As part of Birkbeck’s Discover our research activity, Dr Suzannah Biernoff, senior Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Visual Culture in the Department of History of Art writes about her current research activity.

Dr Suzannah Biernoff

Hi Suzannah. What was your route to Birkbeck?

I moved to London from Sydney in 1998, after finishing my PhD. Before taking up a lectureship at Birkbeck in 2007 I taught on the Visual Culture programme at Middlesex University and at Chelsea College of Art and Design.

What’s your current topic of research?

My most recent publications have examined attitudes towards disability and disfigurement during and after the First World War. My book, Portraits of Violence: War and the Aesthetics of Disfigurement, is due out with the University of Michigan Press early next year. Wellcome funding has made it possible to publish open access articles in journals including Social History of Medicine, Visual Culture in Britain and Photographies.

I wanted to use visual sources as much as possible – from medical photographs and life drawings to prosthetic masks, photo albums and images in the illustrated press – sources that complicate and at times contradict the written record. As a historian of visual culture I am also interested in how people viewed the disfigured face. Cultural prohibitions against staring, expressions of pity or disgust, and later in the century the visual thrill of the horror movie: all of these ‘ways of seeing’ are part of the story, as much as the material evidence of injury, masking and repair.

I have recently been awarded a Birkbeck Wellcome Trust ISSF mid-career fellowship to begin a new project on images of facial difference within European and North American popular culture, film and visual art in the 20th and 21st centuries. I am interested in how people have responded to unusual or extraordinary faces; the cultural mechanisms of normalisation; and strategies of defiance and re-interpretation (for example, where the damaged face is re-imagined as beautiful, or where artists use disfigurement as a creative or symbolic device). As well as artistic representations of the face, my sources include public health images, advertisements, medical photographs, coffee table books, film and fashion photography.

Why did you choose this topic? What inspired you?

In autumn 2002 I went to the Strang Print Room at UCL to see a small exhibition of Henry Tonks’ drawings of WWI servicemen with facial injuries. In western art, the face is a primary marker of identity and humanity, and its violation or absence often represents the limits of the human. Tonks’ portraits are almost unbearably intimate studies. They record men before and after reconstructive surgery: almost certainly in pain, physically and emotionally exposed, but stoical. A surgeon himself, as well as a professor of anatomy and drawing at the Slade School of Art, Tonks managed to reveal something new about the depths of the human face and the ways in which images – and institutions – can shape the way we see. He once wrote that he wondered what the body must look like to someone without his knowledge of anatomy. I wonder if his ability to look without horror or embarrassment at the men he drew allows us to see them differently as well.

What excites you about this topic?

I’ve always liked the idea that the things we take most for granted, the things that feel inevitable and personal – our bodies, emotions or sensations – have a history. My current project focuses on the human face, which has tended to be overlooked in histories of the body.

Each chapter of Portraits of Violence revolves around a particular image or set of images:

- Nina Berman’s 2006 World Press Photo winning portrait Marine Wedding is discussed alongside Stuart Griffiths’ photographs of British veterans of the Iraq War;

- Henry Tonks’ drawings of WWI facial casualties are compared to the medical photographs of the same men in the Gillies Archives; the production of portrait masks for the severely disfigured is approached through the lens of documentary film and photography;

- and in the final chapter the haunting image of one of Tonks’ patients at the Queen’s Hospital reappears in the first-person shooter game BioShock, provoking an exchange on a players’ discussion forum about the ethical limits of realism.

What is challenging about the research?

Photograph of Henry Tonks in his room at the Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup, 1917

Like most researchers working on issues of stigma and appearance within the humanities, my approach is informed by a social model of disability, according to which beauty, normality, acceptability and ugliness are in the eye (and cultural imagination) of the beholder. One of the strange things about disfigurement as a topic is that people (both experts and popular writers) have tended to assume that the object of study is self-evident. We think we know what we’re talking about when we refer to disfigurement. In fact there are no sources – historical or contemporary – that define this problematic term. The sociologist Heather Laine Talley observes in her book Disfigurement and the Politics of Appearance that the concept of disfigurement has ‘no static intelligibility, no objective point of reference, no stable shared meaning’ (2014, p. 14).

This problem with definitions presents a challenge for historians. If we understand ‘disfigurement’ – and stigma generally – as negotiated and context specific, then the idea of a history of disfigurement is a bit misleading. Really, one would need to ask why and how facial or bodily difference becomes disfigurement within particular social interactions and cultural contexts. In the early twentieth century – the period I’ve looked most closely at – these contexts include the fear and censorship of facial war injuries, and the lingering stigma of syphilis, but the symbiotic relationship between war and medicine had a role to play as well. Thanks to the large number of facial casualties returning home from the battlefields of WWI, plastic surgery – described by the pioneering surgeon Harold Gilles as a ‘strange new art’ – became a recognized medical specialism, and disfigurement a treatable condition.

What are the potential impacts of your research on everyday life?

Appearance plays a crucial role within social hierarchies. Like gender, class and race, the way we look is a powerful determinant of social mobility and physical capital. In this respect, there are clear parallels between the civil rights and feminist movements, and more recent developments in disability rights and ‘face equality’.

Despite the inclusion of serious disfigurement in the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) in 1995, there is a widespread perception among disability scholars and campaigners that the norms of acceptability are becoming narrower: that society (at least in the developed and increasingly globalised world) is becoming less tolerant of people who look different from a prevailing idea of normality.

Although disfigurement is not an illness – or even, in most cases, a functional impairment – it is widely perceived as having and requiring a medical solution. Understanding the social, political and historical contexts of ‘disfigurement’ is important both from the perspective of the medical humanities, and for scholars, artists, activists and policy makers working in the field of disability studies and advocacy.

What kind of a research environment is Birkbeck to work in?

One of the things I love about working at Birkbeck is that I teach students with such diverse interests and backgrounds. Each year I run an MA option called Exhibiting the Body, on medical museums and the historical intersections between art and medicine. Over the years my students have included nurses, GPs, painters and performance artists, a game developer, a medical photographer, and the curator of Barts Pathology Museum. There have been some memorable debates along the way on topics ranging from 19th-century freak shows to the ethics of displaying human remains.

As a teacher, being able to draw on a wide spectrum of personal and professional perspectives makes for an incredibly rich classroom experience. In the humanities we talk a lot about the value of interdisciplinarity at the level of research, but often overlook the benefits of teaching students in a multidisciplinary environment.

Find out more

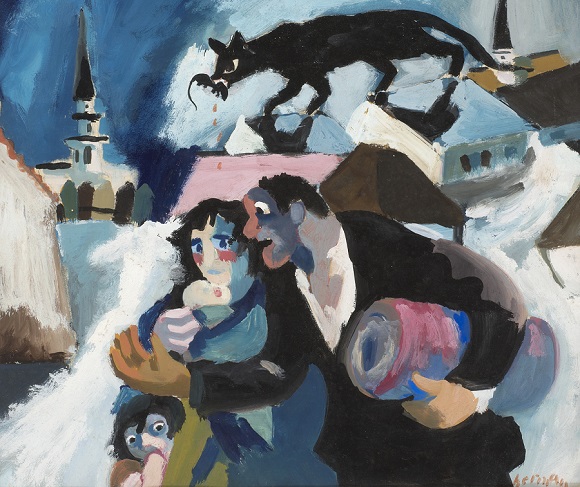

Image credit: Josef Herman, Refugees, c.1941 © Josef Herman Estate, with kind permission, Ben Uri collection.

Image credit: Josef Herman, Refugees, c.1941 © Josef Herman Estate, with kind permission, Ben Uri collection.