Dr Sarah Thomas, from the Department of History of Art, shares her experience of museum curation in Australia and discusses how we should interrogate the ‘hidden histories’ that underpin current debates.

In 1993 when working as a curatorial assistant in a public gallery in Sydney I was involved in a project which I’ll never forget. Yamangu Ngaanya. Our Land Our Body was an exhibition of paintings by a group of Aboriginal artists from a remote desert community in Warbuton, Western Australia. The dazzling canvases, derived from ancestral ‘Dreaming’ stories that were traditionally painted onto the body, were accompanied by forty-five Ngaanyatjarra men and women, most of whom had never visited a city in their lives and who had travelled to Sydney by coach over several days and nights. Besides the paintings they also brought with them sixteen tonnes of red sand from their land, which over the course of several days was dispersed over the gallery floor. What had been a standard ‘white cube’ interior was radically transformed into a space for ceremony: over several days and nights separate groups of women and men prepared and performed Dreaming ceremonies, filling the space with traditional song, language, dance, swirling dust, bodies painted in ochre, the smell of smoke and sweat. This was not what an art historical training had prepared me for: ‘performance art’, ‘installation’, and ‘body art’, even ‘painting’, were all wildly inadequate terms for what I observed over the course of that week.

I am reminded of this moment by the global repercussions recently of the Black Lives Matter anti-racism protests. The Australia I grew up in was deeply racist, and it remains so. Sadly, despite years of protest, public and scholarly debate, and a government apology in 2008 for the forced removal of Indigenous children from their families by national and state agencies, Indigenous Australians remain the most incarcerated people on earth. Leading Aboriginal artists have long been highly critical of Australia’s colonial past, and the pervasive hold it has on the present. Daniel Boyd, for example, critiques the nation’s foundational myths by reworking white Australian imagery, from heroic depictions of Captain Cook (statues of whom are currently the subject of heated debate) to encounters between Aboriginal and European settlers. I included Boyd’s painting We Call Them Pirates Out Here (2007) in an exhibition I curated in 2015 called Colonial Afterlives, which brought together the work of contemporary artists from former British colonies including Jamaica, Barbados, Guyana, Canada, New Zealand, as well as Australia.

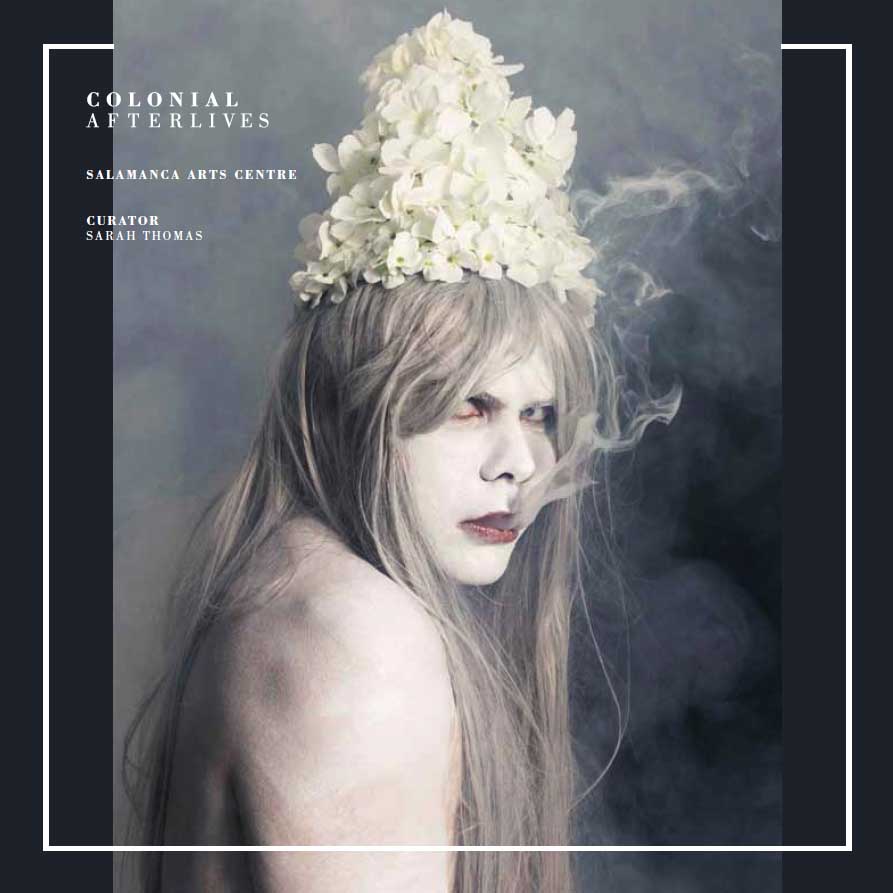

Colonial Afterlives exhibition catalogue cover. Image by Christian Thompson, Trinity III, from the Polari series, 2014. Christian Thompson is represented by Sarah Scout Presents (Melbourne) and Michael Reid Gallery (Sydney and Berlin).

Over the past decade, I’ve been researching the European representation of enslaved people in the 18th and 19th centuries across the Caribbean, Brazil and antebellum America (the subject of my book, Witnessing Slavery: Art and Travel in an Age of Abolition). More recently, I’ve been talking to museum professionals and scholars across the UK about how their institutions might publicly acknowledge the cultural legacies of slavery. The work of UCL’s Legacies of British Slave-ownership project has uncovered a wealth of data about slave-owners at the moment of British emancipation in 1833, when a grant of £20 million (40% of Britain’s national budget) was paid in compensation, by British taxpayers to slave owners. My research draws on this work, focussing on the impact of slave-owners as art connoisseurs, collectors and patrons on the early history of British art museums.

There’s no doubt that such ‘hidden histories’ are troubling. The toppling of the statue of slave-trader Edward Colston on 7 June was not simply a spontaneous action born out of collective rage, but one with a long and more complex history of thwarted community attempts to acknowledge publicly Colston’s role in the slave trade. Madge Dresser points out that when the statue was erected in 1895 (over 170 years after the subject’s death), it coincided with the building of monuments which glorified the Confederacy in the United States, and others in Britain and across its Empire, which: ‘similarly extolled the virtues of British imperial figures whose relationship with colonised people of colour ranged from the paternalistic to the genocidal’. Historian Nick Draper is right when he says: ‘Historians need to be realistic about their reach and influence. But for more than 30 years scholars have worked towards an adequate post-colonial account of Britain’s history as a colonising and imperial power.’ He cautions: ‘We have tried to establish an evidence base that can be drawn on by all parties. The hegemonic view of British exceptionalism, its unique commitment to liberty and its glorious imperial past, has been challenged, but it has survived. Had we collectively succeeded, then some of the paths not taken would have been pursued. The binary of leave it alone/tear it down might have been avoided’. There is a sense of disappointment in this statement, as if historians themselves have in some sense failed in their attempts to challenge the status quo. But it is this ‘evidence base’ that is so vital to what we do as art historians as well, and why in our teaching we often speak about ‘authoritative sources’ and the importance of primary archival research.

Australia has a longer history of grappling with its colonial (British) past. As a curator in a big state art museum in the late 1990s, I was part of a generation that began to question the traditional separation in collection displays of ‘Aboriginal art’ and ‘Australian art’, interrupting Euro-centric chronological displays by introducing works of contemporary Indigenous artists, such as Boyd. (European visitors had no doubts about what constituted ‘Australian art’: they headed straight for the Aboriginal art collections.) My first sustained encounter with Aboriginal art and its makers in 1993 was profound, and its complexities and contradictions have stayed with me over the course of my career and feed now into my teaching. In Britain, museums are starting to engage more directly with the deeper implications of empire (see, for example, The Past is Now: Birmingham at the British Empire, 2017), but there is still much work to be done.

Art historians today are attentive to the complexities of social context, and careful to avoid the simplistic dualisms that newspapers, politicians and much social media commentary thrives on. Public statues have garnered attention across the world as lightning rods for heated and often bitter debates about national identities, yet the very fabric of our cities and countryside – street names, public buildings, museum collections, archives, country houses, to name just a few examples – is steeped in the residue of history. This reminds us that colonial business is unfinished, its legacies are raw; history is now, and it matters.

Sarah Thomas is Lecturer in Museum Studies and History of Art in the Department of History of Art, and Director of the Centre for Museum Cultures. In Autumn term 2020, she will be teaching the seminar ‘Slavery and Its Cultural Legacies’ as part of the MA Museum Cultures and MA History of Art.