Dr Frederick Cowell, Lecturer in Law, argues that the UK’s exiting the EU may have saved the Human Rights Act and secured Britain’s long term future as party to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The Brexit process has, in short, pushed the UK government away from what was, until recently, a clearly stated policy – to repeal the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), replace it with a British Bill of Rights and eventually withdraw from the ECHR. Both a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and HRA repeal, were in the Conservative Manifesto for the 2015 General Election. Repeal of the HRA, which brings the ECHR into UK law and requires UK judges to take the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights into account, has been a stated aim of the Conservative Party since 2006. In fact, its position on the HRA was clearer in its 2010 manifesto than its commitment to EU withdrawal. Coalition with the Liberal Democrats and the creation of the Commission on a British Bill of Rights appeared to kill the idea but, in 2014, the Conservative Party Published its proposals for a British Bill of Rights to replace the HRA.

The Brexit process has, in short, pushed the UK government away from what was, until recently, a clearly stated policy – to repeal the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), replace it with a British Bill of Rights and eventually withdraw from the ECHR. Both a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and HRA repeal, were in the Conservative Manifesto for the 2015 General Election. Repeal of the HRA, which brings the ECHR into UK law and requires UK judges to take the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights into account, has been a stated aim of the Conservative Party since 2006. In fact, its position on the HRA was clearer in its 2010 manifesto than its commitment to EU withdrawal. Coalition with the Liberal Democrats and the creation of the Commission on a British Bill of Rights appeared to kill the idea but, in 2014, the Conservative Party Published its proposals for a British Bill of Rights to replace the HRA.

Entitled Protecting Human Rights in the UK, it proposed breaking the link between UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights, and withdrawing from the ECHR if that was not possible. If implemented, this would have left the UK the only nation in continental Europe (apart from Belarus) that was outside the ECHR. It would likely have been incompatible with the Treaty on the European Union, which commits EU member states to respecting human rights, as defined by the ECHR, as a core EU value. However, as the 2014 policy document went onto note, ‘our relationship with the EU will be renegotiated in the next parliament’ and if there were any problems with the UK’s new bespoke human rights agreement this would be addressed ‘as part of the renegotiation.’ Linking leaving the EU with ECHR withdrawal made sense in terms of political framing. Although being outside the EU has no bearing on ECHR membership – Norway and Switzerland are not EU member states but have been party to the ECHR for almost half a century – the European Court of Human Rights was considered another ‘foreign court’ in the newspapers and political circles that would go onto become the most enthusiastic Brexit supporters.

There is no evidence that renegotiating EU values so as to allow the UK to withdraw from the ECHR but remain in the EU was ever seriously discussed during David Cameron’s attempted renegotiation of EU membership in late 2015. Given that both the EU Justice Commissioner and the President of the European Commission had indicated a few years earlier that any member state attempting to withdraw from the ECHR would raise concerns ‘as regards the effective protection of fundamental rights’, it is highly unlikely that Cameron would have been successful even if he had tried. After winning the 2015 General Election the entire project appeared to slow down; the then Justice Secretary Michael Gove promised proposals on a British Bill of Rights to repeal the HRA within months but, by the end of 2015, nothing had been published. By then academics and legal commentators had started to highlight the constitutional difficulties of HRA repeal, especially in relation to devolution, but the government continued to signal they were fully committed to HRA repeal.

In June 2016, when Theresa May became Prime Minister, she was expected to continue with the policy – she was a long-time opponent of the HRA from her days as Home Secretary, when she infamously and incorrectly claimed that HRA had blocked her from deporting someone because of their pet cat. But, in December 2016, the Attorney-General Jeremy Wright announced that HRA repeal was delayed until after the conclusion of Brexit. In the 2017 Conservative General Election Manifesto HRA repeal and ECHR withdrawal was effectively cancelled for the duration of the next parliament. This was far from popular among the Conservative Brexit supporters but the numbers in the 2015-2017 parliament made repeal difficult (a problem which worsened after the 2017 election). Also, with all of the constitutional difficulties over Brexit, there was little appetite to create an additional set of constitutional problems.

Since the autumn of 2017, the European Parliament has been clear that an important component of a future EU-UK relationship would be the UK’s continued ECHR membership. In the summer of 2018, the European commission draft report on future security cooperation again made membership of the ECHR an essential condition. Theorists of international relations and international law have argued that one of the core reasons for states joining the ECHR was to create a form of democratic lock-in, where the rights contained in it and the frameworks designed to protect them would be locked in place, in part because it would be hard for states to leave the Convention. Although it is superficially easy for a country to leave the ECHR, an exit mechanism is contained in Article 58 of the Convention and there are no direct economic consequences to a state for doing so, the ECHR’s interconnection with other European institutions creates a layer of political restraints constraining exit. The prospect of an exit agreement was clearly used as a lever by the European Parliament in their March 2018 resolution, which required any future trade agreement to be in “strict accordance” with EU values, effectively keeping the UK in the ECHR.

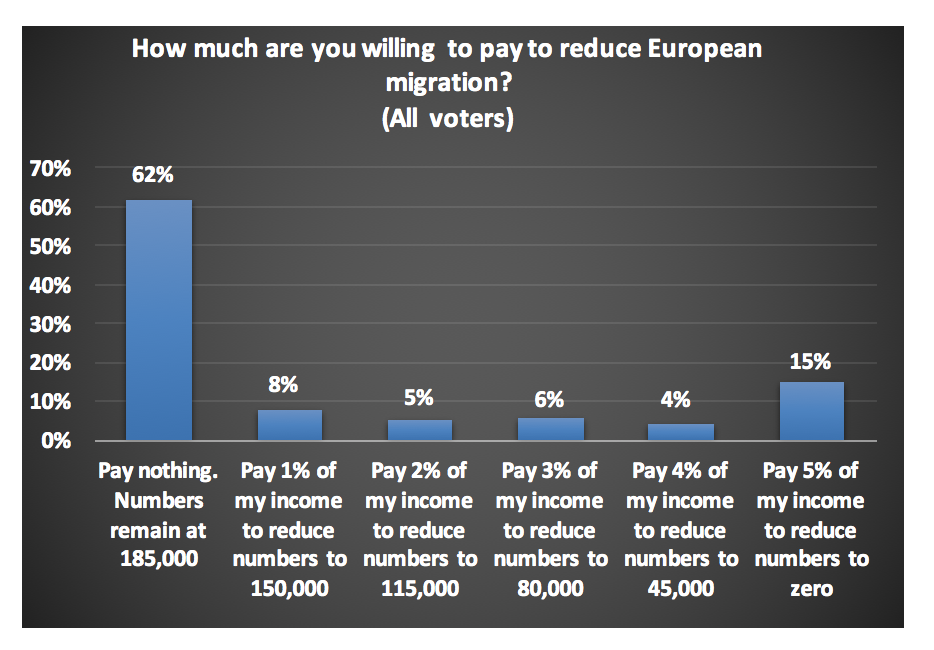

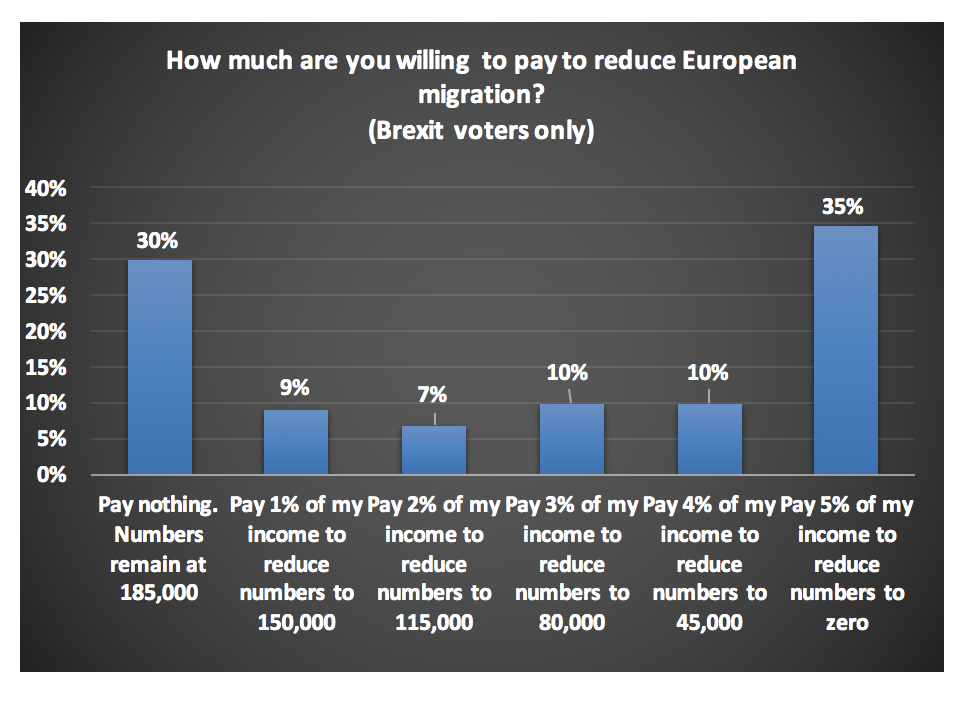

This could be important for securing the HRA’s future because there remains a significant political appetite for its repeal. Human Rights campaigners in the UK are often reassured by polling showing that HRA repeal is not a high public priority. But polling taken over a number of years in response to controversial or high profile decisions from the European Court of Human Rights has identified a significant degree of sympathy for the arguments advanced by the ECHR’s critics. Many of the arguments ranged against both the EU and the ECHR deploy what Fiona de Londras calls the ‘new sovereigntism’ argument – the idea that states should only engage and comply with international courts as and when they want to. Dominic Cummings, the leading political strategist for the Vote Leave campaign, announced earlier this year that he wants a referendum on the ECHR, noting that many leave voters would be ‘mad’ when they realise the UK was still party to it. Given this context, the external economic and political forces locking the UK into being a party to the ECHR as part of the Brexit process have probably secured the HRA’s future – for now.

This piece was first published on LSE’s blog.