If your new year’s resolution was to finally write that novel, Toby Litt, writer and senior lecturer in creative writing in Birkbeck’s Department of English and Humanities has some advice for you. This article was originally published on Toby’s personal blog.

If your new year’s resolution was to finally write that novel, Toby Litt, writer and senior lecturer in creative writing in Birkbeck’s Department of English and Humanities has some advice for you. This article was originally published on Toby’s personal blog.

9 things you need to write a novel

The first thing you need to write a novel is… Time.

The first thing you need to write a novel is… Time.

The second thing you need to write a novel is… More Time.

And the third thing you need to write a novel is… Even More Time.

This perhaps seems a bit obvious. But let me explain.

Time, More Time and Even More Time are all necessary.

I’ve divided Time up into three because you need Time for different things.

The first lot of Time is, as I’m sure you’ve guessed, Time to write. Time to sit at the desk with words coming out of you.

The second lot of time, More Time, is… Time not to write. Time to do stuff which doesn’t seem to be writing but which, in the end, turns out to have been writing all along. To the uninitiated, this may appear to be window shopping or people-watching, taking a nice long nap, or tracking down YouTube clips of something you once saw on TV – but, actually, it is when the writing bit of the brain does its hardest work. Believe me.

The third lot of time, Even More Time, is Time to rewrite, and rewrite and rewrite. But we’re not going to worry about that now. That’s for later drafts. For the moment, we’re thinking about the first draft.

As I’m sure you know, Time is never a neutral, abstract thing. Nor merely a clock-ticking-on-the-mantlepiece thing. Time for writing your novel is time not for other occupations, not for other people. It’s time stolen from your loved ones; time they will probably resent you not devoting to them. Time is closing the door behind you and not answering when people knock – not unless they knock very hard, and shout words like ‘Fire’ and ‘Bastard’ and ‘I’m leaving – I really am’.

In a way, writing is saying to your loved ones, ‘Go away, because I want to talk to you’. I want to talk to you in a more articulate and truthful way than I ever could if you were there in front of me. ‘Go away, because I want to talk to you.’

All of which explains why you’ll need the fourth thing, which is…

Some Selfishness

I could try to make this sound nicer – I could call it self-belief or determination or following your dream – but that’s not how it’s likely to appear to your loved ones, the ones outside the door, knocking, pleading.

I could try to make this sound nicer – I could call it self-belief or determination or following your dream – but that’s not how it’s likely to appear to your loved ones, the ones outside the door, knocking, pleading.

Self-belief without justification is always going to appear selfish, and until you write your novel there won’t be any justification. In lots of people’s eyes, until your novel is published by a publisher they have heard of, and appears in shops they frequent, and is reviewed in a newspaper they read, then it is unjustified. And in the eyes of a large minority, a book isn’t really justified until it has been made into a film starring an actor or actress they have heard of – thus saving them the trouble of having to read it.

However, writing rarely has a proper justification. Not in the strictest sense. Writing with justification is the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

There is a story about James Joyce, made up by Tom Stoppard and included in his play Travesties. Joyce is in the dock. The interrogator asks him, ‘What did you do during the Great War?’ To which Joyce replies, ‘I wrote Ulysses. What did you do?’

The only real justification for a piece of writing is that it is worth reading – or feeling guilty about not having read.

But Selfishness is, of course, not enough. You will also need…

Some Generosity

Because, without making it sound like geriatric nursing or tin-shaking for the NSPCC, writing is an act of generosity. A novel that isn’t essentially for other people to read isn’t worth writing. This is the ‘..I want to talk to you’ part, the part that comes after ‘Go away.’

Many writers claim they write only to please themselves. And I believe them – but only so far as to say this is what they need to tell themselves in order to write.

A well-formed sentence has a direction: towards the reader.

So far we have: Time, More Time, Even More Time, Some Selfishness and Some Generosity.

The next thing you need is a little more prosaic. It’s…

The Means

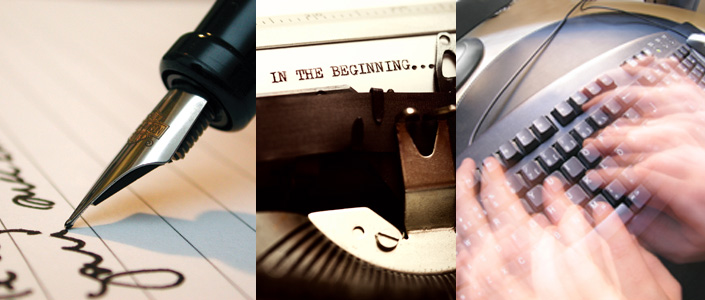

By The Means I mean the physical necessities of writing – a pen or pencil and some paper, or a computer.

By The Means I mean the physical necessities of writing – a pen or pencil and some paper, or a computer.

What you use is entirely your choice. If what works for you is to write in crayon on old cornflake packets or in chalk on the gashouse wall, it doesn’t really matter.

There are some drawbacks to the gashouse wall (though in these days of digital cameras, who knows?) I would have a few cautionary things to say about word-processing.

The first is that it makes things too easy. Although I am telling you the nine things you need to write a novel, the most important is probably contained in these five words: There are no short cuts.

The sheer physical labour of rewriting a novel, start to end, by hand would certainly make one consider the necessity of every single word; copy/paste does not do this.

Of the Evils of Word-Processing, copy/paste is Number 2. (Number 1 comes a little later. Read on.)

By Means I also mean a workplace. Ideally this would be, as Virginia Woolf put it, A Room of One’s Own. But if this isn’t, a library, café, train or park bench in spring or summer will do almost as well. Quiet, too, is probably recommended.

The next thing you need – there are only three more – is something much more abstract. It is…

A Discipline.

A Discipline. Not, I repeat, not a routine, though it might on the surface resemble one.

A routine is unhelpful because, when you miss it or mess it up, you are going to feel bad, and get disheartened, and stop writing.

I think the idea of a discipline is better than that of a routine, because it is more flexible.

A routine is ‘I need to be at my desk by nine o’clock and produce 400 words by lunchtime.’ A discipline is, ‘It would be nice if I could do about a page or so every day.’

Here are a couple of famous writers’ disciplines. They are American writers. I’m not sure why but American writers seem to be more open about the craft of what they do. Perhaps because they feel awkward when anyone emphasises the art aspect.

The first discipline is Ernest Hemingway’s:

“I always worked until I had something done and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day.”

This comes from his book A Moveable Feast – a memoir of Paris in the 1920s. It is perhaps the single most useful clue I have ever come across as to how novels get written.

The second discipline is from David Mamet’s A Whore’s Profession. Mamet is a notable dramatist, and also wrote the screenplay to Wag the Dog.

“As a writer, I’ve tried to train myself to go one achievable step at a time: to say, for example, ‘Today, I don’t have to be particularly inventive, all I have to be is careful, and make up an outline of the actual physical things the character does in Act One.’ And then, the following day to say, ‘Today I don’t have to be careful. I already have this careful, literal outline, and all I have to do is be a little bit inventive,’ et cetera, et cetera.”

American writers, particularly American male writers, can often go to extremes when they set their minds to a routine. Hemingway, later in his life, became very macho about things.

He wrote standing up, usually in his bedroom in his house in Cuba, using the top of a bookcase, on which room was cleared, to quote the Paris Review, “for a typewriter, a wooden reading board, five or six pencils, and a chunk of copper ore to weight down papers when the wind blows in from the east windows.” It gets better. Hemingway “stands in a pair of his oversized loafers on the worn skin of a Lesser Kudu – the typewriter and the reading board chest-high opposite him.” He told his interviewer, George Plimpton, that he began in pencil, then shifted to his typewriter when his writing was going extremely well or when he wrote dialogue. Each day he kept count of the words he produced: “from 450, 575, 462, 1250, back to 512, the higher figures on days Hemingway puts in extra work so he won’t feel guilty spending the following day fishing on the Gulf Stream.” Hemingway was a strange old man, as he himself might have put it, but, when it came to writing, no stranger than most.

Not to be outdone, here is John Steinbeck:

“He wrote eight hours a day, six days a week for forty years. He would sharpen twenty-four pencils each morning and write with them until each one was blunt. After many years of this regimen, he had to use his left hand to insert the pencil into the calluses on his writing hand because he was unable to pick up the writing utensil with his right hand. Every few months, he would sandpaper those calluses so he could continue to write.”

British writers are different. Ian McEwan, I heard, rewards himself with a Choco Leibnitz biscuit if he’s had a good morning.

I’m not asking you to sandpaper your calluses. But I might be able to give you a few hints about finding a good, productive discipline:

To start with, don’t count the hours (a person can easily achieve nothing in eight hours), but do have a set amount you must do before you finish: one page, two, more, of hand- or typewritten words.

Wordcount is an instrument of the Devil. Don’t use it more than once a week. Of the evils of Word-Processing, it is Number 1. Especially Live Wordcount.

If it’s a choice between writing badly and not writing at all, write badly. Your only responsibility is for the final draft.

Don’t try to make it perfect on the first draft. Roughness is a virtue at this stage, because roughness is easier to cut, to rewrite.

The penultimate thing you need is the one you’ll probably have thought of first…

A Yearning.

I’ve chosen this, rather than Idea. There’s nothing more likely to close you down than someone saying, ‘You have to have an idea. Now.’

But you need to have a strong sense that there’s something not quite there that should be.

A niggling sensation. A question. Okay, I give up – an Idea.

What does an Idea look/feel/smell/taste/sound like?

Well, you tell me.

But if it’s a really good one, it’s quite possible that, even if you told it me, I wouldn’t recognise it as an Idea – and certainly not as a really good one.

I would, incidentally, recommend that you don’t ever tell people your ideas. Unless they say, ‘That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever heard. Let me sell my house to finance you as you complete this great work,’ you are likely to be disappointed with their reaction. And this may put you off seeing the idea through to its end.

The problem of The Idea is the biggest one for writers just starting out. They return again and again to the question: What do I write? And this is, of course, the question I am least able to answer for you.

But the one thing I won’t repeat is the Great Wisdom of creative writing classes, i.e., Write What You Know.

This is likely to make you think not of what you Know but what you’reCompletely Bloody Sick to Death of.

Henry James, my favourite writer, had something neat to say about the relationship between writing and knowing, expression and experience, in his essay ‘The Art of Fiction’:

‘The power to guess the unseen from the seen, to trace the implication of things, to judge the whole piece by the pattern, the condition of feeling life in general so completely that you are well on your way to knowing any particular corner of it – this cluster of gifts may almost be said to constitute experience, and they occur in country and in town, and in the most differing stages of education. If experience consist of impressions, it may be said that impressions are experience, just as (have we not seen it?) they are the very air we breathe. Therefore, if I should certainly say to a novice, ‘Write from experience and experience only,’ I should feel that this was rather a tantalizing monition if I were not immediately to add, ‘Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost!’’

This is a much more difficult, and useful, thing to aim for. If you aspire to being one of those on whom nothing is lost, then ideas will come to you, I promise.

An idea can be an area of mess or confusion in your head, or a line of remembered real-life dialogue, or an enticing title, or an exquisite memory, or a feeling of dreadful foreboding. It’s something, in other words, that haunts you.

A Yearning.

The final thing you need is…

A Tone

For the first-time novelist, consistency of voice is one the hardest things to achieve. You probably won’t, to begin with, have anything approaching a style, but you will have to settle upon a tone. This can range from ‘Once upon a time…’ to ‘For a long time, my mother used to…’

Here, though, is the ultimate and very simple secret of writing a novel: If you write 1,000 words a day for 75 days, at the end of those 75 days you will have a novel-length-thing. This novel-length-thing may not be a great novel, or even a good novel, or even a novel, but it’s a lot closer to being all three than the nothing you had before.

Or as Gertrude Stein said, ‘The way to do it is to do it.’

So, to conclude, let us go through the 9 things you need to write a novel:

1. Time

2. More Time

3. Even More Time

4. Some Selfishness

5. Some Generosity

6. The Means

7. A Discipline

8. A Yearning

9. A Tone

You have no more excuses. If it’s in you, it can now come out.

Let it.

Find out more about creative writing courses at Birkbeck.