MSc Politics, Philosophy and Economics student Sonia Joshi argues that the western approach to

addressing climate change is far from equal.

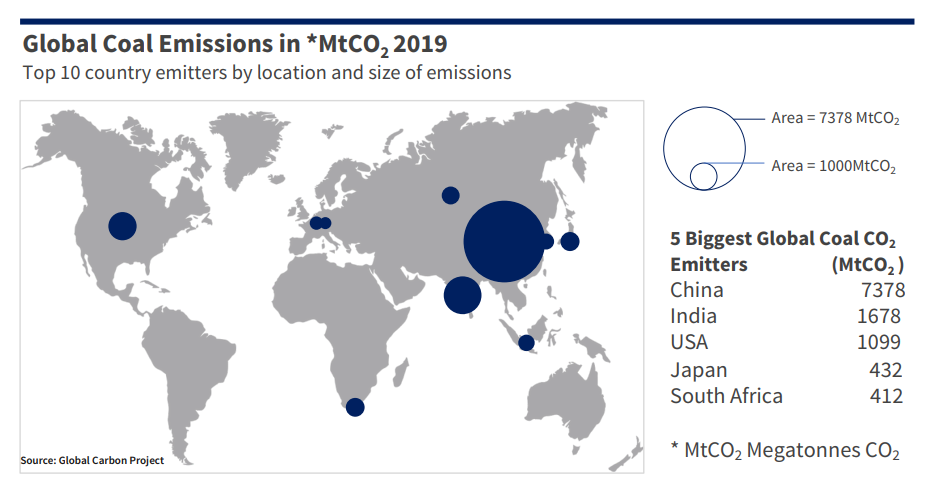

COP26 ended with more of a whimper than a bang. Last minute changes proposed by India and backed by other coal-emitting countries requesting the ‘phase out of unabated coal power’ to be changed to ‘phase down’ were considered a dilution of already wavering commitments. The International Energy Agency recently reported that in 2021 the world consumed more coal-fired electricity than ever before. India is the second largest global emitter of CO2 from coal whilst also suffering from the ravages of climate change, including a high susceptibility to deadly flooding, famines and air pollution.

As one of the biggest polluters and a country most at risk from the fallout of climate change, should and could India be doing more to phase out coal? The answer depends on how you frame the question.

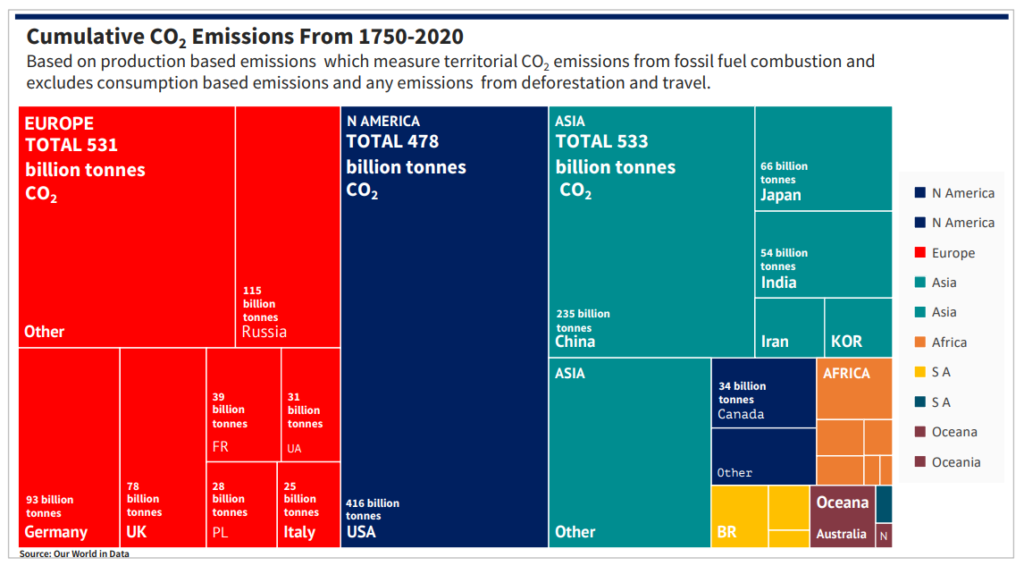

India has been hit hard after a COVID-19 induced recession with an additional 75 million people in poverty; cheap energy is essential for its recovery. India along with other emerging nations argue that the Global North’s rise in economic prosperity has been accelerated by its extraction and consumption of fossil fuels for over 200 years; according to a recent study, since 1850 in fair share terms the G8 countries (USA, EU28, Japan and Canada) have overshot their ‘carbon budget’, being responsible for 85% of aggregate carbon emissions despite only accounting for 12% of the global population.

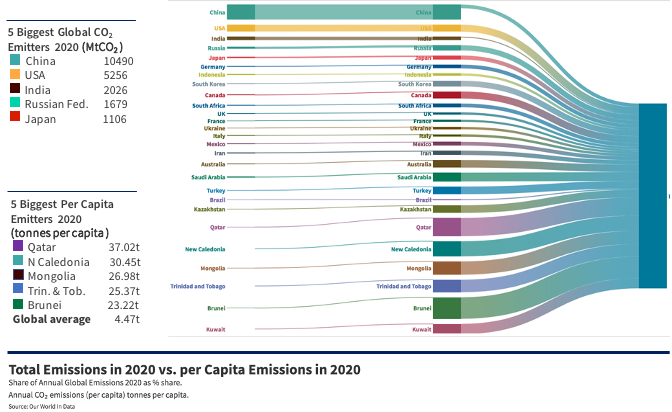

In contrast, India is in credit of 90 billion tonnes of CO2 or 34% of the total credit. When accounting for CO2 emissions per capita, the impact of wealthy nations on atmospheric CO2 is even more striking; Qatar takes the top spot, USA drops to 14th place and India falls to 134th. India’s per capita energy use is in fact extremely low; approximately one third of the global average, and one tenth of the USA average.

For now, India needs coal to help keep electricity flowing in an already resource-constricted population. Coal is necessary for 70% of its current electricity generation, with the State-owned Coal India Limited employing 21 million people. Despite this, a significant percentage of the 1.4 billion population still has no access to electricity. Fair share matters if the atmospheric commons have a finite capacity for CO2. With this calculation in mind, one could argue that members of the G8 such as the USA, one of the highest gross and per capita emitters, should be doing more to decelerate coal usage to buy time for other emerging nations to transition.

India is clear it needs to phase out coal; grass roots movements and labour organisations, including the 2 million strong National Hawkers Federation, regularly highlight the impacts of pollution on India’s cities and consistently call for a transition to renewable energy. However, a rapid decoupling from coal would not only leave millions in the dark but also create huge swathes of unemployment creating a political and humanitarian crisis.

An understanding of India’s predicament helps to shed light on how much progress was made by India in COP26 and how much more is needed. India’s government has pledged to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by 45% and obtain half of its energy requirements from renewable sources by 2030. For India to participate in a green transition, it will need funding to help economic diversification, investment in improving efficient coal use, green technologies and distribution of infrastructure to roll out renewables such as solar panels. Industry restructuring could provide alternative, sustainable and ecological opportunities for employment outside of fossil fuel intensive industries, helping the economy and the people decouple from climate disasters.