Christine Slobogin, PhD candidate in the History of Art discusses an Arts Week event about the history of Syphilis.

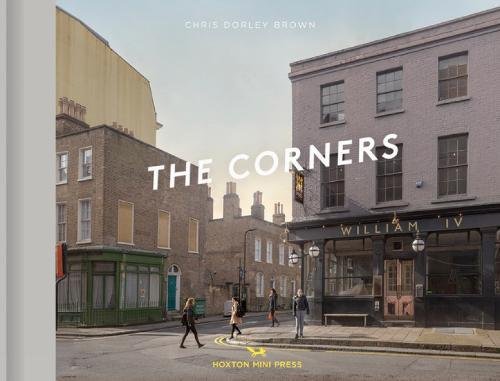

Image: Syphilis, Richard Tennant Cooper, 1912

Dr Anne Hanley began her talk this Monday with: ‘Welcome everyone, to this afternoon of syphilis,’ going on to give a trigger warning that if any audience member did not want to see ‘ulcerated genitalia,’ then perhaps this paper may not be for them. This arresting introduction set the tone for the entire presentation, rife with images of the ulcers that Hanley had promised but also full of thoughtful discussion on narratives of disease, widespread cultural fear, bleak Victorian literature, and propagandistic film.

The main purpose of Hanley’s paper was to trace the shift in the way that syphilis was depicted in Britain’s public imagination between the Victorian and interwar periods. Because syphilis was such a stigmatised venereal disease (VD), men and women who were infected, as well as their relatives were more likely to suppress their stories about their experiences rather than write them down or describe them in another way. Therefore, historians are often thwarted as they search for patient’s perspectives on what it was really like to experience the pustules, the deteriorating nasal cartilage, and even the sink into insanity associated with neurosyphilis.

A large factor in the stigmatising nature of the disease was that it led either to the grave or to the asylum. And this was the narrative that was espoused by Victorian authors when writing about syphilis. Hanley described how novelists used the illness as a plot point to show the medical and moral consequences of transgressing sexual mores and expectations of the time. These stories told about syphilis often followed a similar trajectory, in which a woman and her children are ruined by the moral wrongdoings of the husband. The woman, expected to be innocent and therefore ignorant of sexual matters, can become an easy victim of a morally-suspect spouse and a rampant venereal disease.

This lack of knowledge was compounded at the doctor’s office once the woman sought treatment for her worrying and mysterious illness. Hanley described various medical men who used dangerous paternalism to justify keeping syphilitic women in the dark about their health. After all, the truth could result in a broken home and the damaged reputation of her husband. Often the treatment of these ill women would carry on under the pretence of a different disease, without the patient knowing the full extent of her condition. But sometimes the husbands prevented treatment from happening or from finishing for fear of the monstrous syphilitic truth coming out.

Women could stay ignorant of the risks and symptoms of venereal diseases in the Victorian era because public health information was scarce. The only stories that were told about syphilis were those in the plots of the novels previously described. But this double standard of men having all of the knowledge and therefore power when it came to syphilitic infection began to shift in Britain in the interwar years. The British Social Hygiene Council was established and with it came advertisements for VD clinics through posters and word of mouth but, most importantly, films.

These cinematic visualisations of syphilis contained narratives distinct from the bleak and fatalistic ones of the Victorian-era novels. These films were often light and entertaining moral tales crafted so that viewers could identify with the characters. In one, Any Evening After Work (1930), a man contracts a venereal disease and considers forgoing treatment until his daughter is afflicted with the illness. While the film does use scare tactics to get people to have themselves checked at VD clinics, the overall narrative is that the little girl will get better, and everything will turn out alright—as long as the proper precautions are taken and help is sought.

This shift from pessimistic written narratives to more uplifting and informational films caused an increase of British people going to VD clinics (with both diagnosable diseases and with false alarms). Both ways of telling stories about syphilis fostered an atmosphere of syphilophobia, but the films fulfilled their propagandistic purpose of improving Britain’s sexual health. Hanley argued that to tell stories about syphilis, we need both the fictional and the medical to understand the full cultural narrative of the disease.