Dr Nancy Doyle (Founder and CRO of Genius Within CIC) and Professor Almuth McDowall ask where we can look for good research on neurodiversity at work and what are the most important knowledge gaps to fill. This lay summary of the research was composed by Nicola Maguire-Alcock.

We live in a time where there is an increased understanding that humans are all different, not only by our physical characteristics, but also how we think and behave. The term ‘neurodiversity’ was first termed by Judy Singer in 1999 to explain why humans naturally have a range of differences in our brains and why we behave differently.

Having an unusual neurotype can mean that there are large gaps between a person’s strengths and those things that they may struggle with, compared with a neurotypical person where the gaps are much smaller. There are a number of examples of neurodifferent conditions such as Autism, Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder, Tourette Syndrome, Dyspraxia and Dyslexia.

More recently, the term ‘neurominority’ has been used instead of neurodiverse in order to provide an understanding that those with an unusual neurotype are at a disadvantage in a range of daily life outcomes, in particular socially, in education and in employment.

Fortunately, understanding regarding neurodiversity has increased in these areas, however it is still a long way off where it needs to be. For example, in the workplace, even with initiatives and policies to support neurominorities, there is a lack of research that looks at the effectiveness of this support and there is not an approach that brings inclusivity from designing a job role through the life cycle of an employee.

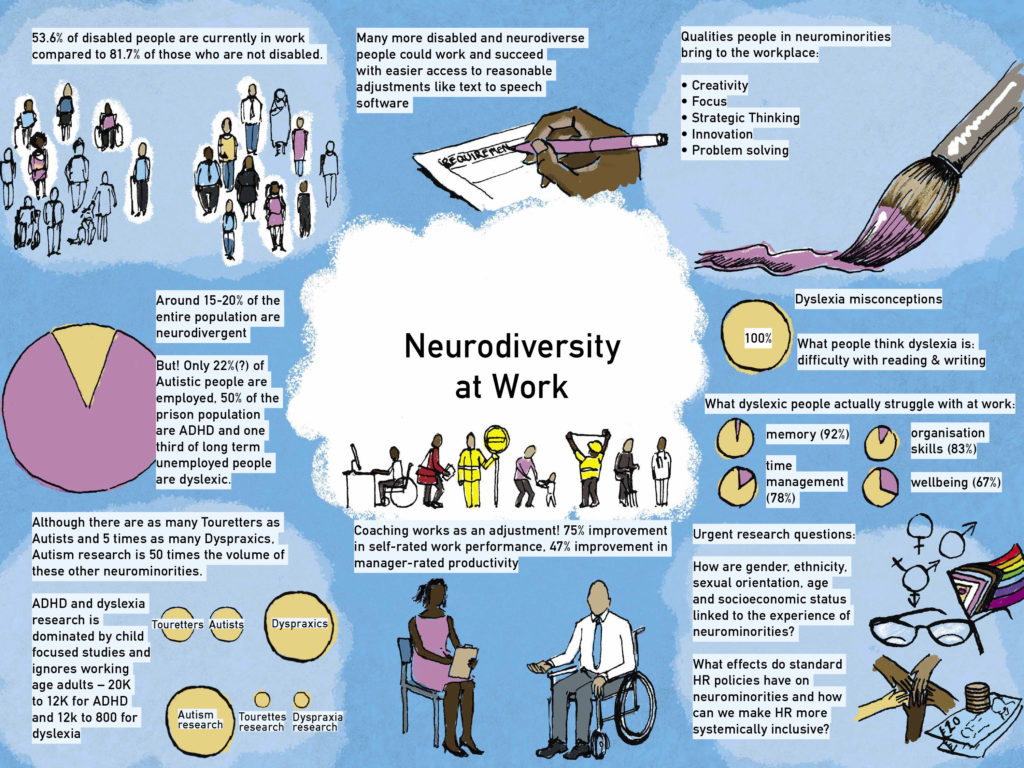

Furthermore, as well as limited research in this area, there is also an unfairness in the research that currently exists on neurominorities and into the understanding into ‘what works’ to improve making working environments inclusive.

Firstly, there is an imbalance of research into this area, due to there being a large focus on Autism and mental health at the disadvantage to other neurominorities. ADHD, Dyslexia, DCD, and Tourette Syndrome are all under-researched considering how common these conditions are in society. This means that there is a large risk of ignoring other neurominorities in the work place and a lack of focus on what is needed to improve everyday lives in the working world.

Secondly, we do not have informed practice from those who are living and experiencing these issues. This would bring a huge benefit in understanding and improving the current initiatives that are already in place in this area.

Have a look at the following questions:

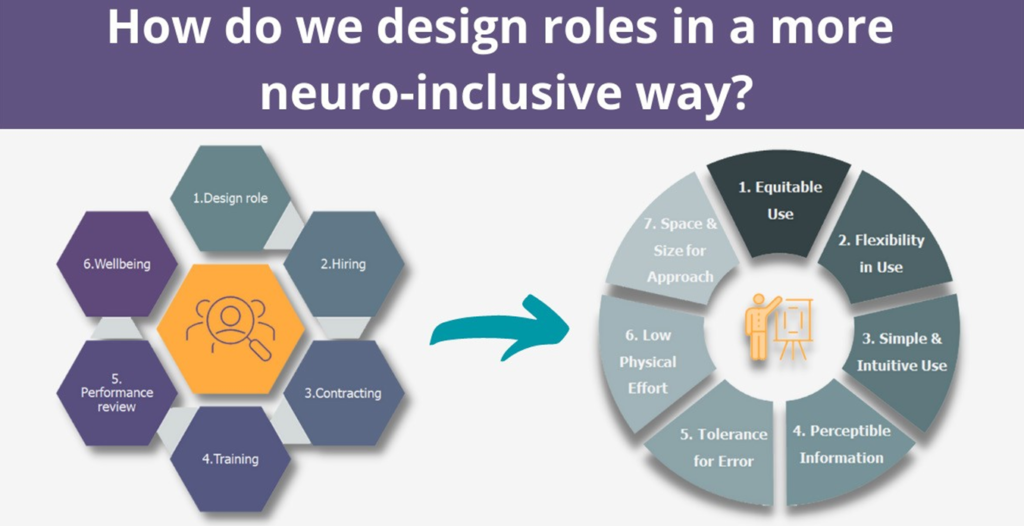

- How do we design roles in a more neuro-inclusive way?

- How do we hire to ensure all candidates can perform at their best during the process?

- How do we contract ensuring that the terms and conditions of employment are inclusive?

- How do we provide training which is inclusive?

- How can we provide performance reviews which increase success, with inclusive delivery?

- How can we change standard wellbeing services to support neurominorities’ needs?

Great opportunities as a business and for the individual can be gained as we take forward a new way of working which provides a simple, flexible, friendly model for Human Resources (HR).

Great opportunities as a business and for the individual can be gained as we take forward a new way of working which provides a simple, flexible, friendly model for Human Resources (HR).

In order to address this, it has been proposed that the Principles of Universal Design are applied through the employee life cycle. This provides a process for HR to follow in the workplace.

By using this, it provides the opportunity to create a workplace that works for everyone, which will really change the ‘can nots’ to the ‘can!’. Let’s not wait to miss opportunities that would limit your workforce, limit your company and increase the prevalence of staff becoming stressed or leaving. Now is the time to update your practice and apply this model.

Universal Design provides a set of principles that can guide HR to work at its best, at any point of the employment life cycle. There really is no better time but now to take action.

Please take a look at this illustration:

Further Information: