Professor Yunus Aksoy shares how ageing populations impact the workforce and discusses possible policy responses.

Professor Yunus Aksoy shares how ageing populations impact the workforce and discusses possible policy responses.

Ageing populations are a global phenomenon. They are caused by two main trends:

- Fertility decline: the number of children per woman in a population has been slowly decreasing since the 1990s.

- Declining mortality rates: people are living longer due to medical advances and lifestyle changes.

These demographic structure changes have wide-reaching impacts in the short and medium/long term. However, the fact that their impact is not visible day-to-day means that they are relatively less discussed in everyday policymaking. My work with my colleagues Professor Ron Smith at Birkbeck, Dr Henrique Basso at the Bank of Spain and Dr Toby Grasl investigates the impact of ageing populations on macroeconomy in general and brings it to the table in policy circles. I am very pleased to see that the issue has started to be taken seriously by many international organisations like the IMF, ECB, World Bank, BIS and numerous central banks. Our research has had significant impact on the debate.

Economists tend to concentrate on growth, inflation and unemployment rates, and what Central Banks and Finance Ministries can do to stabilise the economy over the short term. However, there are other deep and slowly changing forces affecting the economy about which policymakers can do little. The weak recovery after the global financial crisis has sparked renewed interest in these longer term forces, including demographics, which had often been ignored. As individuals, we are often aware of the adverse effects of ageing, as the years go by. Societies can suffer similar adverse effects from ageing, and most developed economies are ageing.

According to the UN Population Division, almost every developed economy has seen a decline in fertility rates and an increase in life expectancy. As a result, the average proportion of the population aged 60+ is projected to increase from 16% in 1970 to 29% in 2030, with most of the corresponding decline experienced in the 0-19 age group in 21 OECD economies.

In the 1960s, Simon Kuznets suggested that a society consisting of consumers, savers and producers can grow in a sustainable way if the demographic structure was a rough pyramid. Larger at the bottom, where there are the youngest – up to the age of twenty or so – the working age next – then at the top a smaller group of older people. The pyramid is now turning upside down, with the bulge at the top.

Why is the demographic structure relevant?

Our research has examined the impact of demographic structure on economic activity, productivity, and innovation. Demographic structure may affect long and short-term economic conditions in several ways. Different age groups have different savings behaviour; have different productivity levels; work different amounts (as the very young and very old tend not to work); contribute differently to the innovation process; and have different needs. Therefore, changes to the demographic structure of a society can be expected to influence interest rates and output in both the long and short-term.

Our analysis shows that the changing age profile across OECD countries has economically and statistically significant impacts and that it roughly follows a life-cycle pattern; that is, people who are likely to be dependent on state or other forms of support – generally the very young and the old populations – seem to reduce economic growth, investment and real returns in the long-run.

Demographic structure also affects innovation; the economy is less likely to develop and/or patent new innovations/inventions. Similarly, productivity, which is driven by innovation, is positively affected by young and middle aged cohorts and negatively by the dependant young and retirees.

Demographics, innovation and medium-run economic performance

When people expect to live longer, they save more for their retirement and consume less, increasing demand for investment products and causing a decline in their returns. This provides one explanation in the steady decline in real interest rates in OECD countries since the 1980s. But it leaves us with a puzzle. A decrease in long-term interest rates should increase investment, but that is not what we observe. Our estimates show that long-term investment is declining. Our solution to the puzzle is that aging has also lowered the productivity of investment, reducing the incentive to invest, because the rate of ideas production and innovation, mainly done by the young, has reduced.

With fewer younger people in the population, there will be less creativity and ideas. Thus, while the cost of investment finance may be lower due to higher savings of the aging population, there are not enough ideas worth capitalising on and so long-term investment and real output declines. An ageing population also throws up social challenges, such as the provision of care for the elderly and how this can be supported.

Are there solutions?

While immigration may address the shortage of workers in the middle of the age categories, the political problems it raises are such that governments are usually unwilling to develop immigration policies that would truly address the issue. Furthermore, as populations are aging globally, this is not an adequate long-term solution. Giving more childcare support for young parents could help increase fertility rates and this is also related to building human capital starting from a very young age.

Increases in productivity by investing in human capital, education and skills is of crucial importance, as is increased funding for research and development that could bolster a generation of new ideas and create new innovations and investment opportunities. At Birkbeck, we have long understood the importance of lifelong learning that is directly associated with productivity gains for the economy, which in the current climate could help to compensate for a reduced workforce and staggered productivity. Robots and AI could also address the productivity/labour supply challenges, especially if we reach a point where machines can generate innovations and robots might be used more to fill gaps in the work force and provide care for the elderly, but it might make more people unemployed.

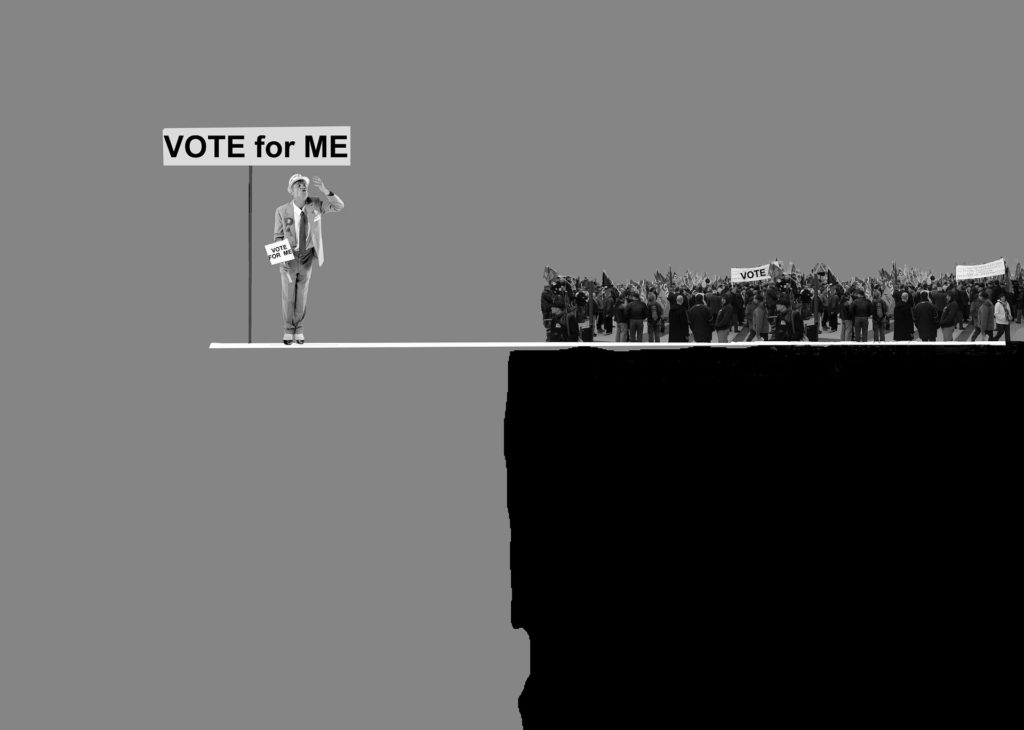

A typical challenge is that politicians are often short sighted. Long-term investment in order to boost human capital and productivity would not be a top priority for an incumbent politician in the short term, despite the transformative effects they could have for the generations to come. Often, what we think is happening now is the slow moving changes that started a long time back, so a long-term view is essential to tackle the economic impact of ageing populations to address the future.

Further Information

Further Reading

- Aksoy, Yunus, Henrique S. Basso, Ron P. Smith, and Tobias Grasl. 2019. “Demographic Structure and Macroeconomic Trends.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 11 (1): 193-222.

- Aksoy, Yunus and Zoega, Gylfi (2020) Fertility changes and replacement migration. Economics Letters 196 (109519), ISSN 0165-1765.