Catherine Heard, director of the World Prison Research Programme, at the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research at Birkbeck discusses pre-trial imprisonment.

Justice for Kalief Browder rally, New York, 2015. Credit: Felton Davis

Today, around 3 million people are in pre-trial (or ‘remand’) detention, awaiting trial or final sentence: roughly a third of the world’s prisoners. Some will see their cases dropped before trial. Some will be acquitted and released. Others, although convicted, won’t receive a custodial sentence. Whatever the outcome, the experience could have life-changing consequences, such as loss of employment, family and community ties; homelessness; and deterioration in physical or mental health.

Many pre-trial prisoners are held for months or years, their cases languishing in congested court lists. Kalief Browder spent three years in Rikers Island jail in New York, but was never tried or sentenced. Aged 17 when his detention began, he endured appalling abuse and spent hundreds of days in solitary confinement. Accused of stealing a backpack, he insisted on his innocence, resisting pressure to plead guilty in exchange for his release. At the many court hearings during his detention, the judge rubber-stamped repeated prosecution requests for more time. Eventually, the case was dropped due to lack of evidence. Kalief was released but tragically, two years later, he committed suicide.

Kalief’s case shows the casual disregard that criminal justice systems so often have for the lives, rights and freedoms of those caught up in their machinery. It’s not just an American problem. All over the world, people unable to pay bail or afford a good lawyer are being consigned to months or years in pre-trial detention, while those with money or social status find it easier to avoid prison.

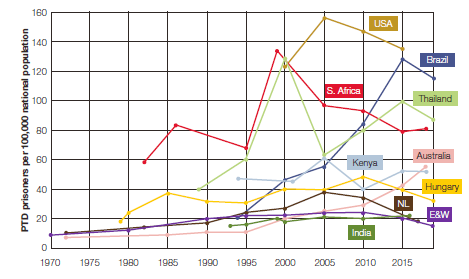

Why it matters: The misuse of pre-trial imprisonment is a major, but preventable cause of prison overcrowding; and a severe infringement of fundamental rights. It causes economic and social harm, puts pressure on prison conditions and increases the risk of crime. Pre-trial detention statistics held on ICPR’s World Prison Brief database show that, since 2000, pre-trial prison populations have grown substantially across much of the world. This is despite increased availability of cheaper, less restrictive measures like electronic monitoring.

Research in ten countries: Our new report, Pre-trial detention: evidence of its use and over-use in ten countries, looks at pre-trial detention in ten jurisdictions: Kenya, South Africa, Brazil, the USA, India, Thailand, England & Wales, Hungary, the Netherlands and Australia. All but one of these (the Netherlands) currently run their prison systems over-capacity. The rate of pre-trial detainees per 100,000 of the national population varies significantly among these countries. Several of them have seen very substantial rises in their pre-trial imprisonment rates, as shown in the figure below.

Change in pre-trial detention rate (number of people held pre-trial per 100,000 of the population) since 1970*

*Figures are from earliest date for which reliable data are available to most recent data as of September 2019.

Causes of pre-trial injustice: Our research included analysis of national legal systems followed by interviews with 60 experienced criminal defence lawyers across the ten countries. We found a gulf between law and practice: although legal systems (in line with international standards) refer to pre-trial detention as an exceptional measure it is, in practice, more often the norm. The problem is rarely the law itself, but wider socio-economic and systemic factors that influence its (mis)application.

People from backgrounds of disadvantage are more likely to be arrested, often don’t have money to pay bail, are less likely to have good legal representation – and for these reasons are more likely to be detained pre-trial. Aspects of the wider criminal justice ‘machinery’ are also part of the picture: under-resourced police and prosecution services that can’t investigate quickly and effectively; inadequate legal aid; lack of judges and court staff; unmodernised court infrastructure and technology; too few alternatives to custody. All these factors lead to misuse and prolongation of pre-trial imprisonment.

Judicial culture and practice were also identified as problematic, with judges described as being too ready to make unsupported assumptions about risk; too quick to dismiss defence arguments about weak evidence or ways to mitigate risk; overly influenced by fear of media (and social media) criticism; and disinclined to give concrete, evidence-based reasons for their decisions to remand in custody.

Our recommendations for tackling misuse of pre-trial detention are concrete and grounded on the research findings. We’ll be presenting them to policy-makers, practitioners and civil society bodies over the coming months.

More information

Read the full report by ICPR’s Catherine Heard and Helen Fair: https://prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/pre-trial_detention_final.pdf

Read the brief: https://prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/pre-trial_detention_briefing_final.pdf

See the latest data on prison populations worldwide, at ICPR’s World Prison Brief database: https://prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief-data

About ICPR’s World Prison Research Programme: https://www.icpr.org.uk/theme/prisons-and-use-imprisonment

Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research, School of Law, Birkbeck: https://www.icpr.org.uk/