Today is Holocaust Memorial Day 2021, a day that encourages remembrance in a world scarred by genocides. The 27 January marks the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest of the German Nazi concentration camps in Europe. During the Holocaust six million Jewish men, women and children lost their lives, so on Holocaust Memorial Day we honour and remember the memory of those who were lost and those who survived.

Over the years the Birkbeck Pears Institute for the Study for Antisemitism has produced podcasts that touch on different aspects of this history, through the lens of academics from a range of institutions. They are all free to listen to. There will be a live event on 2 February.

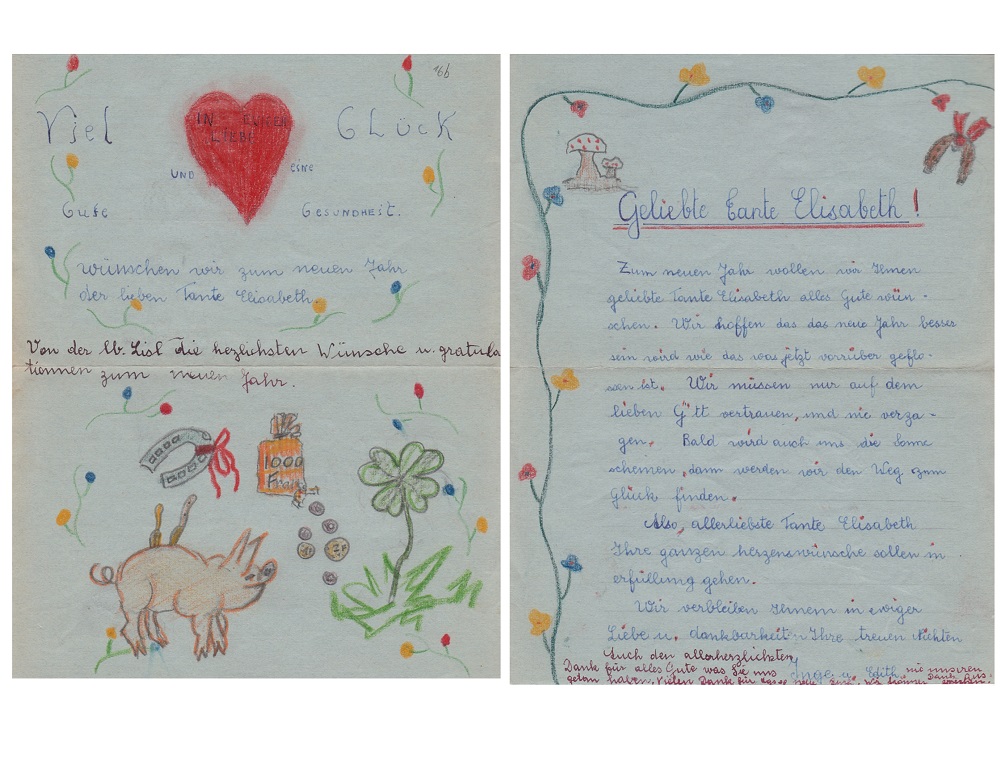

A letter from a child called Edith. Letters will be discussed as part of ‘ Holding on Through Letters: Jewish Families During the Holocaust’ a live online event on that will be held on 2 February.

1. A Bystander Society? Passivity and Complicity in Nazi Germany

Professor Mary Fulbrook, University College London, 18 February 2020

Exploring experiences of Nazi persecution, Professor Fulbrook analyses the conditions under which people were more or less likely to show sympathy with victims of persecution, or to become complicit with racist policies and practices. In seeking to combat collective violence, understanding the conditions for widespread passivity, Professor Fulbrook suggests, may be as crucial as encouraging individuals to stand up for others in the face of prejudice and oppression. Listen on the Pears Institute website.

2. ‘Warrant for Genocide’? Hitler, the Holocaust and the ‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion’

Professor Richard Evans, Birkbeck, University of London, 4 February 2019

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a notorious antisemitic forgery dating from the beginning of the 20th century, have been called ‘the supreme expression and vehicle of the myth of the Jewish world-conspiracy’. In his talk, Professor Evans takes a fresh look at the Protocols. He asks whether either the contents of the document or the evidence of Hitler’s speeches and writings justify these claims and examines the light they throw on the origins and nature of Nazi antisemitism. Listen on the Pears Institute website.

3. Antisemitism, ‘Volksgemeinschaft’ and Violence: Inclusion and Exclusion in Nazi Germany

Professor Michael Wildt, Humboldt University, Berlin, 27 January 2016

Professor Wildt explores antisemitism and violence in Nazi Germany. By definition, the Nazi Volkgemeinschaft – the national community, barred all Jewish Germans. National Socialist politics included the exercise of violence, and violence against Jews was a visible expression of the Volksgemeinschaft – it was antisemitism in action. Listen on the Pears Institute’s website.

4. Remapping Survival: Jewish Refugees and Rescue in Soviet Central Asia, Iran and India

Professor Atina Grossmann, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York, 28 January 2015

Professor Grossmann addresses a transnational Holocaust story that remarkably – despite several decades of intensive scholarly and public attention to the history and memory of the Shoah – has remained essentially untold, marginalized in both historiography and commemoration. Listen on the Pears Institute’s website.

On the 2 February, the Pears Institute in collaboration with the Institute of Historical Research will host a live event, that is free to attend.

5. Holding on Through Letters: Jewish Families During the Holocaust

Professor Debórah Dwork, The City University of New York

2 February 2021

Jewish families in Nazi Europe tried to hold onto each other through letters – but what to say, and about what to remain silent? In her presentation, Professor Dwork will trace how letters became threads stitching loved ones into each other’s constantly changing daily lives. Book your free place.