By Joanna Bourke, Professor Emerita of History, Birkbeck, University of London and author of ‘Birkbeck: 200 Years of Radical Learning for Working People’ (Oxford University Press, 2023)

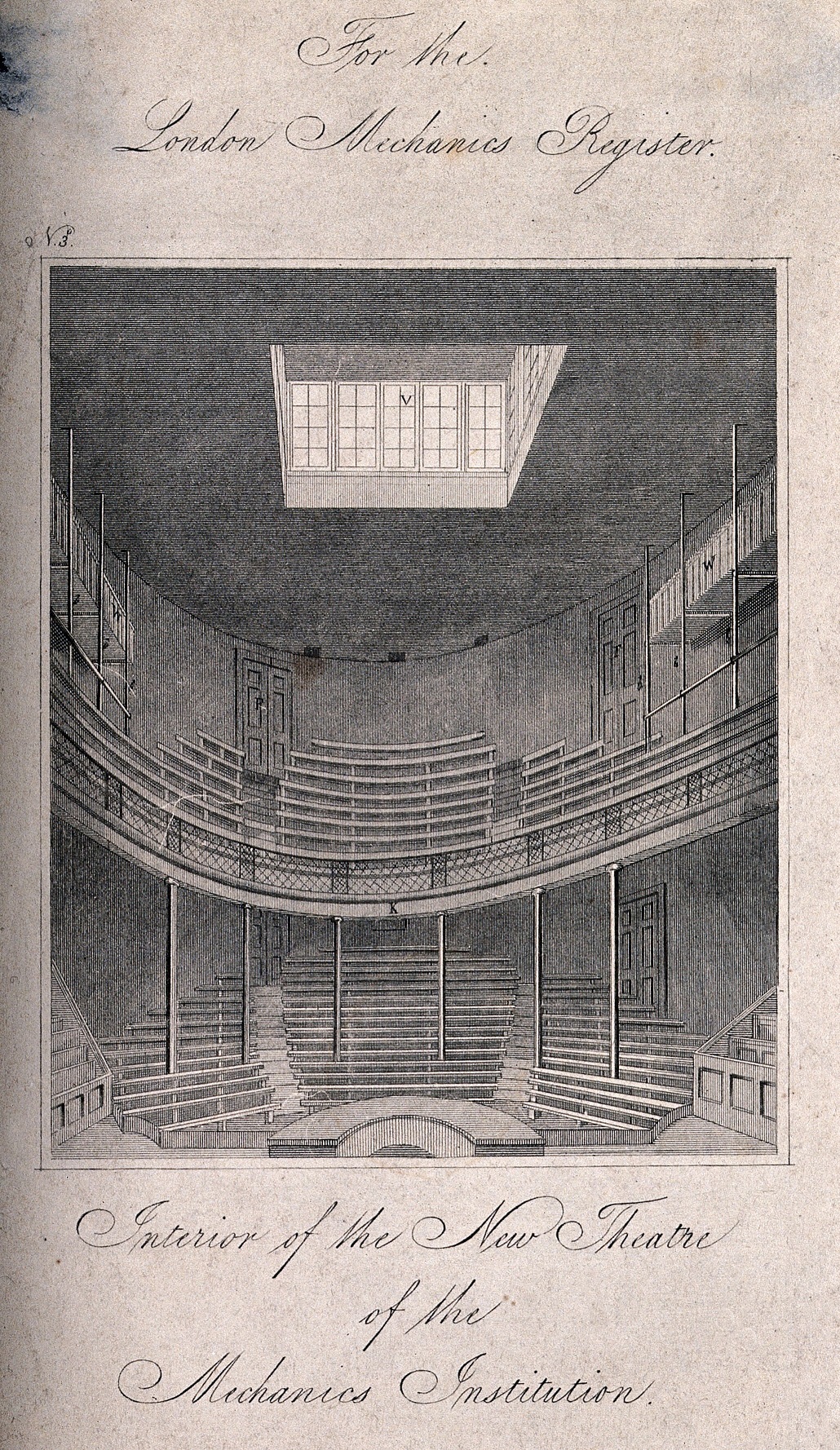

London Mechanics’ Institute, Southampton Buildings, Holborn: the interior of the lecture theatre. Engraving, 1825. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/w8t6sedz

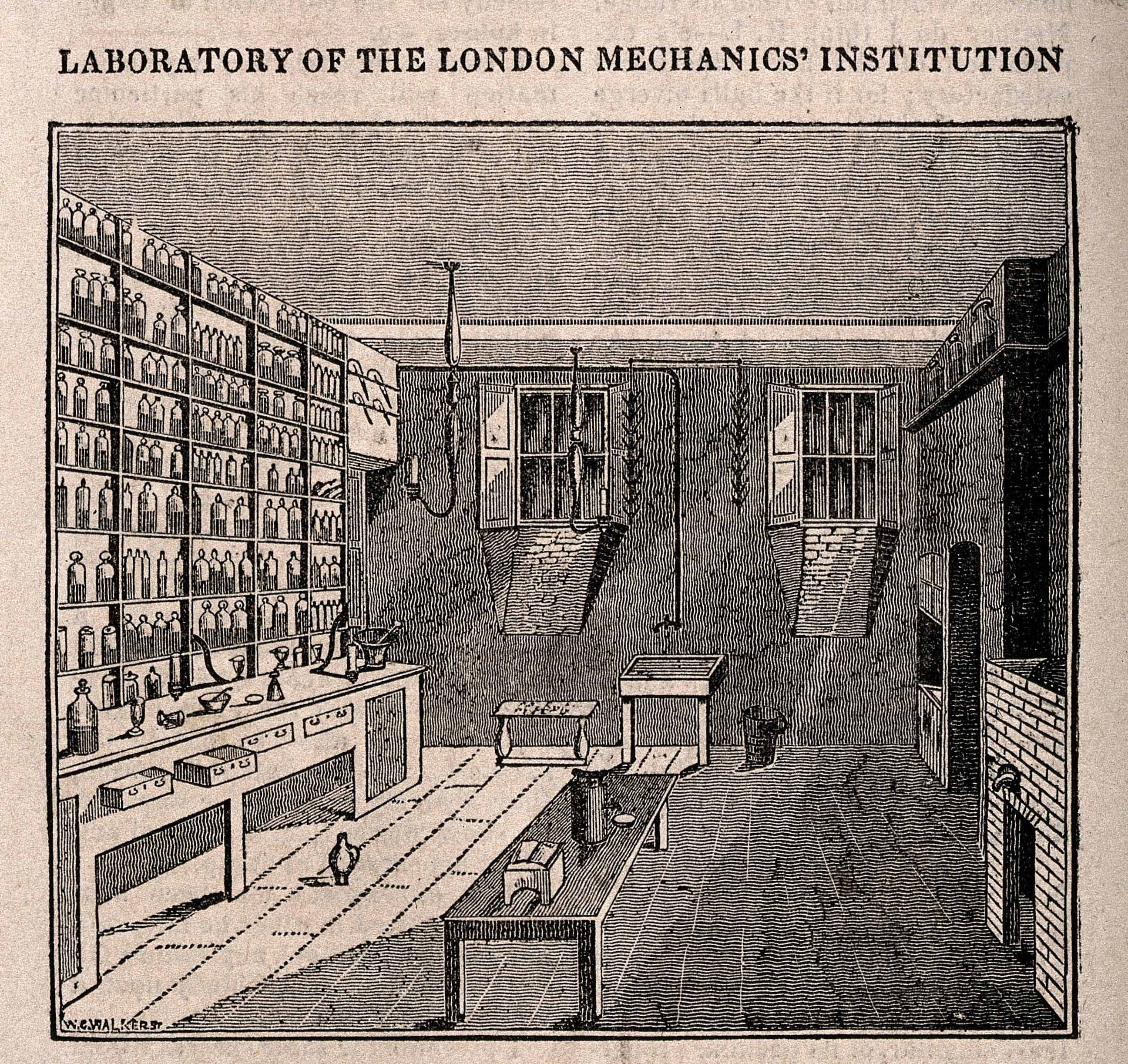

When Birkbeck was established in 1823, it was called the London Mechanics’ Institution. It was one of the first ‘mechanics’ institutes’ in the world and, like many others, was animated by the idea that working people should be given the opportunity to expand their intellectual horizons. The mechanics’ institutes also believed in the importance of ‘useful knowledge’ and the role of education in fulfilling not only people’s intellectual qualities but their moral and spiritual ones as well.

The 1820s had been a period of rapid growth in the number and popularity of mechanics’ institutes. Although classes for the education of working people had been founded sporadically since the eighteenth century (most notably, this included Joseph Middleton’s Spitalfields Mathematics Society which taught scientific subjects to artisans and craftsmen from 1717), the systematic establishment of mechanics institutes is often credited to physician and philanthropist George Birkbeck. In 1799, he had been invited to teach ‘natural philosophy and chemistry’ at the Andersonian Institution, which had been founded three years earlier under the will of John Anderson, former Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. Needing a particular machine for his classes, Birkbeck had visited a mechanical workshop and was struck, first, by the workmen’s ignorance of basic engineering facts and, second, by their hunger for knowledge. He promptly opened his classes to mechanics, offering classes on Saturday evenings. Birkbeck’s aim was to ensure that a workingman would ‘cease to be a mere machine, toiling on from day to day’ but would ‘understand the laws on which his operations were based’ and therefore ‘perfect himself in his calling’.[1] Demand was high; by the fourth class, there were 500 men in attendance.

George Birkbeck left Glasgow for London in 1804, where he set up a fashionable medical practice, in addition to working as a physician to the General Dispensary for the Relief of the Poor in Aldersgate Street, which provided home-visiting and outpatient treatment for paupers and working-class men and women in that area of London. Birkbeck was also active in the Medical and Chirurgical Society, the Chemical Society, the Meteorological Society, and the London Institution, established in 1809 for the diffusion of science, literature, and the arts. It was during this stage in his life that he forged friendships with radicals and economists including Ricardo Hume, John Hume, William Cobbett, Jeremy Bentham, George Grote, James Mill, and John Stuart Mill. Within this milieu, George Birkbeck was well placed to throw his energies into a wide variety of social causes, including support for the Reform Act of 1832, which transformed the electoral system, and the fight to repeal the duty on paper and the tax on newspapers, which was severely limiting the ability of people to contribute to political debate and disseminate knowledge. In 1823, when patent agent Joseph Clinton Robertson and economic Thomas Hodgskin (both of the Mechanics’ Magazine), along with the ‘radical tailor’ Francis Place, put out a call for the establishment of a London Mechanics’ Institution, George Birkbeck was considered the ideal President. It was the start of what would become an international movement. By the middle of the nineteenth century, there were an estimated 610 mechanics institutes in England, 55 in Scotland, 25 in Ireland, and 12 in Wales.[2] Institutes were also flourishing in the U.S., Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere.

These institutes claimed to address the educative needs of ‘mechanics’, but this term was used much more widely than it is today. Although most mechanics’ institutes were established with the support of local dignitaries and philanthropists, the majority of ‘members’ (they were called ‘students’ much later) called themselves ‘operatives’ or ‘members of the working class’. They were not ‘labouring poor’. There were heated debates about who should wield power within the institutes. In one article, published in 1826 and entitled ‘To the Members and Managers of the Mechanics’ Institutions in Britain and Ireland’, the anonymous author insisted that the ‘operative classes… for whose exclusive benefit all Mechanics’ Institutions profess to be instituted’ (emphasis in the original) must retain control. The author admitted that the employers of the operative classes, as well as others of the benevolent rich, have in many places come forward with their money, books, and instruments, to aid in the establishment of your institutions. Such is one of the best modes of promoting mutual kindness between the rich and the productive classes. But let not this class of person expect power in return for their gifts. By so doing they would have made sordid bargains instead of gifts, and would nullify all those claims to beneficence and sympathy, which would be otherwise their natural and sufficient reward.[3]

However, as the century progressed, the proportion of members who ‘worked with their hands’ declined: the classes were increasingly populated by clerks, shopkeepers, and teachers, for example. This shift in membership led to a broadening of the curriculum. Technical and scientific subjects remained important, but more literary, historical, and arts-based classes also proved popular. As statesman, orator, and poet George Howard (the 7th Earl of Carlisle) quipped in his address to the Manchester Mechanics’ Institute in 1858, while mechanical, engineering, and other scientific pursuits were being taught, they were being supplemented with classes in ‘music, dancing, drawing, modelling, French and even millinery – no doubt an important pursuit in its way – (laughter)’. Howard’s banter and the laughter that followed was a wry reflection of the unease surrounding the education needs of the female members of institutes throughout the UK and the world.

The involvement of women in the mechanics’ movement was a source of anxiety in the early decades. On the one hand, would the presence of women in the institutes lead to immortality, as un-chaperoned women mingled with men in the same halls? Would it enhance competition for books and lecture-space? Would the ‘scientific’ quality of the lectures be diluted, since it was feared that women might demand more leisure-orientated classes such as art and music? On the other hand, would educating working women enhance their employment opportunities (for example, as teachers of art and music)? Would it promote more fulfilling and equitable relationships? As early as 1826, prominent Owenite William Thompson pleaded with the mechanics’ institutes to let your libraries, your models, and your lectures… be equally open to both sexes. Equal justice demands it…. Long have the rich excluded the poorer classes from knowledge; will the poor classes now exercise the same odious power to gratify the same anti-social propensity – the love of domination over the physically weaker half of their race?[4]

It was a point echoed by radical politician Rowland Detrosier in 1831. Detrosier had founded the New Mechanics’ Institution, a break-away from the Manchester Mechanics’ Institute, and he believed that the education of women had to be central to working-class emancipation. He argued that it was necessary to ‘raise the females of the working classes from the state of degradation’ in order to make them ‘rational companions of men’. By providing working-class women with education, their menfolk would be encouraged to turn away from ‘immorality and crime’.[5] Educated woman would raise rational children; their domestic labour would enhance families, communities, and the entire nation. In Detrosier’s words, ‘individual reform will secure national happiness’.[6]

For liberal as well as radical educationalist, the lodestone was ‘useful knowledge’. No-one promoted this theme more effectively than Henry Brougham, one of the main promoters of the London Mechanics’ Institution. Brougham was a lawyer by profession, but he came to public notice because of his role as chief adviser to Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of King George IV. By the 1830s, Brougham was Lord Chancellor of Great Britain, where he was an active supporter of the 1832 Reform Act and, as an active abolitionist, the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. In 1826, he founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Crucially, however, his book on education was a popular success. Entitled Practical Observations Upon the Education of the People. Addressed to the Working Classes and their Employers (1825), it became the “Bible” for the mechanics’ institutes everywhere. In its first year alone, Practical Observations went through nineteen editions.[7] According to one admirer, not since ‘the Scriptures were first printed and circulated in the common tongue’ had there been such an important text.[8] In Practical Observations, Brougham contended that only ‘tyrants’ and other ‘bad rulers’ should be terrified by ‘the progress of knowledge among the mass of mankind’.[9] He maintained that ‘the time is past and gone when bigots could persuade mankind that the lights of philosophy’ were ‘dangerous to religion’. He argued that the ‘peace of the country, and the stability of the government, could not be more effectually secured than by the universal diffusion’ of knowledge about the ‘true principles and mutual relations of population and wages’.[10]

Brougham’s 1825 book was a milestone, in large part because the mechanics’ institutes were faced with exceptionally high levels of hostility at the time. Opponents had four major concerns. The first was that educating working people would be detrimental to good morals. John Dunlop, a Scottish Justice of the Peace maintained that a ‘literary and scientific education’ would not ‘generate that change of heart required in Scripture’, nor would it ‘advance morality to a sublime and scriptural pitch’.[11] He was especially worried about how education could be ‘beneficial to morality’ for female members.[12] Scottish essayist and episcopalian priest Archibald Alison expressed similar sentiments in more vivid terms. In 1838, he argued that educating working men would give them ‘the means of the gratification of the animal or the sensual propensity’.[13] He also advocated for censorship in the books made available to working people. He contended that education that was ‘unaccompanied… by any adequate restriction upon the books [workers] read or any adequate religious instruction’ was a ‘very great cause of the depravity of the times’.[14] Alison agreed with philosopher Francis Bacon that ‘knowledge or education is power’ but it could be the power to do mischief as well as good.[15] In his book The Social Condition and Education of the People in England and Europe (1850), Joseph Kay summarised this position when he observed that a spirit omnipotent for evil, a spirit of revolution, irreverence, irreligious, and recklessness, and, more dangerous of them all, a spirit of unchecked, unguided, and licentious intelligence is abroad, which will be the most dangerous enemy, with which Christianity had hitherto had to cope.[16]

The second, related concern expressed by opponents of the mechanics’ institutes is that they were a threat to the religious monopoly over education. Churchmen and their supporters feared that any education that was primarily ‘scientific and philosophical’ rather than ‘moral and religious’ was risky, as conservative, Anglican Biblical scholar Edward William Grinfield warned in 1825.[17] Grinfield believed that it would be far better that the common people of this country should remain totally illiterate, than they should thus be furnished with tools by which they would inevitably work out their own and the public ruin.[18]

Like Alison, Grinfield wanted to know who was going to be responsible for choosing what books working men would be reading in mechanics’ institutes. He believed that it was ‘desirable that the choice of such books should be left to those whose superior knowledge may enable them to direct the reading of others’.[19] It was ‘folly’ to educate people beyond what they needed to know, especially when such knowledge would not make a working man ‘more happy in that station to which Providence had called him’.[20] Grinfield urged the ‘upper classes of society’ to

do every thing in your power to give the labouring orders a religious, virtuous, and useful education, by founding this education on the love and the fear of God, and by associating it with a strong attachment to the existing institutions of our country.[21]

It was a very different use of the idea of ‘useful’ to the one promoted by people such as Brougham and Birkbeck. For Grinfield, ‘useful’ meant ensuring the maintenance of social hierarchies. He addressed working people directly, advising them to remember that knowledge is valuable only as it is connected with an advancement in piety and religion; that sobriety and contentment are far more valuable qualifications than any attainments in mere art or science; and that those who would confine your education exclusively to the purposes of the present life and no real friends to your happiness and welfare.[22]

Theological concerns were augmented by more practical ones. The third and fourth anxieties related to the establishment of mechanics’ institutes is that they would ferment social and political disorder. Some commentators alleged that there was a link between education and crime. A ‘comparatively better education was co-existent with a greater amount of crime’, claimed John Dunlop (a Scottish Justice of the Peace) speaking before the 1834 Select Committee on Drunkenness. If evidence was needed, he urged the commissioners to look at France.[23] Archibald Alison (a Scottish essayist and episcopalian priest) made a similar argument before the Select Committee on ‘Combinations of Workmen” (that is, trade unions). He claimed that a statistical analysis of 83 departments in France revealed that ‘the amount of crime is just in proportion to the quantity of intelligence that prevails; that crime is invariably the greatest in those departments where there is most knowledge and education, and invariably the least in the reverse’.[24]

The possibility that educated working people would incite social disruption, however, paled alongside the threat of political chaos. Of all the arguments against mechanics’ institutes, this was the most vocal. For Moses Angel, who was active in the Jews’ Free School, the mechanics’ institutes were an improvement on ‘the tavern, the billiard-room, the cheap theatre, and the casino’ because they at least attempted to encourage ‘the cultivation of the mind’. However, they also risked turning ‘half-educated men into ill-formed politicians (and therefore, generally revolutionists, or at least democrats)’.[25] For Angel, democracy was as dangerous to social stability as all-out revolution. This was also what Orthodox Chief Rabbi of the Empire Nathan Marcus Adler argued, although he framed it more broadly by musing that members of the institutes were turned into ‘dreamers, talkers, and vague reasoners’.[26] One critic even contended that educating working men was as perilous as educating animals. ‘Suppose’, this anonymous author in Edinburgh Review wrote in 1826, that ‘some friend to humanity were to attempt to improve the condition of the beasts of the field; – to teach the horse his power, and the cow her value’. Wouldn’t that make the animal less ‘tractable and useful’ and not ‘so profuse of her treasures’ (that is, milk) ‘to a helpless child?’[27] Once again, ‘useful knowledge’ was equated with knowledge that maintained the status quo rather than questioned it. It was linked to anxieties about weakening deference of the ‘lower orders’ towards their ‘superiors’. In the words of an author writing in 1825 in the St. James’s Chronicle, ‘every step which they take in setting up the labourers as a separate and independent class’ was a step towards destruction: ‘A scheme more completely adapted for the destruction of this empire could not have been invented by the author of evil [that is, the devil] itself.’ The Rev. George Wright, vicar of Askham Bryan, in Mischiefs Exposed (1926) expressed this view succinctly, warning that the institutes were guaranteed to ‘degenerate into Jacobin clubs, and become nurseries of disaffection’.[28]

This barrage of hostility towards mechanics’ institutes and other educational organisations catering to working people failed to dent the momentum of reform. After all, the institutes were part of a much larger movement within politics at the time. The early nineteenth century was a time of intense political and economic reform. Civic society itself was undergoing revolutionary change. Industrialization was transforming relationships between the different classes. Even the most conservative employer was beginning to recognise the need for more literate and educated workers if their businesses were to flourish. This was especially the case in large industrial centres where the economy was dependent on the skills of its workers. Economic competition, especially from continental Europe, was a concern. Was the U.K. falling behind? Governments were tackling elementary education (especially after the Education Act of 1870); providing compulsory education and progressively raising the age at which children were required to attend school. The instruction given in mechanics’ institutes were a useful supplement.

And working people themselves were keen. This was largely because the mechanics’ institutes were very much local initiatives. Indeed, it may be problematic to write as though the rapid spread of mechanics’ institutes throughout the U.K. and world were part of a movement. It was more ad hoc than the term ‘movement’ implies. Mechanics’ institutes were established by local communities; they served local interests. The institutes in Australia and Ireland can be taken as examples. Colonists to Australia quickly adapted what they knew about mechanics’ institutes in Britain to the Australian context. Australian institutes were often based in under-developed, rural areas, such as Van Diemen’s Land (which, in 1827, established the first mechanics’ institute in Australia). These institutes were much more than simply educational establishments. Their buildings served as libraries, reading rooms, meeting spaces, galleries, and theatres, as well as venues for sports, fairs, weddings, baptisms, and funerals. Similarly, Irish communities had begun forming mechanics’ institutes from 1824. But, again, the context in which they were established was very different to the context in industrialized cities such as Manchester or London, for example. Like in Australia, Irish institutes were located in provincial, agricultural towns. They played an important role in cutting across sectarian divides, providing relatively neutral spaces where Catholics and Protestants could mingle.[29] Many Irish institutes were inspired by temperance politics, as was the Rotherham Mechanics’ Institute.[30]

Local needs varied. For example, the Ancoats Mechanics’ Institute in Manchester focussed very much on elementary reading and writing, in contrast to institutes in Newcastle, Nottingham, and Sheffield, which provided higher-level scientific instruction.[31] Membership also varied. Those in the north of England, for example, tended to attract more working-class members while the institute in Wakefield emerged out of a debating club led by local, middle-class savants.[32] This was commented on in the 1859 Annual report of the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes, which stated that it is a prevalent opinion that Mechanics’ Institutes are only so in name, their original purpose having been superseded by the rejection of them by the class for whom they were intended, and their adoption by the middle classes. But this is not true of the majority of those in Yorkshire, however it might apply elsewhere. Some of the most flourishing Institutes are composed almost wholly of the labouring class, and in most of them they form a considerable majority.[33]

Some were under the leadership of paternalistic middle-class leaders (this was the case of the Bradford Mechanics’ Institute)[34]; others, such as the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes, were dominated by the workers themselves.[35]

These differences were important because they reflected alterative visions of the purpose of mechanics’ institutes. Were they vehicles for improving social morality or a key to promoting an entrepreneurial ideal? Was the spread of the institutes due to enthusiasm by working people themselves to ‘better’ their position or was it more ‘political’ – that is, hotbed for the promotion of universal suffrage, factory reform, or even revolution? This diversity in aims has stimulated a lively debate about the value of the mechanics’ institutes. Even vigorous champions of education for working people had concerns. Famously, in The Condition of the Working Class in England (1844), Friedrich Engels (co-founder of Marxism) reproached the mechanics’ institutes for being ‘organs for the dissemination of the sciences useful to the bourgeoisie’. He accused their teachings of being ‘tame, flabby, subservient to the ruling politics and religion’. Taking this a step further, Engels even denounced the institutions for propagating a ‘constant sermon upon quiet obedience, passivity, and resignation to his fate’.[36] In contrast Engels believed that working people should be educated in proletarian reading-rooms, run by the workers themselves, rather than being sponsored by wealthy men such as Birkbeck and Brougham.

This critique has been taken up by some historians. In the words of historian of science Steven Shapin, the men establishing mechanic’ institutes not only believed that ‘a scientifically educated working class would aid the process of industrialization’ but they also regarded a ‘scientific education might prove to be an instrument of social control’.[37] This could involve subduing labour protests, encouraging workers to accept a particular version of economic management, or stifling sectarian conflict (as in Ireland).[38] The problem with the ‘social control’ argument is that it does not allow for high levels of inconsistency in the actual practices of the men and women within the various mechanics’ institutes and it over-states the greater degree of conscious manipulation of working people by the managers. Some institutes – most notoriously the London Mechanics’ Institution – expressively forbad any discussion of politics or religion.[39] However, this directive was not enforced in practice. In fact, the LMI rented out their rooms and lecture theatre to some of the most radical organizations of the time, including the Friends of Civil and Political Liberty, the Owenite London Co-operative Society, the Society for Promoting Radical Reform, numerous trade unions, socialists, and political radicals.[40] The mechanics’ institutes in Leeds and Manchester promoted Chartist and Owenite ideas; in Cheltenham, the writings of Bentham, Owen, and Cobbett were in the library; Sunderland welcomed Chartist leaders.[41] Furthermore, institutes that began with one motive – improving the ‘morals’ of working people – might develop into something much more emancipatory and socially diverse as the century continued.[42] Many of the institutes provided their members with vital organizational and administrative skills, which encouraged their members to participate in political movements and radical causes – indeed, it gave them the necessary skills to do so effectively. As economic historian John Laurent argues, working people used education to ‘transform agencies designed for social control into instruments for emancipation’.[43] They were a major propeller for the Labour movement, socialism, co-operation, social reform, and enfranchisement.

As argued throughout this essay, the definition of ‘useful knowledge’ was a fundamentally contested one. Deeply embedded ideas about class differences – including fundamental beliefs about the innate superiority and inferiority of the different social ‘orders’ – meant not only that working people were viewed as incapable of imbibing knowledge but that, when they did so, it could only result in societal chaos. The founders of the various mechanics’ institutes, as much as their opponents, had differing views about what was ‘useful’. Their members or students, also, sought education for a variety of motives, including social advancement, political ambition, and leisure. When addressing members of the Manchester Mechanics’ Institute, George Howard insisted that the Institute’s aim was to develop ‘the intellectual, the mental, and the higher qualities of our nature’. What that precisely meant was decided by working people themselves.

[1] John George Godard, George Birkbeck. The Pioneer of Popular Education. A Memoir and a Review (London: Bemrose and Sons, 1884), np.

[2] James William Hudson, The History of Adult Education, in Which it Comprised a Full and Complete History of the Mechanics’ and Literary Institutions, Athenæums, Philosophical, Mental and Christian Improvement Societies, Literary Unions, Schools of Design, Etc., of Great Britain, Ireland, America, Etc. Etc. (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1851), v.

[3] To the Members and Managers of the Mechanics’ Institutions in Britain and Ireland’, The Co-Operative Magazine and Monthly Herald, 1 (January 1826), 23-4.

[4] William Thompson, ‘To the Members and Managers of the Mechanics Institutions in Britain and Ireland’, The Co-Operative Magazine and Monthly Herald, 1 (January-February 1826), 12.

[5] Rowland Detrosier, quoted in ‘London Mechanics’ Institution’, The Examiner (25 September 1831), 619.

[6] Ibid.

[7] These sale figures were according to ‘A Reply to Mr Brougham’s ‘Practical Observations Upon the Education of the People, Addressed to the Working Classes and Their Employers’’, The Edinburgh Review, 42.83 (1 April 1825), 212.

[8] Review of Brougham’s tract entitled ‘’Practical Observations Upon the Education of the People; Addressed to the Working Classes and Their Employers’ (London, 1825)’, The Edinburgh Review, 41.82 (1 January 1825), 508.

[9] Henry Brougham, Practical Observations Upon the Education of the People. Addressed to the Working Classes and their Employers, 1st pub 1825 (Manchester: E. J. Morten, 1971), 31.

[10] Ibid., 4.

[11] Evidence from John Dunlop in the Report from the Select Committee on Inquiry into Drunkenness, with Minutes of Evidence and Appendix (5 August 1834), 412.

[12] Evidence by Rev. Dr. Nathan Marcus Adler, in Education Commission. Answers to the Curriculum of Questions, 1860. Vol. V, 19.

[13] Archibald Alison, First Report from the Select Committee on Combinations of Workmen; Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendix, 1838, 187.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Joseph Kay, The Social Condition and Education of the People in England and Europe; Shewing the Results of the Primary Schools, and of the Division of Landed Property, in Foreign Countries, vol. 2 (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, 1850), 506-7.

[17] Edward William Grinfield, A Reply to Mr. Brougham’s ‘Practical Observations Upon the Education of the People; Addressed to the Working Classes and Their Employers’ (London: C. & J. Rivinton, 1825), iv.

[18] Ibid., 10-11.

[19] Ibid., 17.

[20] Ibid., 25.

[21] Ibid., 30.

[22] Ibid., 30.

[23] Evidence from John Dunlop in the Report from the Select Committee on Inquiry into Drunkenness, with Minutes of Evidence and Appendix (5 August 1834), 412.

[24] Archibald Alison, First Report from the Select Committee on Combinations of Workmen; Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendix, 1838, 187.

[25] Evidence from Moses Angel of the Jews’ Free School, in Education Commission. Answers to the Curriculum of Questions, 1860. Vol. V, 48.

[26] Evidence by Rev. Dr. Nathan Marcus Adler, in Education Commission. Answers to the Curriculum of Questions, 1860. Vol. V, 19.

[27] ‘The Consequences of a Scientific Education’, Edinburgh Review (1 December 1826), 194.

[28] Rev. George Wright, Mischiefs Exposed. A Letter Addressed to Henry Brougham, Esq., M.P., Showing the Inutility, Absurdity and Impolicy of the Scheme Developed in his ‘Practical Observations’ (York: A. Barclay, 1926), 16.

[29] Elizabeth Neswald, ‘Science, Sociability, and the Improvement of Ireland: The Galway Mechanics’ Institute, 1826-51’, British Society for the History of Science, 39.4 (December 2006), 507.

[30] Ibid., 531.

[31] Martyn Walker, ‘’Encouragement of Sound Education Amongst the Industrial Classes’: Mechanics’ Institutes and Working-Class Membership 11838-1881’, Educational Studies, 39.2 (2013), 145.

[32] Ian Inkster, ‘The Social Context of an Educational Movement: A Revisionist Approach to the English Mechanics’ Institutes, 1820-1850’, Oxford Review of Education, 2.3 (1976), 281.

[33] Annual Report of the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes (Leeds: Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes, 1859), 2.

[34] Gerry Wright, ‘Discussions of the Characteristics of Mechanics’ Institutes in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century: The Bradford Example’, Journal of Educational Administration and History,33.1 (2001), 14.

[35] Martyn Walker, ‘’Encouragement of Sound Education Amongst the Industrial Classes’: Mechanics’ Institutes and Working-Class Membership 11838-1881’, Educational Studies, 39.2 (2013), 142-55.

[36] Friedrich Engels, Condition of the Working Class in England, 1st pub. 1844 (London: Panther, 1969), at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/condition-working-class/ch10.htm, viewed 1 August 2021.

[37] Stephen Shapin, ‘A Course in the Social History of Science’, Social Studies of Science, 10.2 (May 1980), 246. Also see Stephen Shapin and B. Barnes, ‘Science, Nature, and Control: Interpreting Mechanics’ Institutes’, Social Studies of Science, 7.1 (1977), 31-74.

[38] Elizabeth Neswald, ‘Science, Sociability, and the Improvement of Ireland: The Galway Mechanics’ Institute, 1826-51’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 39.4 (2006), 503-34.

[39] “The Members of the London Mechanics’ Institution”, Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (4 December 1825), 389.

[40] See my book, Birkbeck. 200 Years of Radical Learning for Working People (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

[41] Edward Royle, ‘Mechanics’ Institutes and the Working Classes, 1840-1860’, The Historical Journal, xiv.2 (1971), 317.

[42] Martyn Walker, ‘’Encouragement of Sound Education Amongst the Industrial Classes’: Mechanics’ Institutes and Working-Class Membership 11838-1881’, Educational Studies, 39.2 (2013), 142-55.

[43] John Laurent, ‘Science, Society and Politics in Late Nineteenth Century England: A Further Look at Mechanics’ Institutes’, Social Studies of Science, 14.4 (November 1984), 586.