Richard Clark, Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Politics, writes about how Birkbeck is woven into the very framework of the capital city. This blog is a part of a series that celebrates Birkbeck’s 200th anniversary in 2023.

Unlike paper maps, smartphone navigation will tell you how to get there but not what’s around you. But search through the index of an old ‘A to Z’ map of London and if your destination starts with ‘B’, you’ll probably be surprised to notice quite a few ‘Birkbeck’ place-names.

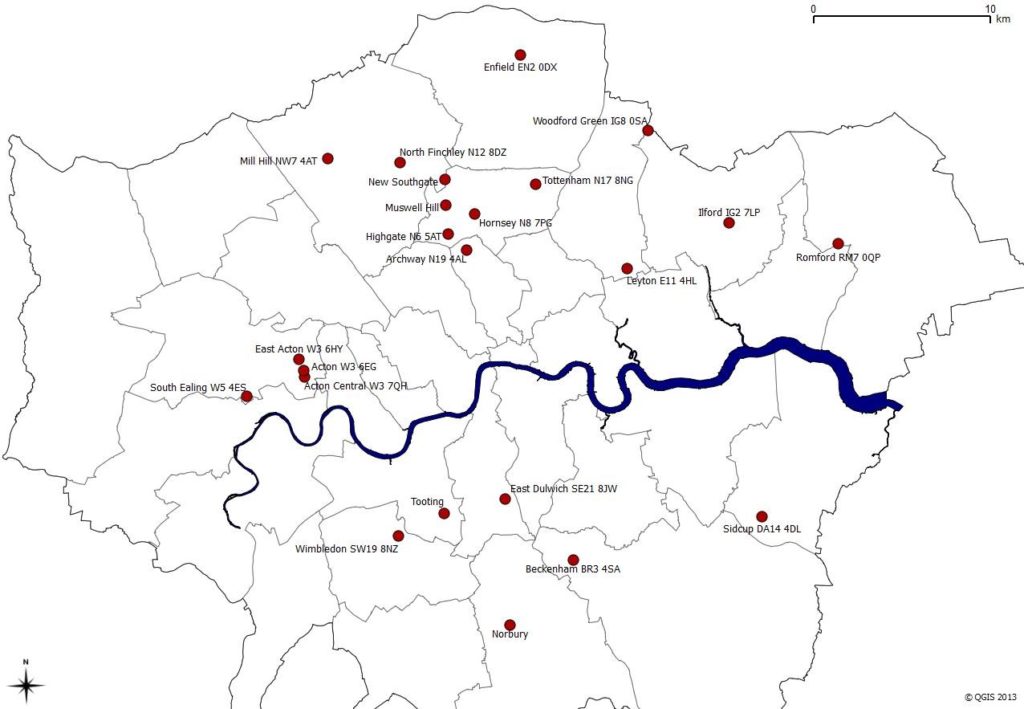

Birkbeck roads survive today in Hornsey N8, in Finchley N12, in Tottenham N17 and in Mill Hill NW7. There are more in Ealing W5, and in Wimbledon SW7and Acton W3. Acton also has a Birkbeck Mews, and there is a Birkbeck Grove in leafy Acton Park. Dulwich SE21 has a Birkbeck Hill and a Birkbeck Place and the pub-like building where they join was once precisely that – the Birkbeck Tavern. In east London, Bethnal Green E2 has a Birkbeck Street, Dalston E8 has a Birkbeck Road (as well as another Birkbeck Mews) and Leyton E11 has two Birkbeck Roads, North and South, as well as another Birkbeck Tavern – still a lively pub protected by its patrons who saved it from redevelopment by a campaigning ‘Birkfest’.

Outside the London postcode area, there are yet more Birkbeck roads — in Beckenham, in Brentwood, in Enfield, in Ilford, in Romford and in Sidcup. There’s a Birkbeck Gardens in Woodford and a Birkbeck Avenue and a Birkbeck Way in Greenford. Beckenham has its Birkbeck Station (established as Birkbeck Halt in 1858).

More Birkbeck place names can be found on old maps and census records of the London area. For example Birkbeck Road, Birkbeck Place and Birkbeck Terrace in Streatham, Wandsworth, are recorded in the 1881 and 1891 census but have subsequently been lost as have Birkbeck Road and Birkbeck Place, Camberwell which appear also in the censuses of 1871. Elthorne Road in Archway N19 started life as Birkbeck Road as did Holmesdale Road in Highgate N6. Both had Birkbeck Taverns – the former is now converted into ‘Birkbeck Flats’ (but still, like the Dulwich Tavern, recognisably an old pub). The Boogaloo at the top of Holmesdale Road is still a pub — a lively music and comedy venue, well worth a visit, with a ‘Birkbeck’ mosaic (desperately in need of protection) testifying to its past still on the threshold as you enter.

All the above have a close connection with Birkbeck, University of London, and reveal something of the College’s past. Greenford’s Birkbeck Avenue and Way are the most recent. Both are named after what used to be the Birkbeck College Sports Ground, leased to the College by the City Parochial Foundation from the 1920s until 1998 when governors felt they could no longer justify the rent. Today’s lessee is the London Marathon Charitable Trust and the ground’s football, rugby and cricket pitches serve clubs across West London.

Several of the Birkbeck toponyms – for example those in Bethnal Green, in Dalston and in Camberwell — are associated with the Birkbeck Schools, established by William Ellis between 1848 and the early 1860s. Ellis was one of the founders and benefactors of Birkbeck College’s predecessor, the London Mechanic’s Institute —his name appears on a foundation stone in the lobby of the Malet Street entrance. One Birkbeck School building — today Colvestone Primary School in Dalston — still stands, its structure (including well-lit classrooms in place of dull monitorial halls) reflecting what for the time were Ellis’s progressive educational theories. The schools were set up to teach children ‘social economy’ as an antidote to the radical socialist ‘political economy’ then gaining ground in Europe and they prefigured the civics curricula taught in English schools today.

Most of the other toponyms mark the locations of ‘Birkbeck Estates’ – land purchased and developed by the Birkbeck Land and Building Societies established in the premises of the London Mechanics Institute by Francis Ravenscroft in 1851. Ravenscroft had joined the LMI as a student a couple of years previously, became a Governor, and set up the Building Society as a ‘penny savings bank’ to encourage thrift and diligence amongst its students, offering them the prospect of a house – and (for the men) a vote. Initially based in a cupboard in the LMI’s office, the Societies grew to become a major bank, taking over the LMI’s premises and financing its move —as the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution — to new premises nearby. Without Ravenscroft (his bust sits on a windowsill in the Council Room) Birkbeck College would probably not exist today. The estates played a significant role in the suburbanisation of London and are interesting for many reasons – not least because, unlike the temperance building societies of the period, they featured pubs.

For more on the story of the Birkbeck Bank and Building Society, watch out for a subsequent blog or have a look here. And there’s some information on the Birkbeck Boozers here. I’m about to submit a paper on the Birkbeck Schools, and perhaps I’ll blog a little later about these too.

Further information: