This lay summary is based on the chapter ‘Neurodiversity in Higher Education: Support For Neurodifferent Individuals and Professionals’ by Dr Nancy Doyle in ‘Neurodiversity: From Phenomenology to Neurobiology and Enhancing Technologies‘ edited by Lawrence K. Fung. The summary is written by Nicola Maguire, Psychologist at Genius Within CIC.

As time evolves, the understanding that humans are different is becoming more widely understood and accepted. However, when it comes to higher education (HE) we still live in a world where there is one system, one path to success despite knowing that individuals can be completely different learners, thinkers and doers.

For many neurodifferent students, accessing higher education still feels impossible. So, the issue that is presented in the chapter is that the higher education setting as it currently stands does not help everyone to flourish, to foster self-belief and build confidence. Rather people experience feelings of failure, not having self-belief and a lack of confidence.

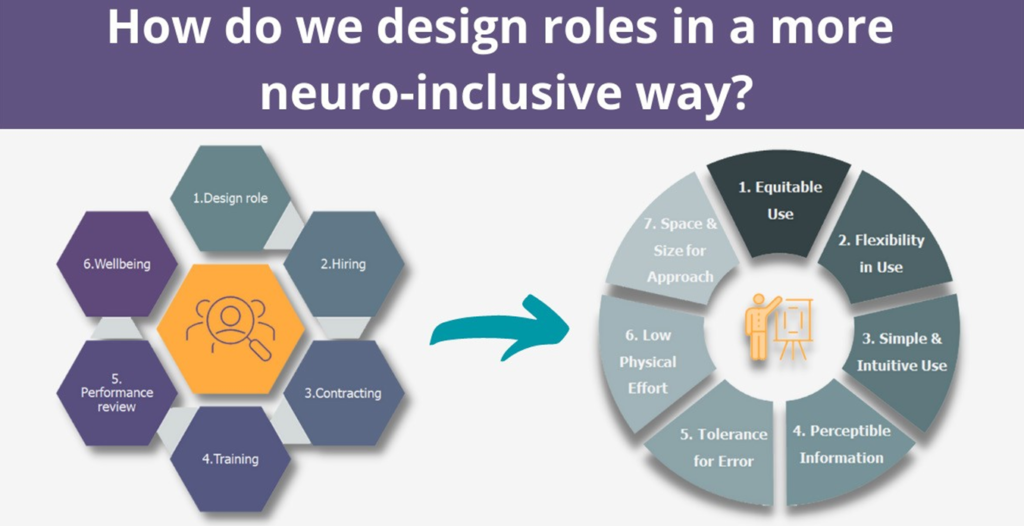

In order to address this, the chapter notes that systems in higher education can be

redesigned to support neurodifferent students. The chapter suggests creating a ‘Universal Design’, based on disability research, to ensure that all students have equal access to learning. Universal Design creates a learning journey that considers the needs and abilities of all learners and removes unnecessary hurdles in the learning process.

In order for this to work, universal design principles need to be applied across contexts in the HE system.

Systems can be changed in the following areas:

- Environment for learning

- Learning materials provided

- Testing conditions

The main ways to flex these areas is in considering the senses. Avoiding overwhelming, loud environments and giving students choice and flexibility about where they learn.

Making sure learning materials can be listened to or read, at different speeds and in multi-sensory formats. Give opportunities for questions asked live but also via chat. Testing conditions to reduce time pressures and reduce sensory overwhelm.

Additional supports can also be offered to individuals:

- Assistive technology

- Coaching

- Mentoring

- Group coaching

The most important thing for student support is building independence rather than doing things for students. They need to transition to the workplace when they leave HE. Therefore, they need to be doing things for themselves more and more. Coaching should be aimed at reinforcing strengths and self-awareness of barriers.

Conclusion

Higher education should and needs to be offering ND students different types of support. A Universal Design in environment, learning and tests would enable higher education to become accessible and achievable.

Alongside the combination of supportive measures such as coaching, mentoring and group coaching to increase self-efficacy in ND students. By implementing this approach in a higher education setting it will safeguard that ND students have equal opportunities to do their best, by ensuring that the process is proactive, positive and that appropriate support is provided for all.

We can deliver a much-needed healing and self-affirming experience to students through this process which will result in individuals building their self-belief in their ability to ‘be able to’ which means the difference between career aspirations being met or falling short.

‘Neurodiversity is a moral, social and economic imperative; we all lose when

human potential is squandered’