This post was contributed by Dr Peter Grindrod, of Birkbeck’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Read the first post from this series. It was originally published on his personal blog.

It’s been nine months since the last workshop about where the next rover will land on Mars. During that time there have been some fantastic space firsts, including the European Space Agency landing on a comet, and NASA testing a spacecraft that will take humans back into deep space.

But we’ve always kept one eye on Mars. Over the summer the proposed eight landing sites for the ExoMars rover were officially reduced to four. We were really pleased that our two sites got through, but we’ve now got a lot of work ahead of us.

Last week we were in Italy to discuss the detailed geology of the final four landing sites. With ExoMars trying to find life on Mars, we have to decide which one place offers the best chance of finding it. Such a tough call meant it was a fascinating meeting, as each site offers its own advantages and challenges.

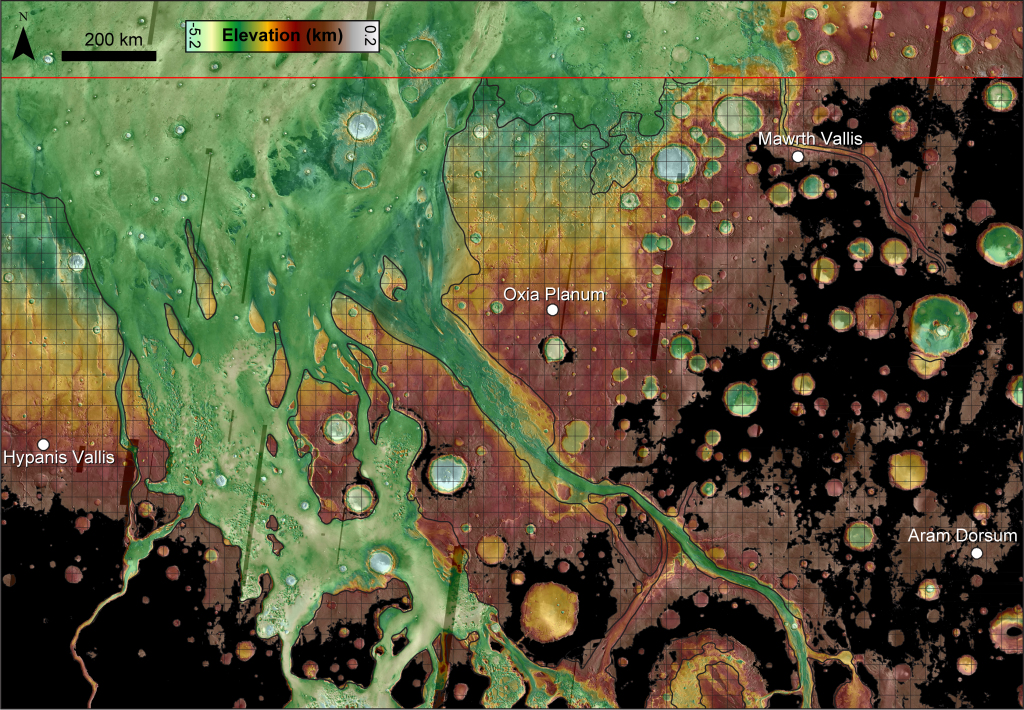

The final four sites are Mawrth Valles, Oxia Planum, Hypanis Valles and Aram Dorsum. Despite all four being in the same region of the planet, they show a diversity that you’d expect from an overall area the size of Western Europe.

Regional context of the final four landing sites for the ExoMars rover. Black regions show elevations that are too high for the rover to land in. (Image credit: THEMIS/MOLA/Peter Grindrod)

Mawrth Vallis, named after the Welsh name for Mars, is a candidate as strong as its namesake’s rugby team. Mawrth made it through to the final four choices for the Curiosity rover, due to its thick sequence of clay minerals – a sure sign of past water that’s also probably neutral in pH (and presumably good for life).

Oxia Planum is about 400km from Mawrth, and shows similar thick, clay layers, but with the added bonus of a channel that may have emptied into a shallow lake. This means we can be even surer of water, which we think is a prerequisite for life.

The landing site at Hypanis Valles is actually at the end of the channel of the same name, and most likely represents ancient delta deposits. Here we think sediments, and hopefully life, were laid down in a low energy environment. This site is good because it might concentrate the evidence for life, thus increasing our chances of finding it.

And finally Aram Dorsum, which was such an unknown before the last meeting it actually had a different name. At the time there was no feature nearby that we could use to name our landing site. So in the end we had to officially apply to name the site. Despite my attempts to name it after the River Irwell, whose tiny tributary flowed through my village when I was growing up, it was deemed to be a positive relief feature and thus needed a different name. So Aram Dorsum it is.

That positive relief at Aram is something that isn’t immediately familiar, although there are quite a few similar features on Earth. It’s basically an inverted river system, where water carves a channel, deposits sediments that then become cemented, while everything outside is eroded away by billions of years of erosion. After this you’re left with a river system, albeit with positive relief. So again, water was flowing through this region, probably about 3.8 to 4 billion years ago, a time when life was probably just getting started on Earth, and possibly Mars.

Now it’s a matter of figuring out the complicated history of what has followed at all sites since the water disappeared, and what it means for the possible evidence of life. Can rocks rich in fossilised microbes survive the bombardment from meteorites? Do these meteorite impacts actually make it easier to get at the deeper rocks, which could have been warmer and wetter?

So part of what we did last week was to assess the complex histories at each site, discuss the likely habitability of the environments we think were around when the features formed, and ultimately what it all means for life.

The other part was to listen to the safety assessments carried out so far on the sites. All the four sites met the global engineering constraints, but local factors such as small, but steep slopes, or the presence of too many sand dunes, increase the risk when it comes to landing on Mars.

So although the science might be great, we’ve got to hope that there are no engineering show-stoppers at this stage. As the Philae lander showed, landing on another planetary body is difficult. So I’m happy to keep figuring out the science of where we’ll go, while the engineers work out how to get there in one piece.

While increasing maternal age, especially for women from their mid to late 30s onwards, is linked to the likelihood of more medical risks for mother and infant, recently published research by my team at Birkbeck, with colleagues at UCL, indicate that this change to older motherhood could lead nationally to better child health and development, and to fewer parenting problems. The studies, based on two large samples – the Millennium Cohort Study and the National Evaluation of Sure Start – found that:

While increasing maternal age, especially for women from their mid to late 30s onwards, is linked to the likelihood of more medical risks for mother and infant, recently published research by my team at Birkbeck, with colleagues at UCL, indicate that this change to older motherhood could lead nationally to better child health and development, and to fewer parenting problems. The studies, based on two large samples – the Millennium Cohort Study and the National Evaluation of Sure Start – found that: