This post was contributed by Ben Worthy, lecturer in Birkbeck’s Department of Politics. It was originally posted on May 11 at The Conversation

David Cameron’s 2015 election victory is all the more powerful for being almost completely unexpected. But as the euphoria dissipates, the obstacles in his path are coming into focus. Above all, he faces two tricky and complex problems: the promised EU referendum and future arrangements with Scotland (and by extension, the other parts of the UK).

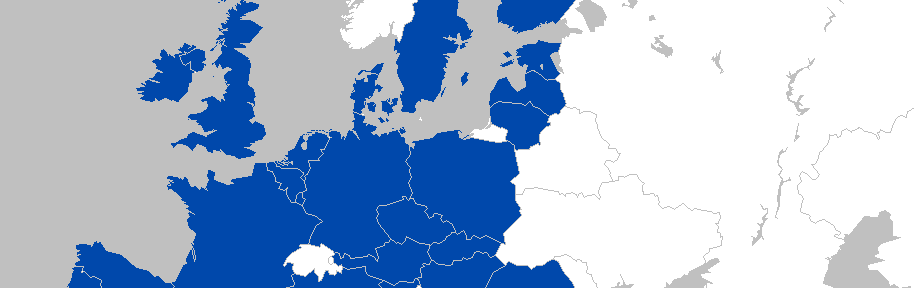

The EU referendum was in large part a gamble to see off UKIP and settle his party, but now he looks likely to do it as soon as possible, perhaps even in 2016, banking on a status quo bias to keep us in. And on Scotland, he has committed to implement further devolution and push through the jointly agreed Smith Commission proposals. In both cases, the devil’s in the detail.

On the EU, lots of the specifics are unclear. We don’t yet know what the question on the referendum ballot might be, or what “reforms” to the EU will convince us to stay – and the coming struggles over them promises to be vicious.

On Scotland, it is about giving the new SNP stronghold “the strongest devolved government in the world” – but there will be a need, as Nicola Sturgeon put it, to discuss these issues in more detail (and ditto for Wales). Devolution may also flow back into the Europe debate – Cameron has already refused a separate EU referendum for Scotland but could he hold that line?

On both these pressing matters, Cameron is up against assorted bodies and people who could make his life harder. They can all be dealt with separately, but if they join forces, they could drain Cameron’s political energy and time – the two things a prime minster can least afford to lose.

Houses divided

Cameron’s majority is 12 (or actually eight or 16, as Colin Talbot points out. This is far better than most expected, but it depends on the solidarity of an increasingly rebellious party.

The trouble for Cameron is that parliamentary rebellion is habit-forming: the more you rebel more likely you are to do it again in the future. And the last parliament was the most rebellious since 1945 (here are its top seven rebellions against him).

This bad news gets worse: the two biggest issues that Conservatives rebelled over were constitutional matters and Europe – the two most urgent problems for the next five years. Party management and discipline will be crucial, but even that may not stave off problems if Cameron’s majority is whittled away over time. Just ask John Major, whose 22-seat advantage in 1992 withered to zero by the end of 1996.

The new block of 56 SNP MPs has limited practical power in the Commons, but its members can still use their electoral dominance and high media profile to keep Scotland high up the agenda. And in the event of a Tory rebellion, or a vanishing majority, the opposition parties’ ability to co-ordinate could determine Cameron’s room for manoeuvre.

Don’t forget the House of Lords

The House of Lords is often overlooked, but its potential power to delay and disrupt a government agenda is great – and growing. As Meg Russell demonstrated, since 1999 the Lords has clearly started to feel more legitimate and more prepared to defeat the government: its members did so 11 times in 2014-2015 and 14 times in 2013-14.

The Conservatives are now heavily outgunned in the House of Lords, with 224 peers facing off against 214 Labour ones, and 101 (presumably livid) Liberal Democrats and 174 cross-benchers.

The Lords will be duty-bound to pass an EU referendum bill due to the Salisbury Convention, which means the Lords have to pass manifesto policies. However, there are plenty of other venues for lawmakers to vent their anger or disrupt the government’s timetable for other parts of its reform programme. Select committees in both the Lords and Commons expressed concerns at the lack of consultation on the Smith proposals, boding ill for the constitutional arguments ahead. Concern in one house triggers worries in the other, so wherever it crops up, Cameron will need to take it seriously.

Outside parliament, it remains to be seen whether the eurosceptic right-wing media will be satisfied with any concessions or reforms Cameron gets from Brussels. It may prefer to give the oxygen of publicity to the SNP (particularly the very media-savvy Salmond) and treat us to a long and fascinating Cameron-vs-Sturgeon battle royale.

Cameron also invoked English nationalism in the election campaign, going so far as to launch an England-only manifesto, but it remains to be seen if he can channel and control the mounting pro-English clamour in the right-wing press over the coming months while simultaneously making concessions to Europe or Scotland.

Circling vultures

Behind Cameron are a number of senior Conservatives with at least semi-public leadership ambitions. He’ll have to manage them with precision. In the almost certain event of an EU referendum, he would have to make a very tough choice: whether to ask all ministers to all support staying in, or as Harold Wilson did in the 1975 referendum, to let everyone temporarily agree to disagree.

Equally, there’s no knowing how Cameron’s discontents and potential rivals might react to new devolution settlements. Perhaps the future leadership contenders are already plotting to court English nationalism for party and media favour.

Cameron’s leadership capital is high for the time being, but with so little room for division, his promise to step down by the 2020 election may come back to haunt him. As he seeks to deal with the “Scottish lion” and slay the EU dragon – or at least negotiate with it – everything could get complicated and intensely political very quickly. And the chances of success (whatever that is) are almost impossible to gauge.