This article was contributed by Professor Zhu Hua of Birkbeck’s Department of Applied Linguistics and Communication

In his open letter published in the New York Times on 9 October, Michael Luo, who was born and grew up in the US, told of his encounter with a woman who yelled at him and his family, ‘Go back to China!’, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan when they came out of a church service. Puzzled by the event, his 7-year-old daughter asked ‘Why did she say, ‘Go back to China?’ We’re not from China.’

In his open letter published in the New York Times on 9 October, Michael Luo, who was born and grew up in the US, told of his encounter with a woman who yelled at him and his family, ‘Go back to China!’, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan when they came out of a church service. Puzzled by the event, his 7-year-old daughter asked ‘Why did she say, ‘Go back to China?’ We’re not from China.’

What Michael Luo experienced is ‘perpetual foreigner syndrome’, a problem facing many transnational individuals in everyday interactions, especially those who may look or sound different from the local majority. Back in 2002, Frank Wu, the first Asian American law professor at Howard University Law School, wrote specifically on how perpetual foreigner syndrome is instantiated through recurrent and seemingly innocent questions (which, admittedly, are much milder than what was hurled at Michael Luo):

Where are you from?’ is a question I like answering. ‘Where are you really from?’ is a question I really hate answering… For Asian Americans, the questions frequently come paired like that…. More than anything else that unites us, everyone with an Asian face who lives in America is afflicted by the perpetual foreigner syndrome. We are figuratively and even literally returned to Asia and ejected from America. (Wu 2002)

His point about what these questions can do strikes a chord with me. Having lived and worked in China and Britain and travelled to many parts of the world, I find questions like ‘where you are from?’ really difficult to answer. I never seem get it right and always end it up with the feeling that the self I present in my attempted answers is not real – it is fragmented some times, and rehearsed at others. If I say that I am from London, I know that the next question will be ‘where are you really from’. I have to look apologetic and confess that I ‘originally’ came from China more than 20 years ago and have lived in Britain longer than I had been in China. If I take the short-cut and tell people that I am from China, the next comment I am likely to hear is a compliment ‘but your English is so good!’. For a long time, I thought that this is just me, an applied linguist who is over-interpreting language use in everyday interactions, until I read Rosina Lippi-Green’s work on language, ideology and discrimination (1997/2012) and began to make connections with my observations on these instances of discourse in daily encounters and the existing studies including one of the strands of my work on Interculturality.

I refer to this kind of discourse that evokes or orients to one’s ethnicity or nationality either explicitly or implicitly as Nationality and Ethnicity Talk (NET). It includes questions or comments which, frequently occurring in small talk, aim to establish, ascribe, challenge, deny or resist one’s ethnicity or nationality. The questions and comments range from direct ones (e.g. ‘Where are your people coming from?’, ‘When are you going back?’, ‘Is it as hot as this where you are from?’, ‘What is it like back home?’ to more subtle ones (e.g. ‘Your English is so good!’). There is nothing inherently wrong with questions like ‘where are you from’. The question can be genuine – people would like to find out more about China, Japan or Korea or any other culture or they are simply interested in you as a person. But problems occur when those who are asking such questions appear to look for a certain answer and appear confused or disappointed when hearing an unexpected answer and those on the receiving end of such questions might have been asked the same questions 101 times. And of course, in Michael Luo’s case, it made him and his daughter feel like ‘foreigners’ in their own country

Despite growing acceptance of racial equality in post-industrialised societies, NET of the above kind reflects people’s hidden and flawed folk theories of race, reproduces and reifies cultural essentialism, and can result in exclusion and marginalisation of certain social groups. Jane Hill (2008) coined the concept of ‘folk theory of race’ to describe everyday assumptions that people have about race and ethnicity. Because the folk models or theories are often taken for granted, people tend to use them to ‘interpret the world without a second thought’. Folk theory of race can be in operation subtly and, on some occasions, it is almost invisible to those who apply it and/or those at the receiving end of it. Markus & Moya (2010) have unpicked the powerful, hidden, and flawed assumptions about the nature and meanings of race and ethnicity beneath the eight common conversations about race amongst American people. These include: ‘We’re beyond race.’ ‘Racial diversity is killing us.’ ‘Everyone’s a little bit racist.’ ‘That’s just identity politics.’ ‘Variety is the spice of life.’ ‘It’s a Black thing—you wouldn’t understand.’ ‘I’m___ and I’m proud.’ and ‘Race is in our DNA’. They argue that ‘these eight conversations give us the illusion of understanding, but they are narrowly based on limited, flawed, and of course, unstated assumptions … Also like stereotypes, these conversations are pervasive, they are difficult to change and they have powerful consequences for our actions.’

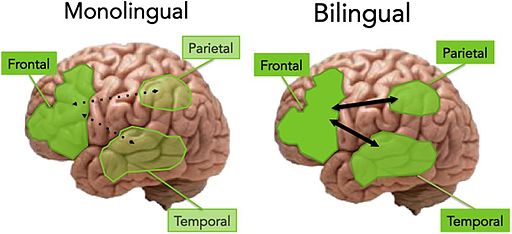

In my recently published article co-authored with Li Wei, we examine the significance of questions such as ‘where are you really from?’ in everyday conversational interactions. We discuss what constitutes NET, how it works through symbolic and indexical cues and strategic emphasis, and why it matters in the wider context of identity, race, intercultural contact and power relations. The discussion draws on social media data including youtube videos and a blog with the title of ‘It may not be racist, but it’s a question I’m tired of hearing’ by Ariane Sherine in the Guardian’s opinion column, Comment is Free. We argue that the question ‘where are you really from’ itself does not per se contest immigrants’ entitlement. However, what makes a difference to the perception of whether one is an ‘outsider’ as Michael Luo did – is the tangled history, memory and expectation imbued and fuelled by power inequality.

There have been reports of the increase in the number of racial insults at people who look and sound different since the EU Referendum. It is important that we pay closer attention to linguistic xenophobic, but it is equally important to be mindful of the significance of the more subtle ways of Othering as exemplified in NET.

Further reading:

- Hill, Jane H. 2008. The everyday language of white racism. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lippi-Green, Rosina. 1997/2012. English with an Accent. Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States. London: Routledge.

- Markus, Rose & Paula Moya (eds.). 2010. Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Wu, Frank. H. 2002. Where are you really from? Asian Americans and the Perpetual Foreigner Syndrome. Civil Rights Journal Winter 2002. 16-22.

- Zhu Hua and Li Wei (2016) “Where are you really from?”: Nationality and Ethnicity Talk (NET) in everyday interactions. In Zhu Hua & Claire Kramsch (eds.), Symbolic power and conversational inequality in intercultural communication, a special issue of Applied Linguistics Review 7(4), 449-470. The article can be accessed here.