As part of Science Week 2017, Dr Emma Meaburn from the Department of Psychological Sciences at Birkbeck gives an insight into a day in the life of a scientist.

I get up at … 6am (or 6.30 am, if I am lucky), when I am woken by my children. The next two hours are a whirl of breakfast, loudness, finding lost shoes, cajoling, cuddles and probably some light bribery before I leave the house at 8.15am. I drop the youngest child off at nursery on my way to the train station, and typically arrive at Birkbeck by about 9.30am.

My research … looks at the genetic contributions to individual differences in psychological traits and disorders. We all differ, and I am interested in how these differences are influenced by differences in our DNA and how the information stored in our DNA is used.

I teach on … the BSc Psychology degree program, where I co-convene and co-teach a large first year ‘Research Methods’ module that provides psychology students with a basic grounding in the principles of experimental design and statistics. Undergraduate students can sometimes be surprised that research methods form a core element of the program, and we work hard to make it accessible and relevant to the students’ current knowledge and career aspirations. I also teach on the final year “Genetics and Psychology” optional module. This is always enjoyable as I get to talk about my own research findings and that of my colleagues, and expose the students to the newest methods and insights from the field of behavior genetics.

I am also responsible for … quite a few things! Broadly, my job falls into three categories; research, teaching and service. As part of my research activities I am responsible for running a lab and the admin that comes with it; writing ethics applications; PhD student supervision, training and mentorship; securing funding (writing and revising grant applications); dissemination of my research via conference attendance, giving invited talks, publishing my work in peer reviewed articles and public engagement activities. Behavior genetics is a fast-paced field, and I stay informed about new developments and methods as best I can by reading the literature, speaking to colleagues and collaborators, organizing and attending conferences and (occasionally) training workshops.

When I’m teaching, I will be lecturing (typically on two evenings per week); developing or updating content for modules (slides, worksheets and notes); marking assessed work; writing exam papers; writing model answers; supervising teaching assistants; answering student emails; writing letters of recommendation; designing lab experiments; acting as a personal tutor for undergraduates (roughly 10-15 students); attending exam board and module convener meetings; and being assessed on my teaching.

I also peer review grants and manuscripts; supervise undergraduate (about four per year) and graduate student research projects (about two per year); sit on the academic advisory board and postgraduate research committee, and I am a member of the management committee of the University of London Centre for Educational Neuroscience, which provides a unified research environment for translational neuroscience.

…or I do none of the above because nursery have called and my child has a temperature, and I have to go and collect him (three out of five days last week!)

My typical day … doesn’t really exist! One of the best aspects of academic life is that each day is different.

If I am teaching in the evening, typically I will meet with my PhD students (or project students) in the morning where we discuss the past week’s progress, go over new results and edits of conference abstracts and manuscript drafts. Then there is at least an hour of email and admin tasks such as paying invoices, tracking lost lab orders, or hurriedly writing a PhD application, before heading to the gym for an hour of ‘me’ time. I’ll then undo all my hard work by grabbing a hearty lunch from one of the many fantastic food places around Birkbeck, before attending a departmental seminar or journal club. That leaves me with a couple more hours to squeeze in research and research admin before preparing for the evening’s class. Once the class is over (at about 8.30pm), I head back to my office for 30 minutes of emails before catching the tube home. All being well, I’ll get home around 9.30/10pm, check on my (mostly) sleeping family, and do 30 minutes of life chores before collapsing into bed.

I became a scientist… because I had always loved science and by my late teens I had developed a keen interest in what was then known as the “Nature Versus Nurture’ debate. I think this interest was sparked by my own experiences and reflections as a fostered child (I was separated from my biological parents at six months of age), and when I finally studied genetics as an undergraduate student in human biology at King’s College London, my mind was made up – I was going to be a geneticist!

My greatest professional achievement… has been establishing myself as a research active academic and developing my own research program, in a field where academic positions at renowned institutions like Birkbeck are few and far between and competition is fierce. I get to work in a research field that is dynamic, challenging and interesting, and in a supportive, autonomous and friendly environment.

Since the development of penicillin as a treatment for bacterial infections in the 1940s, antibiotics have played an integral role in modern medicine. Beyond their obvious utility in treating serious diseases like tuberculosis and pneumonia, antibiotics have facilitated a vast array of modern surgical treatments. Without them, major procedures from organ transplants to hip replacements and cancer chemotherapy would carry too great a risk of infection to be feasible. Antibiotics have become so deeply woven into the fabric of modern life that a future without them borders on the unimaginable.

Since the development of penicillin as a treatment for bacterial infections in the 1940s, antibiotics have played an integral role in modern medicine. Beyond their obvious utility in treating serious diseases like tuberculosis and pneumonia, antibiotics have facilitated a vast array of modern surgical treatments. Without them, major procedures from organ transplants to hip replacements and cancer chemotherapy would carry too great a risk of infection to be feasible. Antibiotics have become so deeply woven into the fabric of modern life that a future without them borders on the unimaginable. It’s an unusual position for an organisation to find itself in: on the brink of its third century and still no signature style. Imagine Apple without its elegant designs and simple use of space; or Google minus its primary-colours and clean white canvas.

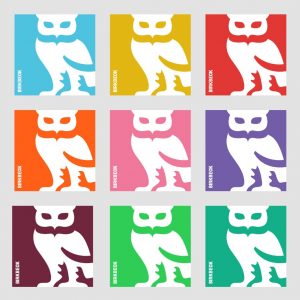

It’s an unusual position for an organisation to find itself in: on the brink of its third century and still no signature style. Imagine Apple without its elegant designs and simple use of space; or Google minus its primary-colours and clean white canvas. The challenge, then, was to create an identity – typefaces, colour palette, ways of presenting information – that would live happily alongside the lockup and work across digital and printed channels and products for years to come.

The challenge, then, was to create an identity – typefaces, colour palette, ways of presenting information – that would live happily alongside the lockup and work across digital and printed channels and products for years to come. There is enough flexibility to give people across the university room to ‘play’ with the identity, for instance by an unrestricted colourful palette and playful new ways of using our crest’s iconic owl – signifying our evening study. But brief, user-friendly guidelines gently help people stay within a ‘safe space’, ensuring Birkbeck always looks the part.

There is enough flexibility to give people across the university room to ‘play’ with the identity, for instance by an unrestricted colourful palette and playful new ways of using our crest’s iconic owl – signifying our evening study. But brief, user-friendly guidelines gently help people stay within a ‘safe space’, ensuring Birkbeck always looks the part.