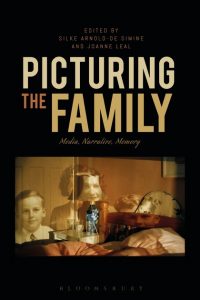

Dr Silke Arnold-De Simine, Reader in Birkbeck’s Department of Film, Media and Cultural Studies, discusses family photographs and cultural memory – the subject matter of her new book, co-edited with Dr Joanne Leal.

In the summer of 2005, during a Visiting Fellowship at the ANU in Canberra, I came across a rather eerie notice in a display cabinet of a small campus exhibition only to see it again and again in the following weeks at the beginning of television programmes and cinema screenings. It advised spectators to ‘use caution viewing these photographs/films, as they may contain images or voices of dead persons’. At first I was puzzled but then I came to understand that in aboriginal society, where people traditionally live in extended family groups, it is considered a taboo to refer to a dead person by name or to look at photographs or film footage of the deceased, partly out of respect but also to avoid painful memories.

As a scholar I was of course reminded of Roland Barthes’s iconic winter garden photograph of his late mother as a young girl, which he famously describes but refuses to share with his readers, and of W.G. Sebald’s omissions in his books, in which family photographs – some reproduced as actual images, some only described – conjure up a mournful mood. What makes photographically captured moments so powerful that they stay with us as a form of ‘afterimage’ even if they have been evoked in another medium such as language? It made me think about what difference it makes if we remember through language, through images, both still or moving, or a combination of mimetic and non-mimetic representations. While it draws out questions around mediated memory, the affective power of photography and the related tropes of death, loss and mourning, my Australian experience was also a stark reminder of the historical and cultural specificity of our encounters with photographs.

The contexts in which we peruse family photographs can be marked as a sad occasion (for example after the death of a family member) or a joyous moment in life (celebrations, birthdays or anniversaries). The viewing experience will not only be influenced by what is depicted and by the occasion that triggers a re-viewing, but also by the formats in which these images are available to us. Are they carefully collected and even annotated in a family album, stored away in shoeboxes or (half-)forgotten in attics? Or are these records of cherished or important moments at our fingertips on camera phones to be shown to a wide circle of acquaintances? Are they framed and on display in homes or in (semi-)public spaces such as social media or archived and exhibited in museums? Do they circulate across different media? Have they gone through a period of being lost, together with the identity of those depicted, to resurface in archives, junk shops or eBay auctions?

If the photographs or photo albums have been displaced and the oral forms of communication which accrue around them have been lost, if they themselves have no annotations or captions, they can be full of mysteries and invite imaginative investment: not only the questions of who and what the photograph shows, but also why, how, where and when it was taken are open to speculation. Who is behind the camera lens? Who do these people in the photograph look at, smile at, frown at? Once they have forfeited their function as family memento, family photographs can lead a complicated after-life in which they become decontextualised and recontextualised, triggering and shaping memories, inviting storytelling, helping us negotiate the past and the future, deconstructing and reconstructing notions of family, kinship and community, and helping us cope with ruptures and (re)establish connections and elective affinities in empathic encounters.

It is important to remember that we perform our identities in relation to the cultural contexts that shape who we are. How we practice intimacy and share our lives with others is determined by the very specific family dynamics in which we grew up, just as much as it depends on the media technologies that are at our fingertips, but it is also historically and culturally contingent. The boundaries between what is considered private and what can be shared with a wider public have experienced a seismic shift over the last few decades: from chat shows and reality TV to social media, blogs and YouTube, ‘sharing’ has become part of how we define our identity as connected beings. We are encouraged to connect to ‘Others’ through empathy, a feeling of relatability that is very much modelled on the notion of kinship and just as often limited by it.

With the increased mobility of people across the globe and the encounters resulting from this, it becomes more and more necessary to question what we mean by ‘family’, ‘home’ and ‘belonging’, to reconceive these concepts so that they enable us to understand and come to terms with the complex realities that we will have to face and to enable us to build alternative modes of social belonging and new forms of community.

With the increased mobility of people across the globe and the encounters resulting from this, it becomes more and more necessary to question what we mean by ‘family’, ‘home’ and ‘belonging’, to reconceive these concepts so that they enable us to understand and come to terms with the complex realities that we will have to face and to enable us to build alternative modes of social belonging and new forms of community.

These are some of the themes that are explored in this collection of essays (edited by myself and Joanne Leal) that introduces a dialogue between academic, creative and practice-based approaches. From the act of revisiting and reworking old, personal photographs to the sale of family albums through internet auction, each of the twelve chapters presents a case study to understand how these visual representations of the family perform memory and identity.

While increasing maternal age, especially for women from their mid to late 30s onwards, is linked to the likelihood of more medical risks for mother and infant, recently published research by my team at Birkbeck, with colleagues at UCL, indicate that this change to older motherhood could lead nationally to better child health and development, and to fewer parenting problems. The studies, based on two large samples – the Millennium Cohort Study and the National Evaluation of Sure Start – found that:

While increasing maternal age, especially for women from their mid to late 30s onwards, is linked to the likelihood of more medical risks for mother and infant, recently published research by my team at Birkbeck, with colleagues at UCL, indicate that this change to older motherhood could lead nationally to better child health and development, and to fewer parenting problems. The studies, based on two large samples – the Millennium Cohort Study and the National Evaluation of Sure Start – found that: