Zambia-born Kasoka Kasoka, who describes himself as a very proud ‘Birkbeckian’ alma mater, reflects on his time working on a PhD in Law at Birkbeck and his achievements since graduating in 2018.

Tell us about your education before Birkbeck

I am from Lusaka and Zambian. In 2007 I moved to the UK where I enrolled to study for a Bachelor`s degree through the University of London International Programmes. I obtained a Bachelor`s degree in Law in 2011. Upon the completion of my degree I was admitted to study at Maastricht University in the Netherlands where I studied for a Masters degree in Forensics, Criminology and Law. I obtained my Master`s degree in 2013.

Why did you choose Birkbeck?

Firstly, I decided to enrol here because of Birkbeck`s massive ranking as one of the best research universities in the World. And yes, it is! Secondly, I applied to study here because I was attracted to the College`s interdisciplinary research study approach. As a result, my research as a doctoral student cut across; law, human rights, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, history, bioethics, and public health. Engaging in an interdisciplinary research project afforded me a rare opportunity to become an interdisciplinary thinker, be open-minded, and embrace new ideas.

Thirdly, true to its name as a research-intensive university, Birkbeck comprises of academics and researchers who are renowned experts in their fields. Thus, my great former PhD supervisors, Professor Matthew Weait and Dr Eddie Bruce-Jones, are very respected researchers and authorities in their various fields. They are exceedingly knowledgeable and down to earth. And finally, but not exhaustively, I decided to study here due to the supportive student and staff community at Birkbeck. I indeed received a lot of support during my study from fellow PhD students, academic and research staff, and administrative staff members.

What were your relationships like with staff and other students?

I loved the critical approach to study and work culture at Birkbeck. I found my fellow PhD students to be really smart, friendly and supportive – this was endearing. As if this was not enough, both academic and non-academic staff were very approachable, attentive and supportive. I had a lot of academic staff who were not my PhD supervisors avail me with research insights and suggested various research material to read – as a goodwill gesture. This was priceless in my doctoral study journey!

Inevitably, I was sad to leave Birkbeck when my studies came to a conclusion, to leave behind such a great community. Nonetheless, I am still happy that I have stayed in touch and maintained the various friendships and networks I had the privilege of forming while studying at Birkbeck. Indeed, “once a Birkbeckian forever a Birkbeckian”!

It was a great honour to forge invaluable friendships and networks with students and staff members from diverse backgrounds. I consider Birkbeck to be one of the most diverse universities in the UK.

Did you use any of Birkbeck’s additional support and activities?

I had the opportunity to intuitively avail myself to various societies and student clubs at the University, including various PhD students` social groups. Birkbeck has a lot of societies and social groups with various activities. So, I was always happy to retire from my studies to unpack my mind by joining fellow students for some good fun. I especially enjoyed playing football! As they say “all work and no play make Jack a dull boy”!

Can you tell us more about your research project?

The purpose of my research was to investigate and analyse the appropriateness of individual autonomy in the context of informed consent HIV testing requirements in Zambia, and sub-Saharan African countries by extension.

Tell us about your experience of living in the UK.

I really loved living in London. London is no doubt one of the greatest cities to live in. What I liked most about the city is the diversity of its population. Thus, I was privileged to meet many people from every part of the world who brought with them various rich cultures, including great cuisines! With such a profoundly rich experience I agreed with Robert Endleman (1963) who observed that human beings in terms of cultures “are vastly various and yet laughably alike”! I also loved English pub food! And the museums, wow! – museums were often my favourite place of respite whenever I needed to briefly divorce myself from the usual business of life and time-machine myself into the past to admire and converse with ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Persians, Africans, Americans, Europeans and Indians who had no internet! And behold, the British Museum is only about three minutes-walk from Birkbeck! London is also pregnant with breath-taking gothic cathedrals and other non-church buildings.

(I need to mention that there are much more things for one to see and enjoy in London than what I can enumerate – there is almost everything for everyone to see, smell, taste, hear, touch and enjoy. That`s the magic of London!)

However, living in London comes with its own downsides: especially the high costs of accommodation and transport. Food is surprisingly affordable!

Life after Birkbeck

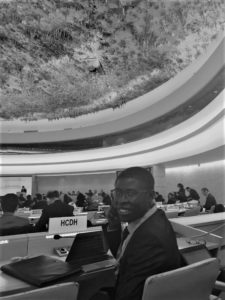

It was sad saying goodbye to my community of friends and networks when my studies concluded. After completing my studies at Birkbeck, I was offered a scholarship by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Finland to study on an intensive postgraduate international human rights course at the Institute for Human Rights, Åbo Akademi University. Upon the completion of the course in Finland, I was an Intern at the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Geneva, Switzerland. Later I worked as a Legal Intern at the World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters in Geneva. The experiences and illuminations I gained from these intergovernmental organisations are invaluable! I am a strong believer, follower and advocate that,

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

Currently, I am writing a research paper for journal publication, as I keenly continue to follow my career goals, and seek to contribute, no matter how tiny, to improving the wellbeing of our common humanity, without prejudice or discrimination. Indeed, as it has been said before as human beings, we are all as weak as the weakest link (other human being whose rights are not respected, protected and promoted) living among us in our society. My study at Birkbeck (through its critical review approach) and experience at the United Nations has made me see this reality clearer than never before.

What advice would you give other people thinking of studying at Birkbeck?

I highly recommend Birkbeck, University of London! You will study at a university that is known for research excellence with renowned academics; you will study in a supportive environment, with quality teaching; at the end of your studies you will graduate with a prestigious University of London qualification, and not forgetting you will become a Birbeckian; and at the end of your studies you will not look at the world the same way!

As for me, studying for a PhD at Birkbeck is one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life, and I am a very proud Birbeckian alma mater.