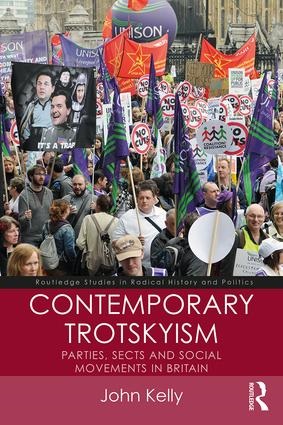

John Kelly, Professor of Industrial Relations at Birkbeck, discusses the social and political dynamics of Trotskyist organisations – the subject matter of his new book, Contemporary Trotskyism: Parties, Sects and Social Movements in Britain.

Almost eighty years after Leon Trotsky founded the Fourth International, there are now Trotskyist organisations in 57 countries, including most of Western Europe and Latin America. Yet no Trotskyist group has ever led a revolution, won a national election or built an enduring mass, political party. If the Trotskyist movement has been so unsuccessful, then how can we account for its remarkable resilience?

The book argues that to understand and explain the development, resilience and influence of Trotskyist groups, we need to analyse them as hybrid bodies that comprise elements of three different types of organisation: the political party, the sect and the social movement. It is the properties of these three facets of organisation and the interplay between them that give rise to the most characteristic features of the Trotskyist movement: frenetic activity, rampant divisions, inter-organisational hostility, authoritarian and charismatic leadership, high membership turnover and ideological rigidity.

As political parties, Trotskyist groups have always been small, never exceeding a membership of 10,000, and their vote shares in general and European elections have been derisory, rarely exceeding one percent. Yet Trotskyist groups are distinct from mainstream parties because in addition to their search for votes, office and policy implementation, they are also sects. This means they are powerfully wedded to the defence of Trotskyist doctrine, a core set of taken-for-granted beliefs that guide their actions and which are considered to provide the blueprint for ultimate political success. Trotskyist doctrine, like religious doctrine, appears in many different forms and struggles over the proper interpretation of Trotskyist and Leninist texts have splintered the movement into seven competing families.

Yet against this record of failure and division, Trotskyist groups have been assiduous in building a number of broad-based and successful social movements, to campaign on single issues. The Anti-Nazi League, created in the 1970s by the Socialist Workers Party, made a significant contribution to the electoral demise of the far right in that decade, whilst the Anti-Poll Tax Federation, created by the Militant Tendency in the late 1980s, helped destroy that Conservative government tax in the early 1990s.

These isolated success stories provide one element in the explanation of Trotskyist resilience, but an equally important factor is their astonishing efficiency in raising funds and building organisational capacity. The income per capita raised by Trotskyist groups from their members is around ten times greater than that of mainstream parties, an extraordinary achievement that allows them to employ large numbers of staff and to publish a wide range of newspapers, magazines and books. These organisational resources enable them to wield a public presence, on demonstrations and marches for example, out of all proportion to their tiny numbers. The same resources, coupled with their vigorous and uncompromising anti-capitalist message, allows them to recruit hundreds of young people each year, many of whom however quit after a short period.

These isolated success stories provide one element in the explanation of Trotskyist resilience, but an equally important factor is their astonishing efficiency in raising funds and building organisational capacity. The income per capita raised by Trotskyist groups from their members is around ten times greater than that of mainstream parties, an extraordinary achievement that allows them to employ large numbers of staff and to publish a wide range of newspapers, magazines and books. These organisational resources enable them to wield a public presence, on demonstrations and marches for example, out of all proportion to their tiny numbers. The same resources, coupled with their vigorous and uncompromising anti-capitalist message, allows them to recruit hundreds of young people each year, many of whom however quit after a short period.

Drawing on extensive archival research, as well as interviews with many of the leading protagonists and activists within the Trotskyist milieu, this is the first major study for thirty years of this small but vocal movement.

Contemporary Trotskyism: Parties, Sects and Social Movements in Britain is available from Routledge.