This article was contributed by Dr Ben Worthy, a lecturer in Birkbeck’s Department of Politics. It was originally published on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

This article was contributed by Dr Ben Worthy, a lecturer in Birkbeck’s Department of Politics. It was originally published on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

Jack Straw and Malcolm Rifkind, two senior MPs were snared in a sting by the Telegraph in which they appeared to offer access for cash. The Labour Party leader, Ed Miliband has responded by calling for stringent new limits on MPs extra earnings and work. In this article, Ben Worthy investigates the practicalities of Miliband’s proposals and asks whether they will increase trust in MPs among the public.

In the wake of the latest ‘Cash for Access’ revelation, Ed Miliband has committed to limit MPs’ outside earnings to £10,000 per year and introduce a ban on all second jobs. The Labour party will start tomorrow, using its opposition day to propose a bill on the subject. These proposals fit with a series of steps since the 1990s designed to open up and regulate this area as controversy has grown about extra earnings and work. But how will these latest changes impact on MPs and the public?

In terms of MPs, the two issues are whether the new proposals will be implemented and whether they will work. Implementing a ‘cap’ and (eventual) ban on outside earnings would represent an easy win for a new Labour government in 2015, a symbolic step that would have ‘signalling effect’ for the new government’s attitude towards such behaviour. On a more partisan level, it will hit Conservatives much harder than Labour. Research by the Guardian indicates that this would impact on 63, or 1 in 5, Conservative MPs who currently earn over £63,000 as against only 20, or 1 in 12, Labour MPs. You can see more numbers from the Telegraph here.

However, it all may depend on whether Ed Miliband has the numbers in the new House and what politics exists around the change. As Meg Russell pointed out, a number of things need to align for any reform of Parliament to happen – a mixture of a relevant crisis, political will and the right context. Remember David Cameron’s cutting down of the House of Commons to 600 MPs?

The second question for MPs is whether it will work. The reforms are part of a longer trajectory of change towards regulation and transparency. The danger of is that such change can drive poor activity into hard to reach places, away from publicity and into dark corners. It could also trigger other unwanted debate, such as around what MPs do with their time or, more disturbingly, Members getting a pay rise – new Prime Minister Miliband is not likely to want to propose bumping up salaries to £150,000.

What of the public? The new proposals are designed to help increase trust and put an end to lobbying scandals. One basic question is whether the public will notice. It is claimed that few even know the name of their MP, though recent research has challenged this. The public does support a complete ban on second jobs (see page 6 of this polling) and, as research by Rosie Campbell and Philip Cowley shows, they do not approve of wealthy MPs, objecting to both the ‘sums and the source’, with a particular dislike of directorships. Their experiment concluded that any sum of money earned while an MP, whether above or below the cap, is problematic.

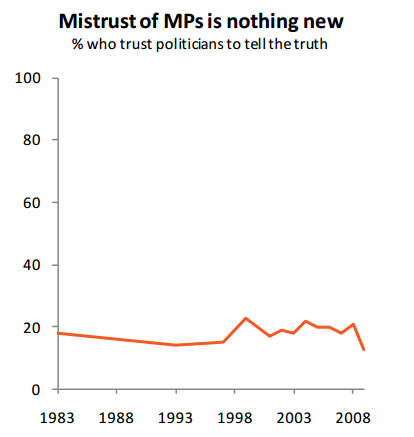

Whether this will then increase public trust is a far bigger and more complex question. It may reduce the space or room for manoeuvre in this one area. However, hopes of ‘improving trust’ over-simplify how we think and process information – the MPs’ expenses scandal ‘confirmed’ to many that MPs were corrupt rather than ‘revealed’ it to them. Voters generally suffer from a negativity bias and the continual string of ‘cash for…’ revelations are likely to have fed already deeply held views about UK politics. Nor will it end other sources of Parliamentary controversy, from the revolving door to the picking of leaves. So while it may help change behaviour, looking at the graph below, it appears unlikely any one thing can dramatically improve trust in MPs.