This post was contributed by Dr Justin Schlosberg, lecturer in Journalism and Media at Birkbeck’s Department of Film, Media and Cultural Studies. This was originally posted on Media Reform Coalition blog on Monday, 15 February 2016.

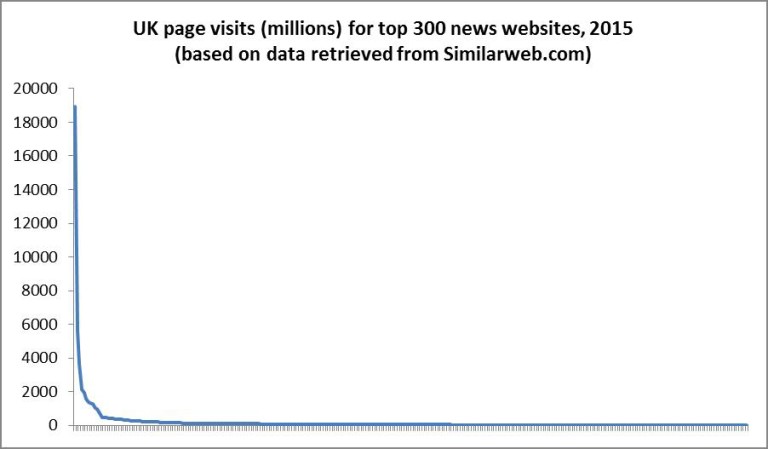

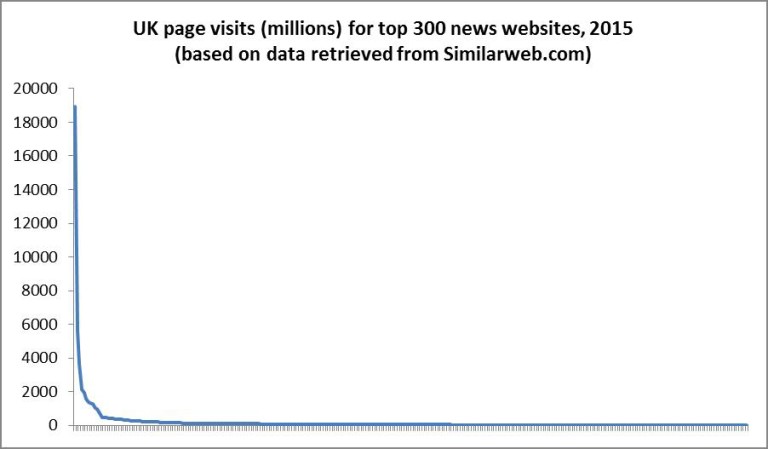

Last week a digital market research company reported that “the top 10 publishers make up a huge chunk of the U.K. media market and own more than half of the entire industry”. The statement was based on data that SimilarWeb collected over 2015, specifically the number of page visits to the top 300 news websites. They found that 65 percent of this traffic was concentrated in the websites of the top 10 news publishers, and the top five alone attracted more than half of all traffic across the sample.

Last week a digital market research company reported that “the top 10 publishers make up a huge chunk of the U.K. media market and own more than half of the entire industry”. The statement was based on data that SimilarWeb collected over 2015, specifically the number of page visits to the top 300 news websites. They found that 65 percent of this traffic was concentrated in the websites of the top 10 news publishers, and the top five alone attracted more than half of all traffic across the sample.

Optimists might consider that the mere existence of 300 news websites (which is itself far from an exhaustive sample of all news on the net), reflects the plurality of the online news sphere, at least compared to conventional platforms like television or print. On closer examination, however, the picture revealed is in fact one of heightened concentration, with not much more than a handful of major publishers able to reach across fragmented audiences, and thus play a potentially defining role in setting the wider news agenda. Previous studies have shown that such concentration can have a cascading or domino effect, with smaller outlets taking agenda cues from the big players. As one scholar put it, “in the age of information plenty, what most consumers get is more of the same”.

Blind Spots

To glimpse this reality we have to peel away a number of veils that make the gatekeeping and agenda setting power of mainstream news organisations not less significant, but rather less visible in the digital environment. Let’s start with the numbers. The lowest ranked news website – Pink News – still attracted some 16 million page views. Which sounds like a lot. But if we compare page views to unique visitors (as measured by the National Readership Survey among others), the average ratio works out to around 250:1. So 16 million page views over the course of the year will probably amount to an audience reach of around 60,000.

That’s still not a tiny amount given that we are at the bottom of the pile here. But it’s important to consider that the list includes many websites that are not really what we would generally think of as news providers. They are much closer to the equivalent of special interest magazines in the print world, focusing on music/film/sport/entertainment etc.

At the heart of plurality concerns is a conviction that healthy democracies depend on the circulation and intersection of diverse voices and perspectives. From this standpoint, it would seem odd to consider the plurality contribution of popularmechanics.com or cylclingweekly.co.uk as equivalent to a daily news provider, especially one that covers political news and current affairs.

One idea that captures the supposed plurality renaissance of the information age is the so-called long tail theory. According to this theory, the ‘personalising’ and tailored recommendations of search, social media and retail algorithms ensure that niche providers flourish and the ‘head’ (representing mainstream culture) dissipates over time. But if we plot Similarweb’s data into such a graph we find the opposite: the curve produces a highly defined ‘head’ followed by a very flat tail…

A decade after the long tail effect was first explained and predicted, not much seems to be changing. If anything, we may be experiencing a regression back to the kind of mass culture that revolves around superstars, best-sellers and mainstream headlines.

Another problem with the SimilarWeb data is that it does not capture news consumption via aggregators like Yahoo and social media sites like Facebook. Most of this content is produced by mainstream news brands which would make the head look even more concentrated if we were to attribute those page views to the original news sources.

OFCOM – the UK’s media regulator – repeatedly makes the opposite mistake by including these sorts of sites in survey data alongside what it calls ‘content originators’ like the BBC, Sky, Daily Mail, Guardian, etc. This again overestimates plurality by counting aggregators (sites that predominantly host content of other news providers) and intermediaries (sites that predominantly serve as gateways to third party news sites) as news sources in their own right.

Gateway Power

Uncover these blind spots and what we are left with, by any measure, is a highly concentrated picture of media power in Britain today. How has this happened? Given that so much of the traffic to news websites is ‘referred’ by intermediaries, the intricacies of Google’s news algorithm is a good place to start in addressing this question.

For some time now, Google has been weighting and ranking news providers according to a broad spectrum of what it considers to be the most reliable indicators of news quality. But it turns out machines are not much better at assessing news ‘quality’ than human beings. They may be free of subjective bias in one sense, but this means they rely (paradoxically) on quantitative measures of quality, which produces its own bias in favour of large scale and incumbent providers. One look at Google’s most recent patent filing for its news algorithm reveals just how much size matters in the world of digital news: the size of the audience, the size of the newsroom, and the volume of output.

Perhaps the most contentious metric is one that purports to measure what Google calls ‘importance’ by comparing the volume of a site’s output on any given topic to the total output on that topic across the web. In a single measure, this promotes both concentration at the level of provider (by favouring organisations with volume and scale), as well as concentration at the level of output (by favouring organisations that produce more on topics that are widely covered elsewhere). In other words, it is a measure that single-handedly reinforces both an aggregate news ‘agenda’, as well as the agenda setting power of a relatively small number of publishers.

Google engineers may well argue that the variety of volume metrics imbedded in the algorithm ensures that concentration effects are counterbalanced by pluralising effects, and that there is no more legitimate or authoritative way of measuring news quality than relying on a full spectrum of quantitative indicators. Rightly or wrongly, Google believes that ‘real news’ providers are those that can produce the most amounts of original, breaking and general news on a wide range of topics and on a consistent basis.

News plurality reconsidered

At face value, that doesn’t sound like such a bad thing. In a world saturated with hype, rumour and gossip, it’s not surprising that most people are attracted to news brands that signal a degree of professionalism. Part of Google’s corporate and professed social mission is to match users to the content they value most, and if most people prefer the mainstream, then that’s where the traffic will flow.

But there is no getting around the fact that Google favours dominant and incumbent news organisations. The company made its view clear when it stated in its patent filing that “CNN and BBC are widely regarded as high quality sources of accuracy of reporting, professionalism in writing, etc., while local news sources, such as hometown news sources, may be of lower quality”. But when the ‘mainstream’ is held as the ultimate benchmark of good quality news, we start to run into real problems for the future (and present) of media plurality.

Read the original article on Media Reform Coalition

For one thing, algorithms used by Google, Facebook and (to a lesser extent) Twitter actively discriminate against both prospective new entrants into the news market, as well as those that focus on topics, issues and stories beyond or on the fringes of the mainstream agenda. Yet these are precisely the kind of providers that need to be supported if we want to redress the symptoms of concentrated media power. In the post phone-hacking world, such symptoms continue to manifest in systematic ideological bias, as well as the enduring back door that links Whitehall to the Murdoch media empire.

As print newspapers start to fall by the wayside, news concentration online is of even greater concern. Policymakers, meanwhile, are distracted by dominant narratives that suggest the gatekeeping and agenda power once attributed to media owners has dispersed among ‘the crowd’, or transferred into the hands of intermediaries like Google and Facebook, or that the only plurality ‘problem’ today concerns the so-called filter bubble or echo chamber effects of personalised news.

There is truth in all of these claims but the unseen or overlooked reality is that the gatekeeping power of Google and Facebook works in tandem with that of mainstream news providers, mutually reinforcing each other around what is considered real, legitimate and authoritative news. As Des Freedman urges in his most recent book, “far from diminishing the importance of media moguls and tech giants, announcing the death of gatekeepers or lauding the autonomy of the public, we should be investigating the ways in which their power is being reconstituted inside a digital landscape”.

Find out more

Real press power resides in the the ability to suppress a scandal, at least as much as the ability to produce one. This is the lesson we learn repeatedly when journalists, facing the combined pressures of austerity, failing business models and an increasingly cautious and interventionist management decide enough is enough.

Real press power resides in the the ability to suppress a scandal, at least as much as the ability to produce one. This is the lesson we learn repeatedly when journalists, facing the combined pressures of austerity, failing business models and an increasingly cautious and interventionist management decide enough is enough.

Last week a digital market research company

Last week a digital market research company