The shock of a hung parliament following what only a few weeks ago looked certain to be a landslide victory for the Conservative Party has made this election one of the most unpredictable in recent generations.

The election also saw a number of Birkbeck alumni elected or re-elected as Members of Parliament: congratulations to: Kemi Badenoch (Con, Saffron Walden), Kwasi Kwarteng (Con, Spelthorne), Gloria Di Piero (Lab, Ashfield), Lisa Nandy (Lab, Wigan), Lucia Berger (Lab, Liverpool Wavertree), John McDonnell (Lab, Hayes & Harlington), Tulip Siddiq (Lab, Hampstead and Kilburn) and Sir Ed Davey (Lib Dem, Kingston).

Since the election was announced six weeks ago, Birkbeck academics have been using their expertise to offer insightful analysis of the unfolding political developments.

The Queen’s Speech

“While there is no specific Higher Education legislation the Government are still committed to an Industrial Strategy of which skills and training are a component and they are further committed to creating Institutes for Technology at locations throughout England. Whether these will embrace FE and HE qualifications or delivery we don’t yet know. The Conservative manifesto had also committed to a review of Tertiary education funding. While this is unlikely to happen more due to parliamentary arithmetic legislation would not be required should it choose to undertake this review. Finally, the Queen’s Speech is not the only opportunity for a Government to bring forward new policy. It is almost certain there will have to be a Budget and many positive measures for Birkbeck eg: PG Loans have come about that way. Let’s watch this space!”

– Jonathan Woodhead, Policy Advisor, Birkbeck

Let’s put the champagne on ice: the Commons’ missing women

Let’s put the champagne on ice: the Commons’ missing women

With a record high number of women elected to Parliament, was the 2017 general election something to celebrate? Professor Sarah Childs (who will join Birkbeck’s Department of Politics from 1 September – pictured left), Meryl Kenny (University of Edinburgh) and Jessica Smith (Birkbeck PhD student) re-assess the recent result and consider what it means for women’s political representation.

What can organizational psychology tells us about the calibre of our political leaders?

What can organizational psychology tells us about the calibre of our political leaders?

Organizational psychology provides substantial evidence about the characteristics of a successful leader, yet, as Dr Almuth McDowall explains, this knowledge is not consistently used when considering the suitability and capability of our political leaders in the UK.

We need to talk about Jeremy: why I was wrong about the 2017 General Election

We need to talk about Jeremy: why I was wrong about the 2017 General Election

Dr Ben Worthy, Lecturer in Politics, examines why so many people underestimated the effectiveness of Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign prior to the election.

Hung parliament

As it becomes clear that the most likely scenario following last week’s election is a minority Conservative government, with the backing of the Democratic Unionist Party, Dr Ben Worthy, Lecturer in Politics, discusses what a hung parliament is – and how long it is likely to last.

Results day reaction

Dr Jason Edwards, Lecturer in Politics :

Dr Jason Edwards, Lecturer in Politics :

“The election result reflects important and ongoing changes in British politics and society. First and foremost, it shows how far the old ways of doing politics have declined. The vitriol against Labour and Corbyn expressed in the traditional right-wing press seem to have had little impact. Social media now seems to be of much greater importance in motivating people to vote, and in shaping who they vote for.

“One effect of this is that the electorate is much more informed and policy-focussed than usually thought. This can be seen in attitudes towards Brexit. The lazy belief that most people either want to remain in the EU on current terms or have a ‘hard’ Brexit has been exposed. There is no clear divide between remainers and Brexiteers and people’s attitudes are much more nuanced.

“Above all, and some might say encouragingly, the election shows the clear limits of populism. The Conservatives played the populist card fully in this election and paid the price for it. UKIP were demolished. Labour, despite some calls to transform itself into a leftist populist movement, and while undoubtedly playing on some populist tropes (‘for the many, not the few’), set out a relatively clear and detailed programme that, despite widespread doubts about Corbyn’s leadership, attracted large numbers of people.

“Some will despair at the messy outcome of the election, but it marks significant shifts in society that offer great opportunities for – as well as threats to – democratic renewal.”

Dr Ben Worthy, Lecturer in Politics:

Dr Ben Worthy, Lecturer in Politics:

“Theresa May’s premiership looks over almost before it has begun. So how did it happen? And how do Premierships unravel? Here are three rules that, if broken, can get a Prime Minister in severe trouble:

- Don’t take too many risks

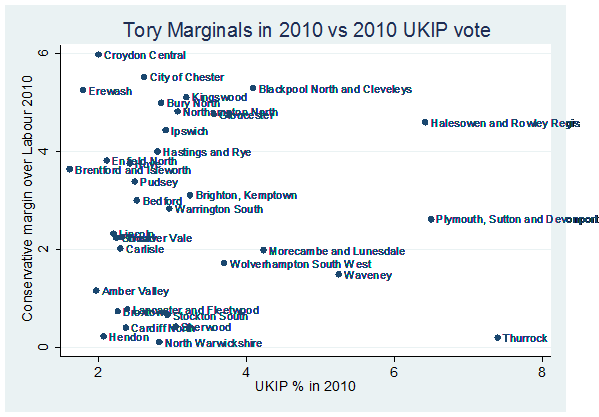

Leaders need to take risks but they should be calculated. Eventually a leader will simply run out of luck. Though she styled herself as the careful and thoughtful Vicar’s daughter she was actually a terrible risk taker. May gambled on being able to negotiate Brexit in secret (and failed), gambled on article 50 not going through Parliament (ended up in the Courts and failed) and then decided on an election. In the election she then gambled on a UKIP vote, her own leadership abilities and a set of untested policies (all of which failed). The old adage is that successive Prime Ministers are successively vicars and bookies. Theresa May posed as vicar but punted like a (rather reckless) bookie.

- Don’t underestimate your opponents

May clearly believed she could beat her rival and capitalise on his unpopularity. She thought wrong. Corbyn has energised young voters and, unbelievably, also appears to have won over the over-65s, gaining a remarkable 40% of the vote. Corbyn’s campaign has somehow united Remainers and Leavers and young and old. It may be, as some have argued, that the non-stop Conservative and right-wing media barrage at Corbyn boomeranged straight back at them. After two years claiming the Marxist extremist Corbyn would have us all ‘wearing overalls and breaking wind in the Palaces of the mighty’ the public just saw a reasonable, positive man promising more money for public services.

- Don’t overestimate yourself

Hubris is always lurking. May clearly somehow came to believe that she could carry an election based on herself, a kind of cult of personality built around her ‘strong and stable leadership’. The campaign ruthlessly exposed May’s many weaknesses and Michael Crick memorably said how ‘strong and stable’ had become ‘weak and wobbly’. In the space of six brief weeks, as Paul Waugh put it ‘the cautious pragmatist allowed herself to be portrayed both as a Leave-loving zealot and a flip-flopper’.

So now Theresa May’s premiership is unravelling before our eyes. Whatever deal is done with the DUP May is in her end game. Any Prime Minister that has to announce they won’t resign is already in deep, deep trouble. She has few allies and has fallen out with her Chancellor and isolated herself from her party. Even if May survives and limps on, she is damaged, captured and will be portrayed as being controlled by others: hanging on by her constitutional responsibility rather than her authority. Theresa May broke the three rules and snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.”

Consequences for Higher Education

Consequences for Higher Education

Jonathan Woodhead, Policy Advisor at Birkbeck:

“As the dust settles on what has been an extraordinary General Election campaign and result we ought to take time to see what this means for Education and Universities in particular. The ink hadn’t even dried on the Higher Education Act when the election was called and that Bill was as a result of a number of changes committed to in the 2015 Conservative manifesto. It shows how long the political process can take.

At the start of the election campaign and the subsequent manifesto launches it was quite clear that Education along with Brexit and Social Care would become one of the key issues. Labour’s commitment to scrapping tuition fees and introducing grants was a bold policy (costed around £10bn) but was clearly designed to appeal to the under-25s. This is a demographic that rarely voted and felt, particularly after the EU Referendum that they were not being heard. Many seats where universities had residential accommodation saw surges in the electoral roll. Curiously when the Lib Dems tried the same policy in 2010 which secured them a record 57 seats but when in Coalition and compromises had to be made it was abandoned and support from students ebbed away. On top of scrapping fees Labour also offered a review into lifelong learning which would have been relevant to Birkbeck but little detail was given.

The Liberal Democrat manifesto went into some detail about research funding and restoring student grants again to appeal to its university heartlands of Cambridge, Sheffield Hallam and Bath however they were only successful in the latter of these seats. While the Lib Dems wanted to put Brexit at the heart of the election campaign it seems that the electorate didn’t have the same priorities.

Turning to the Conservative manifesto there is mention of a Tertiary Funding review, the creation of Institutes for Technology and the Industrial Strategy Green paper – all with a focus on Education and Skills. There is also a looming question as to whether there will be further restrictions on international students coming to the UK. Depending on the stability of the Government it will remain to be seen how many of these manifesto pledges can be implemented or whether we will in fact be in election mode so soon after this one…”

How people decide who to vote for

Politics Professor Rosie Campbell reported on how people actually decide how to vote for the BBC, noting that ‘more of us are changing our minds,’ citing the framing of campaigns by the media, as well as major national or international events (such as recent terror attacks), and emotional influence as likely to change the course of a vote.

Politics Professor Rosie Campbell reported on how people actually decide how to vote for the BBC, noting that ‘more of us are changing our minds,’ citing the framing of campaigns by the media, as well as major national or international events (such as recent terror attacks), and emotional influence as likely to change the course of a vote.

Iconography in politics

Sue Wiseman, Professor of Seventeenth-Century Literature at Birkbeck discussed the iconography of hair of different politicians, and how it affects perceptions of the politician.

Theresa May – leaking leadership capital?

Shortly before the election, Ben Worthy and Mark Bennister commented on the diminishing leadership capital of the Prime Minister, and how leadership can be measured.

This article was contributed by

This article was contributed by