Professor Morten Huse discussed making an impact at different stages in the scholarly life cycle in his second talk for Birkbeck’s School of Business, Economics and Informatics.

On Tuesday 15 March, Birkbeck’s School of Business, Economics and Informatics was delighted to welcome back Professor Morten Huse for the second talk in a series discussing ‘How to become and thrive as an impactful scholar.’

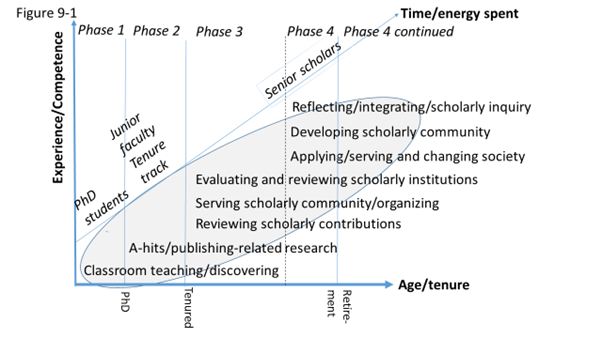

The series, organised and chaired by Dr Muthu De Silva, Assistant Dean (Research), aims to develop Birkbeck’s scholarly community and to support academic colleagues in their research endeavours. The second talk, ‘Thriving at different stages of an academic career’ draws on insights from chapter 9 of Morten’s book ‘Resolving the crisis in research by changing the game’.

Morten encouraged attendees to consider their academic career as a life cycle, reflecting on his own experience of being affiliated with many different universities and the lessons learned along the way. He reflected on some key philosophies that have guided his academic career:

- ‘Ritorno al passato’ – the need to reconsider the modern approach to scholarship.

- ‘From POP (publish or perish) culture to a sharing philosophy’.

- ‘Life is too short to drink bad wine’ – we don’t have unlimited time, so it is important to prioritise what matters most.

What is true scholarship?

Morten commented: “It is easy to think that we are measuring scholarship by publications,” arguing that, as early as the 1990s, academics were already feeling pressurised to publish in certain journals. This has resulted in ‘hammer and lamp syndrome’, where scholars address problems that are already under the lamp, i.e., where data is already available, instead of seeking out difficult problems, as this is an easier route to getting published. Similarly, Morten explained: “If you have a hammer, you see the world as a nail and will look for the easiest way to getting published.”

Reflecting on Boyer (1996), Morten argued that scholarship is not what scholars do, but who they are. When aiming for excellence in research, the goal should reach beyond getting published to thinking about the impact research is having. According to the European Research Council, excellence in research involves:

- Proposing and conducting groundbreaking and frontier research

- Creative and independent thinking

- Achievements beyond the state of the art

- Innovation potential

- Sound leadership in training and advancing young scientists

- Second and third order impact.

Defining your scholarly ambition

Morten noted that academic careers can look different for everyone and that scholarly ambitions are personal and will vary. Career paths can take a teaching, administrative or research route and reach could vary from local, national, to global.

Morten reflected: “It’s easy not to do the proper reflections, integrations and scholarly enquiry. It’s easy not to make a contribution to developing the scholarly community. It’s easy not to give priority to doing something for society. In reality, the scholarly life cycle is not just about getting published; there is so much more that is needed.”

He shared an image of what the scholarly life cycle could look like, enabling senior scholars to give back to junior colleagues:

We would like to thank Professor Huse for a thought-provoking presentation and discussion. The next event in this series will take place in May, where we hope to have the opportunity to bring our community together in person. Details to follow soon on the Department of Management events page.