This post was contributed by Dr Peter Grindrod, of Birkbeck’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. A longer version was originally published on his personal blog.

If you had to pick just one place to find life on Mars, where would you go? For the last twenty years, exploring Mars has been a case of “follow the water”. The thinking goes that without water there won’t be life. That could well be true, but it’s only part of the story.

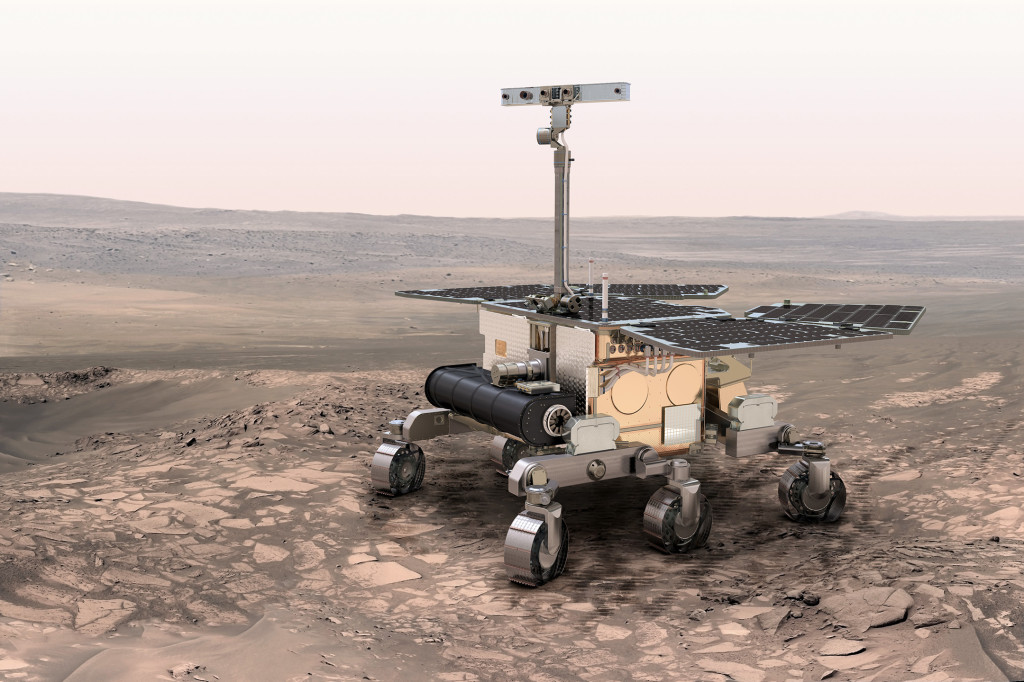

An artist’s impression of the European Space Agency ExoMars rover. Credit: ESA.

In the 1970s John Guest, my former PhD supervisor, worked on the NASA Viking mission to Mars. Twin orbiters, twin landers, nobody builds missions like that these days. As a geologist, John helped to decide where one of the landers would touch down. John told me how he and his friend Ron Greeley only had a couple of days’ worth of images from the orbiters, at a frighteningly low-resolution by today’s standards. They had to choose a landing site that wouldn’t leave the landers in pieces and would still be scientifically interesting. I thought that the pressure and responsibility of that decision must have been massive. John seemed nonplussed by my concern.

The first image returned from the Viking 2 lander on the surface of Mars. Credit: NASA.

I remembered this story because the European Space Agency has recently asked the same question again, and people are trying once more to answer it.

But this is no longer the Mars that Ron and John knew with Viking. Back then Mars was a world of giant volcanoes and enormous rift canyons – planet-scale processes. Today we talk about fluvial sediments and river deltas, redox reactions and energy gradients, clay minerals and organic compounds. We talk about it like we do the Earth.

And we no longer have to rely on just a handful of low-resolution images and a rushed decision. Instead we have hundreds of terabytes of data at our fingertips to call upon in the search.

Technological advances have changed the way we see and explore Mars. The latest images from the HiRISE camera can see things on the surface, from orbit, that are only 25 cm across. It can make out individual rocks. In fact, if you look at modern images of the Viking landing sites, it’s pretty obvious that we would never land somewhere like that again. My god the boulders! It’d be considered far too unsafe nowadays, but I guess that’s testament to the engineering of the Viking landers.

How the decision will be made this time is very different too. It’s a reassuringly long and detailed process these days, carried out in the open by many different scientists.

After the initial call for landing sites back in December, the first discussion workshop will be held in Madrid later this week. Here Mars scientists will come together to champion their own site, debate the pros and cons of others, and generally make sure that no one place is missed. A few months later a shortlist of three or four sites will be drawn up.

Over the following few years, each of these sites will be studied in possibly more detail than any other place on Mars. And then, the year before launch, the European Space Agency will make the final decision.

And I can’t say I envy them. It will come down to a delicate yet familiar balance between engineering constraints and scientific goals.

As it happens, because of the way that we tend to land on Mars, most of the planet is immediately ruled out. All landers use a parachute to slow themselves down as they come through the thin atmosphere. To make sure that the parachute has enough time to do its job, the landers need to touch down at as low an elevation as possible – the more atmosphere it travels through the longer it has to slow down. So, there go all the interesting high areas.

Next, because it’s solar-powered (I presume – there might be communication considerations too), the ExoMars rover has to land in a latitude band straddling the equator that’s only 30 degrees from top to bottom. That’s the polar caps out then.

A blink animation of a global map of the topography of Mars, showing the elevation and latitude constraints when selecting a landing site for ExoMars. Credit: Peter Grindrod.

Finally, landing on another planet isn’t a pinpoint process. There’s a certain probability of landing within a given distance of the target. This uncertainty is known as the landing ellipse, and for ExoMars it’s the equivalent of trying to land in Manchester, but knowing you might end up in Liverpool or Sheffield. Can you imagine the horror? The ellipse for ExoMars is also over four times the size of the ellipse for the recent Curiosity landing, so forget any ideas you had of going to the sites rejected for that mission.

So that doesn’t leave all that much. And we haven’t even started yet on the actual scientific goals of this mission, essentially why we’re going there.

The goals of ExoMars are pretty clear, and pretty bold. The first though has the most control on choosing where to land: to search for signs of past and present life on Mars.

Most of the evidence that we’ve gathered since Viking says that the earlier parts of Mars’s history were the most hospitable to life. It was certainly wetter, probably warmer, and with a much thicker atmosphere than today. So ExoMars has to land somewhere with ancient rocks that are a record of that environment. That means landing somewhere older than 3.6 billion years old. That’s about the same age as some of the oldest rocks on Earth.

And bearing in mind what we know about life on Earth, there has to be evidence of water too, both in the shape of the landscape and in the minerals in the rocks. ExoMars is going to drill two metres into the sub-surface, as exposure to the radiation at the surface might have broken down any evidence of life. So the rocks to drill, core and study are soft, sedimentary rocks that can be read like a history book. Finally, there have to be as many of these targets as possible close to the centre of the ellipse, and as little dust cover as possible.

Over the last few months I’ve been part of a group of UK-based scientists who have been trying to help answer the question of where to land. We knew that other people would propose most of the other well-known sites. So we’re not exactly rooting for the underdog, rather making sure that nowhere is missed. From our own list of about thirty sites, we narrowed it down to just two that met all of the criteria, and which we’ve now sent off for consideration with everybody else’s suggestions.

Later this week we’ll be in Madrid discussing all these sites. I’m looking forward to it, and have to admit that it’s exciting and humbling to have even a small part in the process.

But it’ll be sad for me too. Both John, who was a mentor and friend, and Ron died recently, less than a year apart. They’ll both be missed. It’s strange to think that they’ll both be missing the latest stage of our exploration of Mars that they helped to pioneer.

I’m sure we’ll raise a glass to them. And I hope that wherever ExoMars does land, it’ll be an adventure worthy of future story-telling.