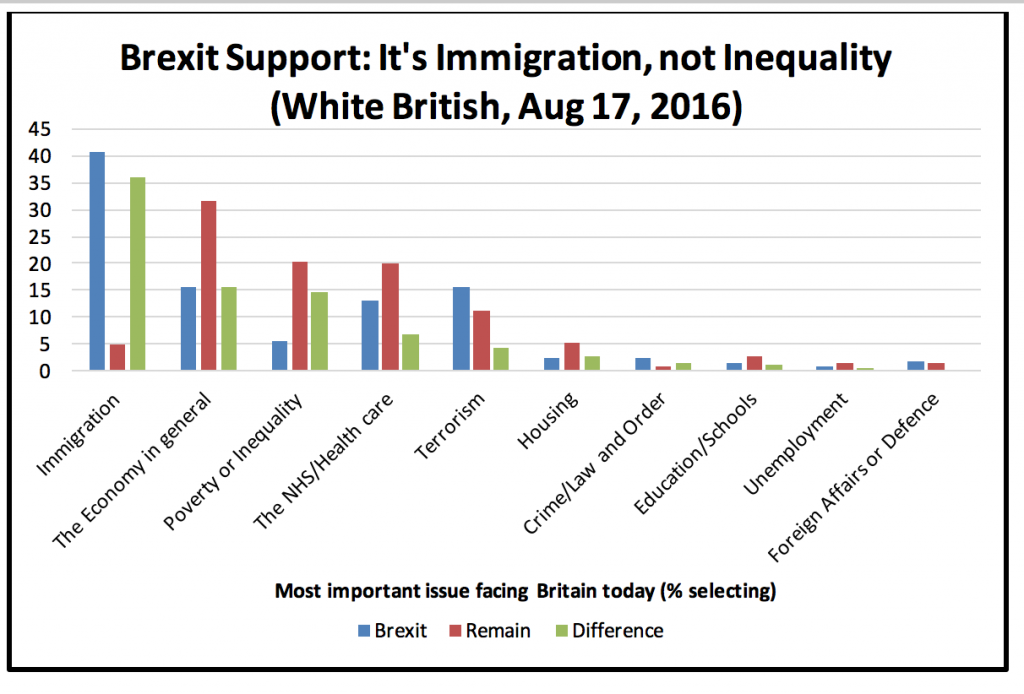

For Brexit vote, shown in figure 4, the story is much the same, with a few wrinkles. The gap on immigration and inequality is enormous. The one difference is on ‘the economy in general,’ which Trump supporters worry about more than Brexiteers. This could be because in the graph above I am comparing extreme Trump backers with extreme detractors whereas the Brexit-Bremain numbers include all voters. Still, what jumps out is how much more important immigration is for populist voters than inequality.

For Brexit vote, shown in figure 4, the story is much the same, with a few wrinkles. The gap on immigration and inequality is enormous. The one difference is on ‘the economy in general,’ which Trump supporters worry about more than Brexiteers. This could be because in the graph above I am comparing extreme Trump backers with extreme detractors whereas the Brexit-Bremain numbers include all voters. Still, what jumps out is how much more important immigration is for populist voters than inequality.

Figure 4.

Why is Trump, Brexit, Höfer, Le Pen and Wilders happening now? Immigration and ethnic change. This is unsettling that portion of the white electorate that prefers cultural order over change.

Why is Trump, Brexit, Höfer, Le Pen and Wilders happening now? Immigration and ethnic change. This is unsettling that portion of the white electorate that prefers cultural order over change.

The US was about 90 percent white in 1960, is 63 percent white today and over half of American babies are now from ethnic minorities. Most white Americans already think they are in the minority, and many are beginning to vote in a more ethnopolitical way. The last time the share of foreign born in America reached current levels, immigration restrictionist sentiment was off the charts and the Ku Klux Klan had 6 million members – mainly in northern states concerned about Catholic immigration.

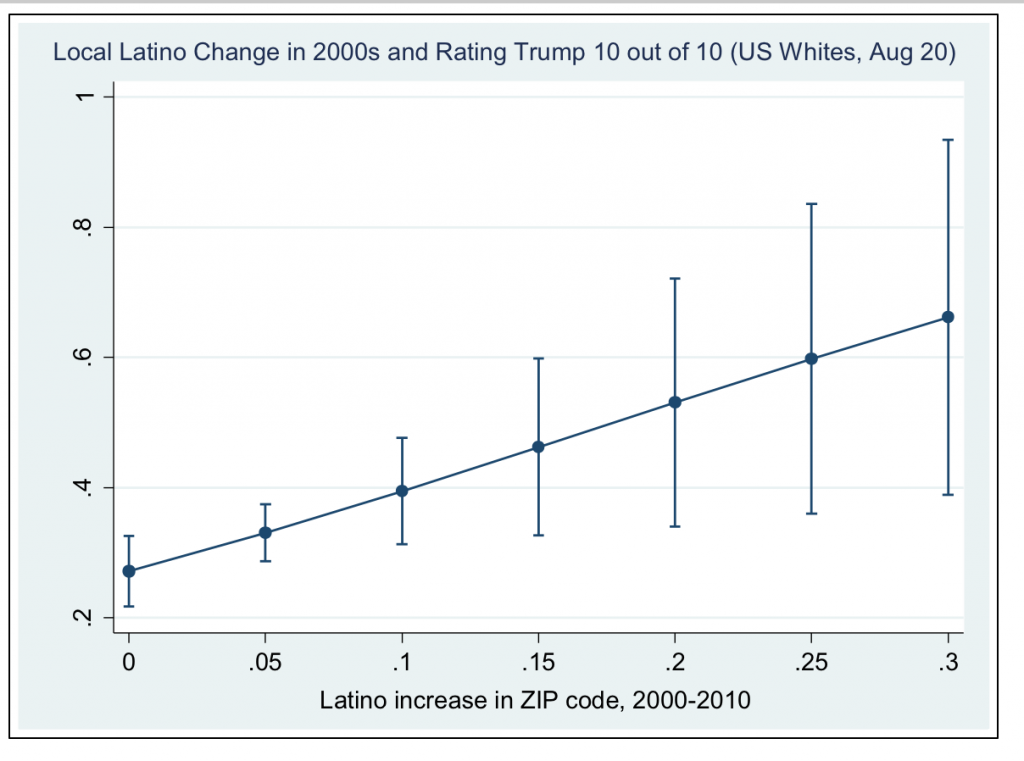

Ethnic change can happen nationally or locally, and it matters in both Britain and America. Figure 5, which includes a series of demographic and area controls, looks at the rate of Latino increase in a white American survey respondent’s ZIP code (average population around 30,000 in this data). The share of white Americans rating Trump 10 out of 10 rises from just over 25 percent in locales with no ethnic change to almost 70 percent in places with a 30-point increase in Latino population.

The town of Arcadia in Wisconsin – fittingly a state that has flipped to Trump – profiled in a recent Wall Street Journal article, shows what can happen. Thomas Vicino has chronicled the phenomenon in other towns, such as Farmer’s Branch, Texas or Carpentersville, Illinois. There are very few ZIP codes that have seen change on this scale, hence the small sample and wide error bars toward the right. Still, this confirms what virtually all the academic research shows: rapid ethnic change leads to an increase in anti-immigration sentiment and populism, even if this subsequently fades. The news also spreads and can shape the wider climate of public opinion, even in places untouched by immigration.

Figure 5.

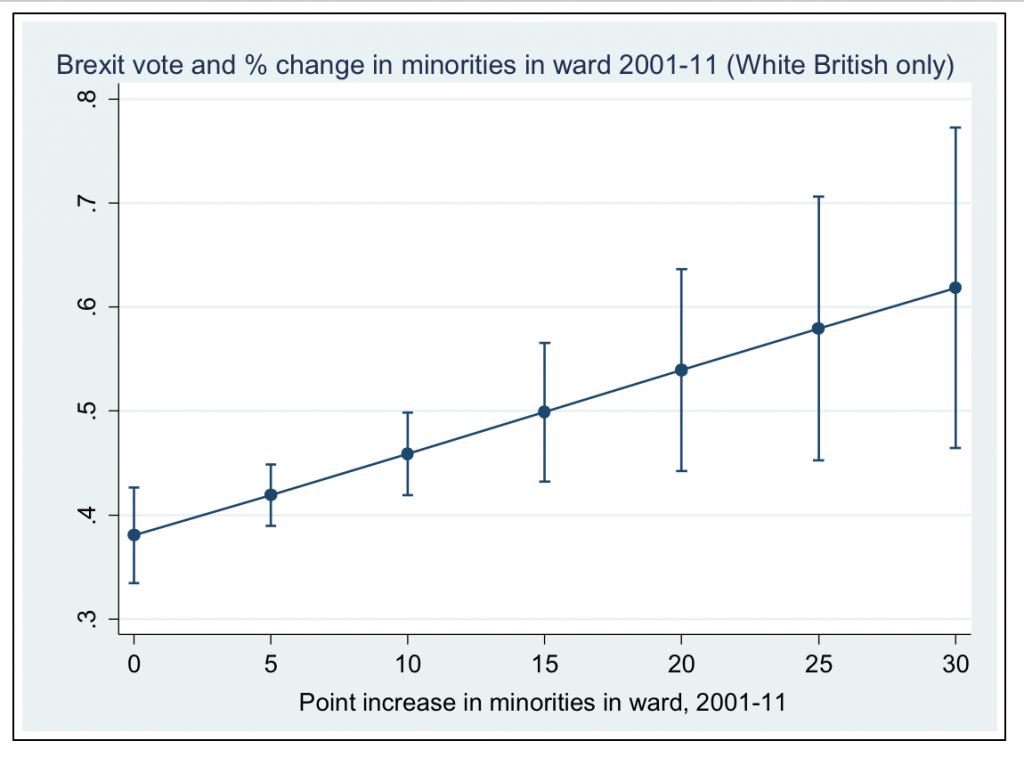

Now let’s look in figure 6 at Brexit, and how White British voters in wards with fast East European growth in the 2000s voted. With similar controls, it’s the same story: when we control for the level of minorities in a ward, local ethnic change is linked with a much higher rate of Brexit voting. From under 40 percent in places with no ethnic change to over 60 percent voting Brexit in the fastest changing areas. Think Boston in Lincolnshire, which had the strongest Brexit vote in the country and where the share of East Europeans jumped from essentially zero in 2001 to the highest in the country by 2011.

Now let’s look in figure 6 at Brexit, and how White British voters in wards with fast East European growth in the 2000s voted. With similar controls, it’s the same story: when we control for the level of minorities in a ward, local ethnic change is linked with a much higher rate of Brexit voting. From under 40 percent in places with no ethnic change to over 60 percent voting Brexit in the fastest changing areas. Think Boston in Lincolnshire, which had the strongest Brexit vote in the country and where the share of East Europeans jumped from essentially zero in 2001 to the highest in the country by 2011.

Figure 6.

The Trump and Brexit votes are the opening shots which define a new political era in which the values divide between voters – especially among whites – is the main axis of politics. In a period of rapid ethnic change, this cleavage separates those who prefer cultural continuity and order from novelty-seekers open to diversity. Policymakers and pundits should face this instead of imagining that old remedies – schools, hospitals, jobs – will put the populist genie back in the bottle.