Last week UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the scrapping and watering down of several key climate targets. Academics Dr Pam Yeow, Reader in Management and Dr Becky Briant, Reader in Quaternary Science, share their thoughts in a blog.

We read with disappointment and concern the latest announcement from the UK Prime Minister, of the intentions to roll back climate positive strategies and priorities until 2035. This is unfortunate for both scientific and economic reasons.

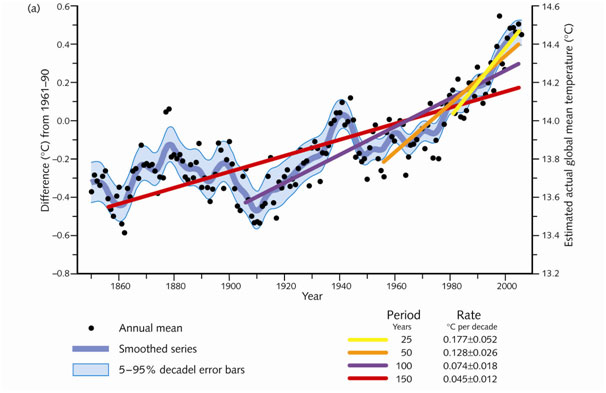

Over the past decade it has become increasingly clear that the impacts from climate change are being experienced at lower levels of change than previously projected. Most climate mitigation policies propose to keep warming below 2 degrees centigrade beyond pre-industrial averages and yet at current levels of warming (only 1.2 degrees), we are already seeing extreme weather events on an annual basis, from the wildfires that started in Canada in June and are still alight, to extreme heatwaves and wildfires in southern Europe and the Middle East this July, to significant hurricane disruption in the US in August, to multiple floods and landslides just this month, for example in Libya and Hong Kong. The facts of climate change don’t stop being facts when we choose to ignore them.

Similar thresholds are being crossed in all areas of environmental degradation, with the reporting this month that six of the nine ‘planetary boundaries’ identified back in 2009 as ‘guard-rails’ beyond which humanity should not go if we want to live on a habitable planet have been crossed, meaning that Earth is now significantly outside of the safe operating space for humanity. For example, the disposability of single-use plastics, once hailed as a symbol of modernity with its low cost, convenience and durability has resulted in significant social and environmental concerns such as low recyclability rates and large volumes entering landfills and marine-based environments, leading to health concerns. Action is needed across the board to ensure our planet remains habitable; also to avoid the extreme costs associated with both clearing up and rebuilding after extreme weather events and taking care of those whose health has been damaged by the degradation of our environment. The issues involved are so intertwined that action on one will increase the likelihood of success on another.

Globally, the only way to avoid the worst climate change scenarios is for all countries in the world to reach net zero emissions by 2050 and then to move to negative emissions. Reaching net zero by 2050 requires such a steep emissions reduction that emissions need to halve by 2030 in order to reach it, in what the United Nations (UN) have called ‘the decisive decade’. The UK’s previous policy commitments were barely able to bring the UK economy to net zero by 2050 anyway, but last week’s announcements move us even further away from success. Furthermore, given that the requirement is global and many countries are moving much more slowly to action, the UK has an ethical obligation as an early and substantial historical emitter to double down on climate action, not roll back.

These announcements are particularly troubling because we had not so long ago led the field in taking environmental action, with the first statutory commitments in the 2008 Climate Change Act and a raft of strategies and policies over the last decade that addressed many, if not all, of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in addition to straight emission reduction commitments. For single use plastic waste for example, in 2017, the UN adopted an additional resolution in relation to SDG 14 (Life Below Water) that included an agreement to implement long-term and robust strategies to reduce the use of single-use plastics and microplastics (UN General Assembly, 2017). In 2022, a UN resolution was drafted to end plastics pollution. Meanwhile, the UK, alongside the EU, introduced similar measures around single-use plastics, including a 5p carrier bag charge which increased to 10p in 2021, and a ban on single use plastic items that included plates, trays, bowls, cutlery and food containers from October 2023. A plastic packaging tax generated £276 million in the first year of introduction (2023) and there were other consultations that took place, regarding the introduction of deposit return schemes in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

More industries than ever have now come aboard and engaged with the sustainability agenda, giving hope that concerted action might be possible. Many voluntary initiatives were introduced and taken on by organisations like the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation which introduced concepts like the plastic circular economy and the encouragement of a reduction alongside recycling and reusing. The UK Plastics Pact have some of the world’s largest packaging producers, brands, retailers and NGOs signed up to a shared vision with targets of eliminating ‘problem’ plastics, increase the use of reusable or recyclable plastics and achieving 30% average recycled plastic in items (WRAP, 2022). Similarly, many companies have signed up to the UN’s ‘Race to Zero’.

The UK government needs to recognise that environmental action and economic health are not mutually exclusive. We need a systemic framework of engagement, involving global, national and local groups, which occurs in the context of cross-party consensus and does not change. In addition to the environmental harm caused, chopping and changing government policy kills jobs and future investment. After the shock announcement this week, the car industry reacted furiously as they had agreed as an industry to work towards more environmentally friendly automobiles, contributing to an infrastructure of electric charging network as well as better performing fully electric vehicles. Other global leaders have also reacted with dismay at this turnaround and have urged the UK government to reconsider.

We are clear that negative climate changes and environmental degradation are already taking place. It is imperative that governments work in tandem with industry, local governments and citizens towards priorities and strategies that help our planet thrive. We urge the UK government to take the lead again in creating opportunities for a greener planet and healthier and happier citizens.

Further information

I

I