This post was contributed by Dr Lorraine Lim, Lecturer in Arts Management in Birkbeck’s Department of Film, Media and Cultural Studies.

The past 10-15 years have seen interest in arts and cultural products from East Asia in Europe steadily increasing. Regular screenings of Japanese Anime films such as Spirited Away by Studio Ghibli are no longer confined to the art-house circuit and it would probably be difficult to find someone who has not heard or seen the Korean pop song Gangnam Style by Psy. Artists such as Yayoi Kusuma have had a retrospective exhibition at the Tate Modern recently and both modern and historical Chinese art have been showcased at the Barbican Centre and the British Museum.

The past 10-15 years have seen interest in arts and cultural products from East Asia in Europe steadily increasing. Regular screenings of Japanese Anime films such as Spirited Away by Studio Ghibli are no longer confined to the art-house circuit and it would probably be difficult to find someone who has not heard or seen the Korean pop song Gangnam Style by Psy. Artists such as Yayoi Kusuma have had a retrospective exhibition at the Tate Modern recently and both modern and historical Chinese art have been showcased at the Barbican Centre and the British Museum.

There is no doubt that the growth in technology has allowed many more people to access myriad arts and cultural products from East Asia. After all, the music video for Gangnam Style became the first video to reach a billion views on YouTube. With Japanese anime, bilingual fans on internet communities provide translation services for free to allow non-native Japanese speakers to watch or read the latest manga and anime. However, can the growth in visibility and interest of arts and culture from East Asia be linked to technology alone?

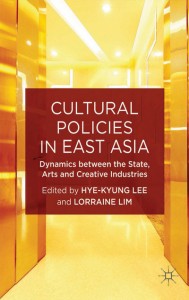

My book Cultural Policies in East Asia: Dynamics between the State, Arts and Creative Industries (written with Dr Hye-Kyung Lee) attempts to shed some light on how arts and culture in East Asia have developed in the recent past through looking at various government cultural policies to determine what has led to the various arts and cultural products that most of us in Europe are familiar with today.

The countries covered in the book: China, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan while occupying a geographical diverse space, share many common historical and cultural features which allow for interesting comparisons. A common history of colonisation, for example, has resulted in cultural policies where governments in Singapore and Taiwan have used arts and culture to create or nurture common national identities. Culturally, it has been argued that these countries possess strong Confucianist traits such as a respect for authority and a belief in success through hard work. These cultural traits have led to the support of arts and culture that is built on strong state intervention. Countries such as China and South Korea are two such examples where artists are in constant negotiation with the government. While many of the countries in the book examine the problems that can occur when the state intervenes too closely with arts and culture, Japan provides an interesting counterpoint where decades of a ‘hands-off’ approach is now being questioned by the arts and cultural community.

A historical look at the development of arts and culture in these countries provide a snapshot of the current state of arts and cultural development in the region. At the moment, the continued economic growth of these countries in East Asia (and Asia in general) have led to a corresponding increase in their political power and a desire to make a mark on the global cultural landscape. The governments in these countries are investing more money into supporting arts and culture as they recognise the potential impact arts and culture can have in the world. By examining the support for the creative industries through online games, the film industry and the development of creative clusters, the book offers a look at where the future lies for arts and culture in East Asia.

One thing is for sure; in the near future it will be highly likely that the next big pop song or movie will come from East Asia!