This post was contributed by Professor Penelope Gardner-Chloros, from Birkbeck’s Department of Applied Linguistics and Communication.

This post was contributed by Professor Penelope Gardner-Chloros, from Birkbeck’s Department of Applied Linguistics and Communication.

I recently had the pleasant experience of being invited to Malta for the International Conference on Bilingualism. Not having been there before, this provided an excuse to visit the country and to find out a bit more about its fascinating history and linguistic situation. Maltese is the only Semitic language written in the Roman alphabet. It derives from the Arabic spoken in Sicily between the 9th and 12th century, but its lexical stock is largely made up of Italian/Sicilian and other Romance borrowings. As it was under British rule for more than 170 years, gaining independence in 1964, English is a co-official language with Maltese and there are now large numbers of English borrowings. Much of the population is bilingual in Maltese and English.

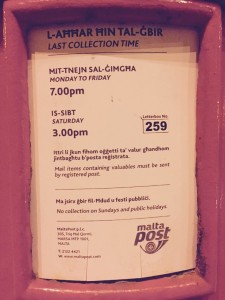

The photograph of a – typically British – Maltese letterbox illustrates the situation. The text in Maltese is made up of Arabic elements, including the days of the week. Blended seamlessly into this are Italian expressions which are equally integrated parts of the language: underneath ‘3pm’ we read about “oggetti ta’ valur”, “posta registrata” and lower down “festi pubblici” – all very recognizably Italian. English is also represented, being a co-official language, resulting in a code-switched text which represents the various origins and layers of the language, viewed through the lens of officialdom. Bi/trilingual documents as such are commonplace in many countries. But here the admixture of Romance, both entirely traceable and distinct from the Arabic, is reminiscent of so-called ‘mixed languages’: due to specific historical circumstances, a few unusual languages, such as Michif (French and Cree) or Media Lingua (Spanish and Quechua) take their lexis and grammar from different sources.

The photograph of a – typically British – Maltese letterbox illustrates the situation. The text in Maltese is made up of Arabic elements, including the days of the week. Blended seamlessly into this are Italian expressions which are equally integrated parts of the language: underneath ‘3pm’ we read about “oggetti ta’ valur”, “posta registrata” and lower down “festi pubblici” – all very recognizably Italian. English is also represented, being a co-official language, resulting in a code-switched text which represents the various origins and layers of the language, viewed through the lens of officialdom. Bi/trilingual documents as such are commonplace in many countries. But here the admixture of Romance, both entirely traceable and distinct from the Arabic, is reminiscent of so-called ‘mixed languages’: due to specific historical circumstances, a few unusual languages, such as Michif (French and Cree) or Media Lingua (Spanish and Quechua) take their lexis and grammar from different sources.

Given all these circumstances, the contemporary issue of code-switching, where people alternate languages on a daily basis, is a fact of life in Malta. It was also an important focus at the conference. I myself have rarely met a non-linguist who has heard of code-switching; but on visiting a small restaurant in Malta, and explaining to the affable owner that I was there for a Bilingualism conference, she remarked casually that bilingualism was a big issue in Malta – “and”, she continued, “we also do a lot of code-switching”. Having recovered from the shock of finding a normal person who had heard of my specialism, I went back to the conference and listened to a talk by a young researcher who had carried out a linguistic survey among 120 or so Maltese informants. She reported that one sub-group – considered by others to be snobbish or show-offs – code-switched copiously. Her talk gave rise to the most impassioned and vituperative argument I have ever heard at an academic conference – so impassioned, in fact, that I found it difficult to establish the exact basis of the disagreement. Suffice it to say that it was about who code-switched to whom in Malta, why and when. One elderly participant in the discussion, somewhat alarmingly, threatened to have a heart attack on the spot.

The organisers later apologized for their colleagues’ tempestuous reaction and behaviour. But I myself came out strangely energised by the thought that my little corner of academia could give rise to such passions. Malta may be a small country, but it is a – still under-researched – treasure trove for linguists, and it is invigorating to witness a linguistic debate which so clearly carries on into the street.

Other blog posts by Professor Gardner-Chloros

Other blog posts about linguistics:

- Why “younger” is not always “better” with foreign language learning, by Professor Jean-Marc Dewaele

- “Most obscene article of a peer-reviewed scientific article” – an amusing award for a serious academic paper, by Professor Jean-Marc Dewaele

- Multilingualism in psychotherapy, by Professor Jean-Marc Dewaele

- Exploring Intercultural Communication: Language in Action, by Professor Zhù Hua

- Pardon my foreign accent!, by Professor Jean-Marc Dewaele