This post was contributed by Professor Eric Kaufmann from Birkbeck’s Department of Politics. It was originally published on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

Lowering immigration was the key motivation behind the Brexit vote, and how to achieve it dominates the current political debate. Drawing on new data, Eric Kaufmann analyses the propsects of support for a hard and a soft Brexit, based on how much Britons would be willing to pay to reduce the number of Europeans entering the UK.

A new survey shows most Britons are not willing to pursue hard Brexit if it will cost them personally. Thus far, the economic indicators post-Brexit don’t look bad. Consumer spending and investment are holding up well, despite a lower pound. But if the going gets tough, there is a two-thirds majority willing to accept current levels of EU migration to retain access to the single market.

The leading motivation for Leave voters was reducing immigration while Remain voters prioritised the economy. This hasn’t changed. According to my YouGov/Birkbeck/Policy Exchange survey data, two-thirds of British people want less immigration, including 47 percent of Remainers and over 91 percent of Leavers.

Hard Brexit is a good way to bring numbers down. However, some suggest that when Theresa May triggers Article 50, the EU will drive a hard bargain, inflicting pain on the British economy. With economistsclaiming entry to the single market is worth 4 percent of GDP by 2030, I asked how much the average Briton is willing to sacrifice to reduce European immigration in the event the doomsayers are right. The final deal between Britain and the EU over leaving will hinge on how much economic pain, in the form of reduced market access, Britain is prepared to absorb to restrict European immigration.

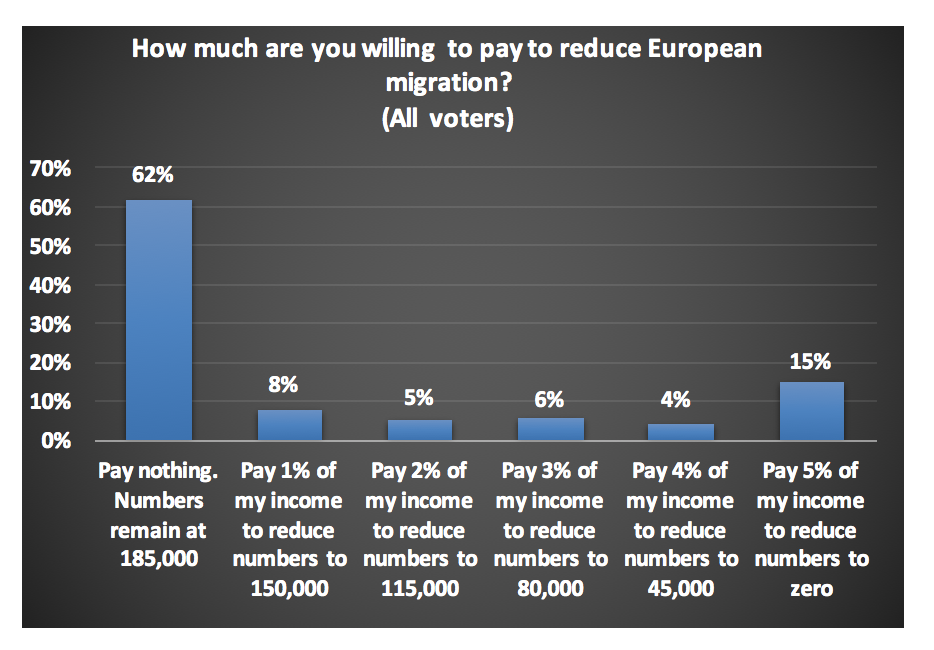

The survey, carried out by the polling firm YouGov, asked a sample of over 1500 people the following question: “Roughly 185,000 more people entered Britain last year from the EU than went the other way. Imagine there was a cost to reduce the inflow. How much would you be willing to pay to reduce the number of Europeans entering Britain?” The options ranged from “pay nothing” for no reduction to paying 5 percent of personal income to reduce numbers to zero. Each percent of income foregone reduced the influx by 35,000. The results are shown in figure 1.

Among those surveyed, and excluding those who didn’t know, 62 percent said they were unwilling to pay anything to reduce numbers, and would accept current levels of European immigration.

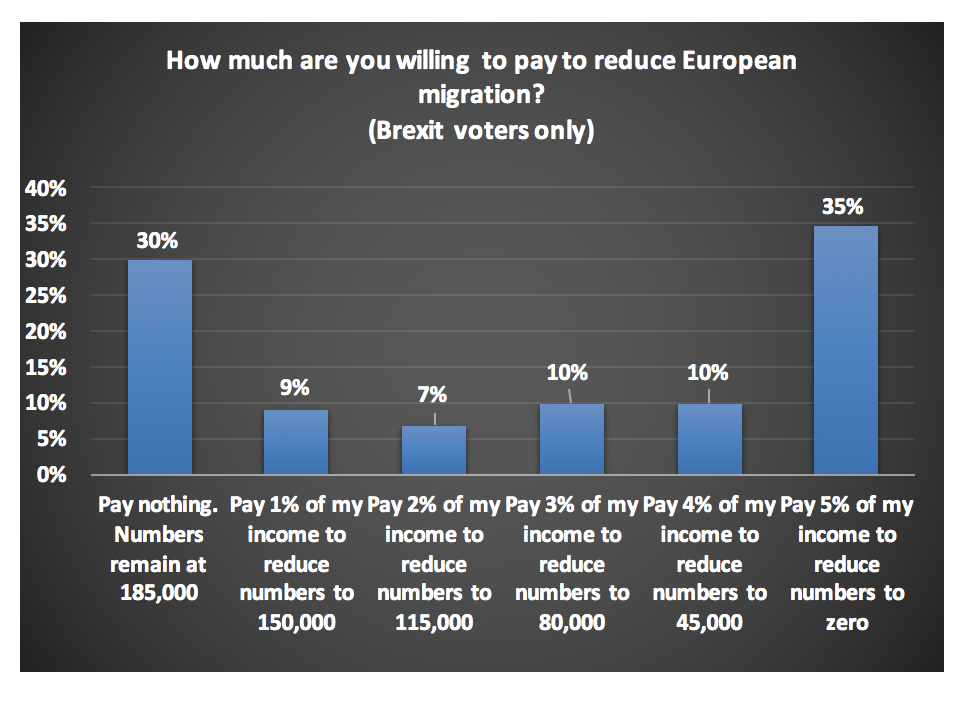

As figure 2 shows, even among those who said they voted to leave the European Union, 30 percentreported they would prefer the current inflow of 185,000 to paying any of their income to cut the inflow. In other words, there is a significant ‘soft’ component within the Leave vote.

On the other hand, there is a considerable core of Brexit voters willing to tighten their belts to reduce migration: over a third of Leave voters indicated they would contribute 5 percent of their income to cut European migration to zero. More than half of Brexiteers are willing to pay at least 3 percent of their income to reduce European net migration from the current 185,000 to under 80,000. The average person who voted Conservative in the 2015 General Election is willing to stump up 2.5 percent of their pay packet to reduce European immigration to half its current level.

This means that if the costs of Brexit mount in line with pessimistic predictions, most British people favour a deal that preserves market access even if this results in only limited reductions in European immigration. May’s Conservative voters will put up with more pain, but not if it costs more than 2 percent of GDP. This suggests a deal between Theresa May and her EU interlocutors based on significant market access in exchange for limited migration controls may be acceptable to the 45 per cent of voters who currently back her party. It certainly will pass muster with a majority of the electorate.

If the economy continues to hold steady, the question is moot and hard Brexit remains a strong option. But if pain is on the way after Article 50, Middle Britain will be inclined to prefer soft over hard Brexit.