Part-time PhD student, Sarah Golding shares her thoughts on how to make academic work more engaging and accessible through illustrations.

How to make research interesting, relevant, funny, useful, or just understandable is a problem many academics struggle with. Researchers are passionate about their projects and want to tell the world, but are they explaining it in a way that the world can understand?

Trying things differently

I am a part-time PhD student who works full-time as an Engagement Specialist and I have been determined to find a way to communicate my academic project to the widest possible audience, especially to the people that are the heart of my work. I noticed that I spent so long explaining the ‘why’ of my project that I lost my audience before I got to the exciting part. I wanted to practice what I preached, so rather than providing just academic text to my work, I thought, would a visual aid help?

Below are two options for communicating my work. Option 1 is the academic summary and Option 2 is an illustrated version. I know which one I prefer, please let me know your thoughts!

Option 1:

The paradox of women’s activism in the Republic of Ireland 1970 – 1989 is a thesis that will highlight the problems that currently exist in the historiography around women and their experiences in Ireland. As it stands, the historiography charts a clear progress towards equality only through the lens of political success. This does not take into consideration the role external factors, such as the EU, played and credits the women’s movement entirely with its own successes. However, scholars who examine these political achievements fail to explore the cultural and social expectations of women in this period. They do not take into consideration the stagnation of gender roles, limited opportunities for women and the rural – urban divide. What might be seen by the women’s movements as ‘liberalization’ tended to affect only the metropolitan lives of the middle-class women organisers within the women’s movements.

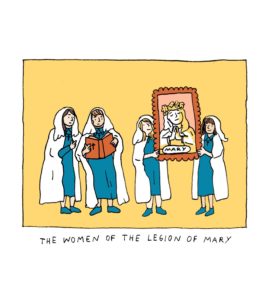

This thesis explores whether there were other types of activism happening in Ireland during this time, that has either been overlooked or ignored. It will focus on four groups of women: the women’s movement, the lesbian liberation movement, the Legion of Mary, and the women of the Magdalene Laundry. It will apply a new theoretical lens that integrates Collective Memory Theory, Social Movement Theory, and the Theory of Everyday Resistance to highlight the ways in which individual actions could be seen as acts of resistance. By looking at these groups of women, the thesis explores women that are grounded in the social framework of the country, it will decentralize the narrative from Dublin and provide a rural voice to the narrative of women’s lives in Ireland.

Did you skip any of that? I would be impressed if you didn’t.

Large sections of text are not that engaging; people used to skim reading for the most useful sections will not see the nuances of the work.

Let’s try again with illustrations…

Option 2:

What is the paradox of women’s activism? The accepted history of women in the Republic of Ireland has been one of progression since the 1960s. But this considers only one group of women, the women’s movement, because of their success of moving into politics. It does not consider the rural-urban divide, traditional gender roles or the subversion of other groups.

To understand more about the activism happening during this period, this thesis will focus on four groups of women.

It seeks to understand if the women’s movement, in a bid to be deemed successful, unintentionally excluded other groups of women from the historical narrative and to bring all four groups under the same umbrella term of ‘women’s activist’.

Better? I think so.

Speaking across the academic divide

One might argue that the same level of detail is not given in the second option compared to the first. This is the point; Option 1 provides no space for natural interest or for your audience to want to ask questions. Option 2 on the other hand, is eye capturing and the audience are likely going to want to know more about how I think I can bring the women mentioned under one umbrella.

Illustrations are a useful tool that have better enabled me to communicate my work. They speak across the academic divide and create opportunities to start a dialog on your work that is interesting to all parties and not just to people who feel the same passion as you.

Commissioning the artwork

Finding an artist whose work I liked was the hardest part of the process. I found Lesley Imgart through the Wellcome Collection. It was her ability to add emotion into her art that enticed me. I reached out via email and briefly told her my idea. We agreed on the commission price and the expected outcomes. The process was fascinating to a non-artist like myself: the work she put into understanding the clothing and colours of the period was unexpected but very beneficial. She also provided me with two colour options, as seen below. If you would like to know more about Lesley, you can find her website here. Alternatively, she has a specific blog about the creation of my artwork here.

Written by Sarah Golding, PhD Student in the History at Birkbeck, University of London.

Twitter: @sarahgolding923

Illustrations done by Lesley Imgart

Twitter: @imgart, Instagram: @lesleyimgart

Further information: