This post was contributed by Dr Ben Winyard, digital publications officer at Birkbeck, University of London. Dr Winyard has been a co-organiser of Birkbeck’s Dickens Day event since 2005, and is one of the organisers behind the current Dickens reading project at the College

BBC drama Dickensian (image copyright Premier)

Is there a word for that familiar feeling of sadness or melancholia that accompanies finishing a novel? Perhaps there is a ferociously lengthy compound noun in German, or an elegant Japanese word with multiple, elusive meanings that can’t be fully encompassed by a solitary English word. A quick, unscientific search on Google reveals fascinating discussions on sites such as reddit about this emotional state and the various words that might describe it: sadness, ennui, nostalgia, regret, catharsis, homesickness, mourning, separation anxiety, and the delightful but somewhat toxic sounding ‘book hangover’.

Another suggestion is the term ‘limerance’, used in psychoanalytic theory to describe an invasive sexual and emotional obsession with a person or object – an infatuation or crush, in more demotic idiom. This feels a little too histrionic for such a quiet, fleeting but pervasive feeling. Imagining a curiously powerful parental bond, Dickens described David Copperfield as his ‘favourite child’, which suggests the intense feelings of attachment readers (and writers) can develop for fictional creations.

Do Dickens’s books deliver more noxious ‘book hangovers’? After all, Dickens was keen throughout his writing career to evoke feeling in his readers, meaning that his forceful use of sentimentality and melodrama, to induce laughter and tears in rapid succession (what Dickens described as his ‘streaky bacon’ approach), might be regarded as a particularly heady and intoxicating form of emotional pummelling. Dickens’s work provokes powerful feelings and his readers are famous for their attachment to the author and to his works. Dickens’s sentimental mode entices, coaxes and even coerces us to be affected by its depictions; it is a form of aesthetic and imaginative self-projection. Indeed, the shared, collective experience of feeling is what often brings us together as a community of Dickens enthusiasts.

It is also worth remembering that Dickens’s original readers would have encountered multiple hiatuses, as they read the novels serially in weekly or monthly instalments, which may have provoked feelings of frustration, anticipation, excitement and longing. A novel’s plot may be thrillingly propulsive, providing a forward momentum that, when halted, generates an exasperated thirst to traverse the ‘empty’ space in-between as quickly as possible. These manifold mini or false endings – which sometimes took the form of cliffhangers, but were more often simply breaks in the narrative – are similar to the final ending of the novel, in that they represent spaces that evoke fantasy and speculation. Just as the serialised instalments represent only temporary cessations that are potentially bridged by longing-filled fantasy, the end of a Dickens novel may similarly rouse imaginative speculation and fancy about the afterlives of the characters.

A scene from BBC drama Dickensian, featuring Stephen Rea in the role of Inspector Bucket (image copyright Premier)

Adaptation, reimagining, pastiche and outright bootlegging

Dickens was himself no stranger to this phenomenon. The exceptional success of his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, serialised in 1836–37, stimulated a veritable industry of adaptations, pastiches, rip-offs and continuations. One of the most famous was Pickwick Abroad; or, The Tour in France (1837–38) by George W. M. Reynolds, a hugely successful radical journalist Dickens intensely disliked. In this decidedly rough and ready sequel, the Pickwick Club ventures into France, where crass national stereotypes and risqué adventures abound. In an era before copyright law – for which he campaigned vociferously – Dickens witnessed the multiple imaginative afterlives of his stories and characters on stage and in unlicensed prequels and sequels.

There was also a bustling trade in Dickensian souvenirs featuring his characters, including illustrations, porcelain figures, china plates, Toby jugs, keepsake boxes, and miscellaneous other household items and collectibles. Interestingly, in his short-lived journal Master Humphrey’s Clock, which he wrote and edited alone between 1840 and 1841, Dickens acknowledged and indulged readers’ desire for afterlives and new adventures for their favourite characters by reintroducing the hugely popular Mr Pickwick and Samuel Weller. We can also sense in Dickens himself the irresistible urge to resurrect characters he evidently longed to spend time with again – just as many of his readers did.

A digital Dickens afterlife

More recently, Birkbeck’s inventive and successful Twitter retelling of Our Mutual Friend, which saw dozens of people tweet as characters in this multitudinous novel, provided an outlet for Dickens readers to reengage with, and extend the afterlives of, their favourite characters. Many tweeters were unafraid to present their characters in decidedly modern, updated terms, which meant that, while the novel’s plot remained essentially the same, many characters took on new aspects, had new adventures and relationships, and occupied more imaginative space than in the original work.

At the most recent Dickens Day (October 2015), Professor Holly Furneaux, an alumna of Birkbeck who is now based at the University of Cardiff, delivered a fascinating paper on Dickensian fan fiction online, which is forging communities and providing avenues for original, and even erotic, (re)engagements with popular Dickensian characters. Furneaux demonstrated the particular popularity of the triangular relationship between Mortimer Lightwood, Eugene Wrayburn and Lizzie Hexam in Our Mutual Friend, which many online Dickens fan fiction writers reimagined more capaciously, with space within Eugene and Lizzie’s marriage for Mortimer.

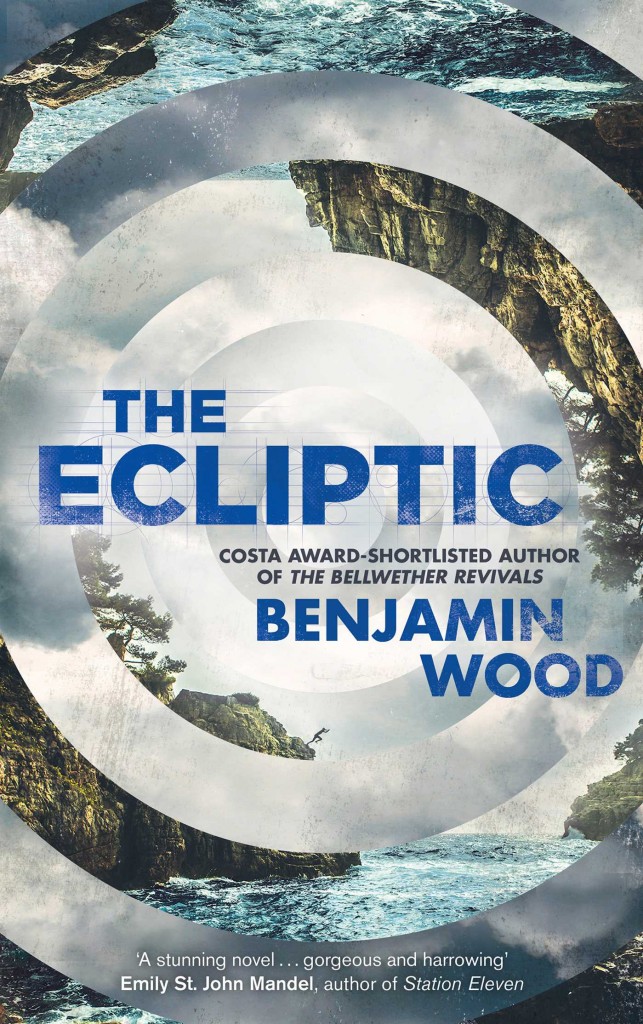

Dickensian – Goading the stuffy old gatekeepers

Given the powerful attachment of Dickens’s readers to his works and the long history of adaptation, reimagining, pastiche and outright bootlegging of Dickens’s work, Tony Jordan’s Dickensian feels less of an oddity or a provocation than it may first appear. In this twenty-part TV serial, we enter a fantasy Victorian world, in which many of Dickens’s characters, from several of the novels, coexist. Thus, Inspector Bucket (Bleak House, 1852–53) is investigating the demise of Jacob Marley (A Christmas Carol, 1843), with the forensic assistance of Mr Venus (Our Mutual Friend, 1864–65). Accompanying these fantastic mash-ups is Jordan’s reimagining of backstories and subplots in the novels; thus, Honoria Barbary is embarking upon a relationship with Captain James Hawdon that readers of Bleak House know is doomed. And in a delightful nod to the queer affiliations that Professor Furneaux has observed in online fan fiction and other literary and non-literary sources, Arthur Havisham is hopelessly in love with Meriwether Compeyson, the dastardly seducer he has appointed to marry and defraud his sister, Amelia (who will become the bitter, decrepit Miss Havisham of Great Expectations, 1860–61). The first episode of Dickensian thus presented a delightful, uncanny guessing game, as Dickens fan scrambled to identify all of the characters and connect them to their extant stories within the novels.

Jordan himself is keen to present his work as goading the stuffy old gatekeepers of Dickens’s legacy, irreverently insisting in an interview with the Daily Telegraph that ‘he knew the changes risked “p––ing off the Dickens community”’. In actuality, Jordan’s work taps into a rich seam of readerly fantasy about Dickens imaginative worlds that has been amply mined by authors, playwrights, filmmakers and TV executives. Furthermore, the intense relationship between Dickens and his readers, and the love and affection readers have felt, and continue to feel, for Dickens, his fictional world and the people who inhabit it, have all been objects of intense scholarly scrutiny and analysis.

Charles Dickens – By Jeremiah Gurney (Heritage Auction Gallery) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

It is a truism that all Dickens fans and scholars inevitably encounter that, ‘Were Dickens alive today, he would write for a soap opera’. Jordan, who famously wrote for Eastenders (and less famously, for the slated, 90s camp classic Eldorado), has been keen to emphasise that Dickens’s serialised fiction prefigured the episodic melodrama of the contemporary soap opera. In a recent interview with The Big Issue, Jordan observes that,

“People can be far too reverential. We mustn’t forget that Dickens was a populist writer who wrote for the masses. He wrote episodically, trying to flog magazines every month. He was sensationalist and did cliffhangers way before soap operas. He and Wilkie Collins said their secret was to make them cry, make them laugh and make them wait. That is everything I did in my EastEnders career. It is that deferment of gratification.”

The originality of Dickensian lies in its audacious bringing together of numerous characters at once, but one of the impulses that has powered this – the desire to make characters live again and to imagine them into new aspects, new stories and new worlds – accompanied Dickens’s fiction from its earliest moments. In the spaces in-between and after instalments, we find that readers’ emotional engagement births alternative and new stories, trajectories and lives that all demonstrate the enduring power of Dickens’s fiction.

Find out more