Sidhant Maharaj is an intersectional queer feminist activist from Fiji, currently pursuing their Masters in Gender and Sexuality Studies at Birkbeck, University of London.

Greetings, I’m Sidhant! I thought Pride Month would be an opportune moment to explore the vibrant and inclusive community surrounding Birkbeck. London, known for its rich history and diversity, offers an array of activities and events that celebrate LGBTQ+ pride and promote intersectionality.

Greetings, I’m Sidhant! I thought Pride Month would be an opportune moment to explore the vibrant and inclusive community surrounding Birkbeck. London, known for its rich history and diversity, offers an array of activities and events that celebrate LGBTQ+ pride and promote intersectionality.

What is Pride and why is it important?

Pride is an annual celebration of LGBTQ+ identities, cultures, and communities. It originated as a commemoration of the Stonewall Riots of 1969, a pivotal moment in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. Pride Month, celebrated every June, serves as a reminder of the struggles and triumphs of the LGBTQ+ community, advocating for equal rights, acceptance, and visibility.

Pride is important because it fosters a sense of belonging and community among LGBTQ+ individuals, promoting acceptance and love. It provides a platform to address ongoing issues of discrimination, inequality, and violence against LGBTQ+ people. Pride events and parades are not just festive occasions; they are acts of resistance and solidarity, reinforcing the message that everyone deserves to live authentically and without fear. Celebrating Pride means honouring the past, advocating for the present, and inspiring hope for a future where diversity is celebrated, and equality is a reality for all.

Here’s a guide to making the most of Pride Month in and around Birkbeck.

- Participate in the London Pride Parade

The annual London Pride Parade is a must-attend event, drawing thousands from around the globe. This year, the parade will take place on June 29th. The parade, known for its exuberant floats, music, and performances, highlights the strength and unity of the LGBTQ+ community. As a student, consider joining one of the university groups marching in the parade, which is a fantastic way to show solidarity and meet like-minded individuals.

Here is a list of other upcoming Pride events you should look out for:

- London Trans+ Pride:London Trans+ Pride will take place on Saturday 27 July 2024

- UK Black Pride:UK Black Pride is once again taking place in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park on Sunday 11 August 2024

- Bi Pride UK 2024: Bi Pride is taking place on Saturday 31 August at the University of West London, Ealing

- Visit the LGBTQ+ Cultural Institutions

London is home to several museums and galleries that celebrate LGBTQ+ history and culture:

- The British Museum: Discover artifacts and stories that illuminate the lives of LGBTQ+ people throughout history. Join their LGBTQ+ tours for a unique perspective. The British museum has a number of Pride events this year, be sure to check them out.

- Queer Britain: The UK’s first national LGBTQ+ museum, Queer Britain, located in King’s Cross, celebrates the stories, people, and places that have shaped the queer community.

- Bishopsgate Institute: Home to the UK’s most comprehensive LGBTQ+ archives, this institute hosts regular exhibitions and talks on queer history.

- Engage with Local LGBTQ+ Organizations

Connecting with local organizations can enrich your experience and provide support networks:

- Stonewall: A prominent LGBTQ+ rights charity, Stonewall offers volunteer opportunities and campaigns that you can get involved in.

- Twitter: @stonewalluk

- Instagram: @stonewalluk

- Switchboard LGBT+ Helpline: Volunteering here not only supports the community but also deepens your understanding of the issues faced by LGBTQ+ individuals.

- Twitter: @switchboardLGBT

- Instagram: @switchboardlgbt

- Attend Queer Performances and Events

Theatre, performance art and queer safe spaces play a crucial role in LGBTQ+ culture. London offers numerous queer-themed activities:

- The Common Press: Located in Bethnal Green, The Common Press is a community-oriented space that hosts a variety of events including queer readings, performances, and workshops. It’s a fantastic venue for experiencing grassroots LGBTQ+ culture and arts.

- Twitter: @commonpressLDN

- Instagram: @commonpressldn

- The Royal Vauxhall Tavern: A historic venue for drag performances, comedy nights, and cabaret shows, fostering a lively and inclusive atmosphere.

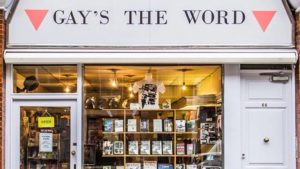

- Explore Queer Literature

Literature offers profound insights into the queer experience. Check out these local literary spots:

- Gay’s the Word: The oldest LGBTQ+ bookstore in the UK, located in Bloomsbury, offers a wide range of queer literature, including fiction, non-fiction, and academic texts.

- Twitter: @gaystheword

- Instagram: @gaysthewordbookshop

- Foyles Bookshop: Located on Charing Cross Road, this iconic bookstore often hosts events featuring LGBTQ+ authors and poets.

- Twitter: @Foyles

- Instagram: @foylesforbooks

- Participate in Academic Discussions and Workshops

Birkbeck itself hosts various seminars, workshops, and discussions on gender and sexuality:

- Centre for Researching and Embedding Human Rights: Attend talks and seminars that address contemporary issues in gender and sexuality studies.

- Birkbeck Gender and Sexuality (BiGS): Engage with fellow students and academics in discussions that promote understanding and activism within the field.

- Enjoy Social Spaces and Nightlife

London’s nightlife is diverse and welcoming:

- Heaven: One of London’s most famous gay clubs, offering vibrant nightlife experiences with themed nights and renowned DJs.

- Twitter: @heavenLGBTclub

- Instagram: @heavenLGBTclub

- G-A-Y Bar: Located in Soho, this bar is perfect for meeting friends and enjoying a night out in a lively, inclusive environment.

- Twitter: @JeremyJoseph

- Instagram: @gaylondon

- Ku Bar: Also in Soho, Ku Bar is known for its friendly atmosphere and fantastic cocktails.

- Twitter: @KuBar

- Instagram: @kubarlondon

- Explore Queer-Friendly Cafés and Restaurants

Soho, in particular, is brimming with LGBTQ+-friendly eateries:

- Balans Soho Society: A welcoming spot offering delicious food and a great atmosphere.

- Twitter: @BalansSohoSoc

- Instagram: @balanssohosociety

- Circa Soho: A stylish gay bar offering great drinks and a lively dance floor.

- Twitter: @CircaSoho

- Instagram: @circasoho

- Support Queer Businesses and Initiatives

Supporting local queer-owned businesses and initiatives helps strengthen the community:

- Pride Pop-Ups: During Pride Month, various pop-up shops and markets feature queer entrepreneurs showcasing their products.

Final Thoughts

As a student at Birkbeck, University of London, you are part of a vibrant, diverse, and inclusive community. Engaging with the activities and events listed above will not only enhance your understanding of LGBTQ+ issues but also help you forge lasting connections. Embrace the spirit of Pride, celebrate diversity, and continue to advocate for equality and intersectionality in all aspects of life.

More information:

- Study Gender and Sexuality Studies at Birkbeck

- Connect with Sidant on Twitter and Instagram

Dr Dominic Janes

Dr Dominic Janes