Gabriel Burne, an MA History of Art student, discusses the legacy of the historical figures whose statues have been removed and how the current debates around these monuments should encourage deeper discussion about Britain’s violent and racist past.

“The air of England is too pure for any slave to breathe.” Allegedly this was said during the trial of Shanley v. Harvey, a case where a British man, Shanley, was attempting to recoup a substantial sum of money given to Harvey by Shanley’s niece on her death bed. The basis of the claim was that Shanley had bought Harvey as a child slave to England some 12 years earlier and given him to his now deceased niece. I heard it quoted during my undergraduate degree in History in a debate about the role that slavery played in the UK economy. Even though many slaves were bought, sold and owned on the British Isles, the quote was employed as evidence of Britain’s relationship to slavery being distinct from that of the United States. Whilst the quote was likely never uttered, and the sentiment it reflected false, its popularisation reflects this Island’s complex and unresolved relationship to its violent and racist past. Much of Britain’s history of racial violence is hidden, existing only as ghosts haunting the otherwise heroic narrative of Britain and its heroes. When I embarked on a Master’s degree at Birkbeck in History of Art, it was these ghosts I wanted to know more about, in an effort to reinsert the lives and horrors which these spectres recall back into popular British history.

For many of us in Britain, our understanding of racism is taught from the perspective of the United States. The civil rights movement – Martin Luther King, the KKK, Malcolm X and segregation – are all things many in the UK have an understanding of. They are core aspects of our national curriculum and whilst they teach us important lessons on white supremacy, they create a sense of separation from the problems that exist here in Britain. To learn more about how we honour and adulate those who created this system of white supremacy in the UK, I took a module called “Slavery and its Cultural Legacies.” My reading for the course took me to some of the black theorists writing in the US currently – particularly Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. Whilst their writing was specifically speaking to an American experience, I felt there was a lot to be learned from their ideas here in the UK. Sharpe and Hartman speak of “the wake” and “the afterlife” of slavery respectively. Slavery’s violence lives on in white supremacy, a condition which is constitutive of contemporary Britain. The Research Project that I am currently writing examines the British monuments that often honour and/or neglect to acknowledge racial violence as part of the individual championed legacy.

In February this year, I went to the London Docklands Museum organised as part of the module. We were taken through the museum’s exhibition on slavery – London, Sugar & Slavery. The exhibition itself speaks of the ubiquity and brutality of the slave trade in the UK and is situated in the very building that was a hub for receiving the imported goods from Britain’s slave plantations. Whilst the museum takes steps to foreground black voices and highlight some of these hidden histories, a walk onto the docks outside the entrance reveals some stark reminders of this unconfronted violence. A cocktail bar serves “plantation punch” as a drink on the menu. And towering just in front of that sits a statue honouring prominent British slave trader Robert Milligan, who by the time of his death in 1809, owned two sugar plantations and 526 slaves in Jamaica.

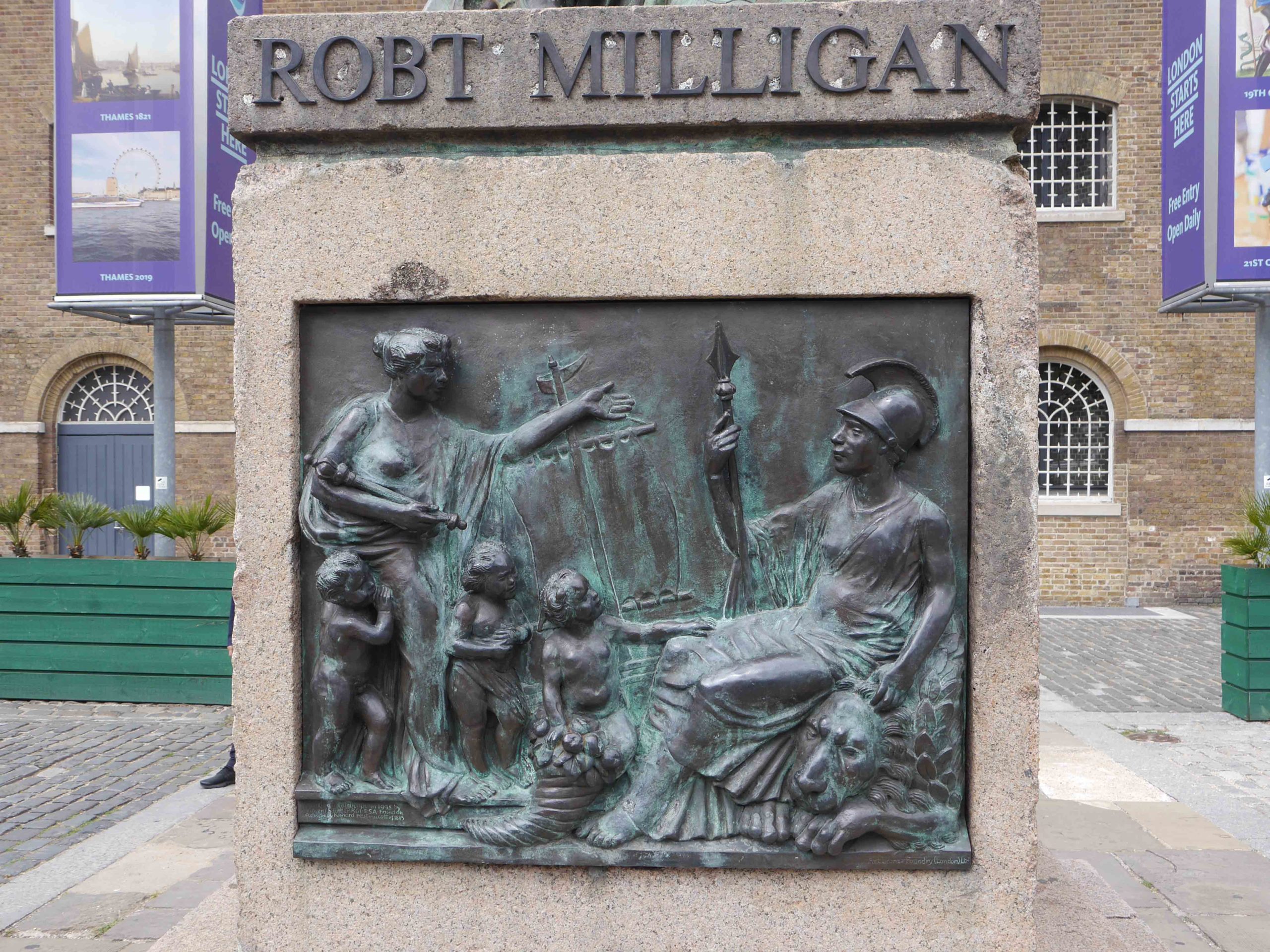

I stared up at the dead metal eyes of Milligan looking out across the docks, posed as if smiling upon an arriving ship, bountiful with the fruits of his murderous plantations. The plinth on which the statue stands illustrates his achievements with a relief that depicts Britannia seated on her tame-looking British lion, whilst the female figure of commerce offers her riches and at her feet three cherubs help carry the bounty. The mast of an approaching ship is visible in the background, the very ships whose docking in Greenwich Milligan would have cheered.

In romanticising the wealth men like Milligan brought lady Britannia, statues such as this obscure how this wealth originated in racial violence – the lucrative cargo carried aboard these ships, and which both Milligan and Britain celebrate, were produced by the enslaved. The continued existence of these statues’ silences new voices and alternative histories under the weight of the historical indulgence upon which Britain’s current power structures relies, that of a grotesque imperial and racially violent past located elsewhere, in far-off lands.

When I embarked on researching the Milligan statue, along with the statues of the slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol and Cecil Rhodes in Oxford, George Floyd was still alive. The protests catalysed by his murder at the hands of three police officers have since led to each either being removed or torn down by activists. This totally unforeseeable set of events taking place as I research these statues has left my project at an incredible crossroads that changes from day-to-day. The removal of the Colston statue in Bristol by activists, followed by its symbolically poignant casting into the harbour, prompted the Milligan statue to be removed by the local council days later. It has just been announced that the Cecil Rhodes statue that sat on Oriel College and has for years been the subject of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, will likewise be removed. Commenting on these events, the Prime Minister stated that to remove these statues is to “lie about our history and impoverish the education of generations to come.” This statement is reminiscent of the same mental gymnastics performed by the relief that sits below the Milligan statue. Rather than being moved by watching the monuments to these men fall and cheering what is, at best, a small step toward confronting this violent past, Johnson continues the exercise of obfuscation. Not once does he mention precisely what he thinks this history is, yet he claims it to be the “truth”. To engage in the actual process of discussing this history is to highlight what these statues hide: that of a British slave-trading and imperial past not confronted, and the “afterlives” of the British slave in which non-white people in this country must live.

At the time of an anti-racist uprising alongside offering solidarity to America, we must also reflect on the constitutive role slavery and white supremacy have played in British history. As the actions of many demonstrators have movingly and powerfully shown, it is imperative to reflect on what voices are hidden when men like Colston, Milligan and Rhodes are celebrated. We must remind ourselves that the enslaved also breathed the UK’s air “too pure.”

Further reading:

On the British abolitionist movement and the Haitian revolution

CLR James, The Black Jacobins, (Random House: New York, 1989)

US Black studies theorists and the afterlives of slavery

Saidiya V Hartman Lose your mother: a journey along the Atlantic slave route (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2007)

Christina Sharpe In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2016)

Fred Moten In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (University of Minnesota Press, 2003)

For British involvement in the slave trade

Paul Gilroy The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness (Verso, London, New York, 1993)

Catherine Hall Legacies of British Slave-Ownership (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016)