How is the damage of major global disasters paid for? And who by? Dr Rebecca Bednarek, Senior Lecturer in Management at Birkbeck, explores this in new book Making a Market for Acts of God, now available from Oxford University Press.

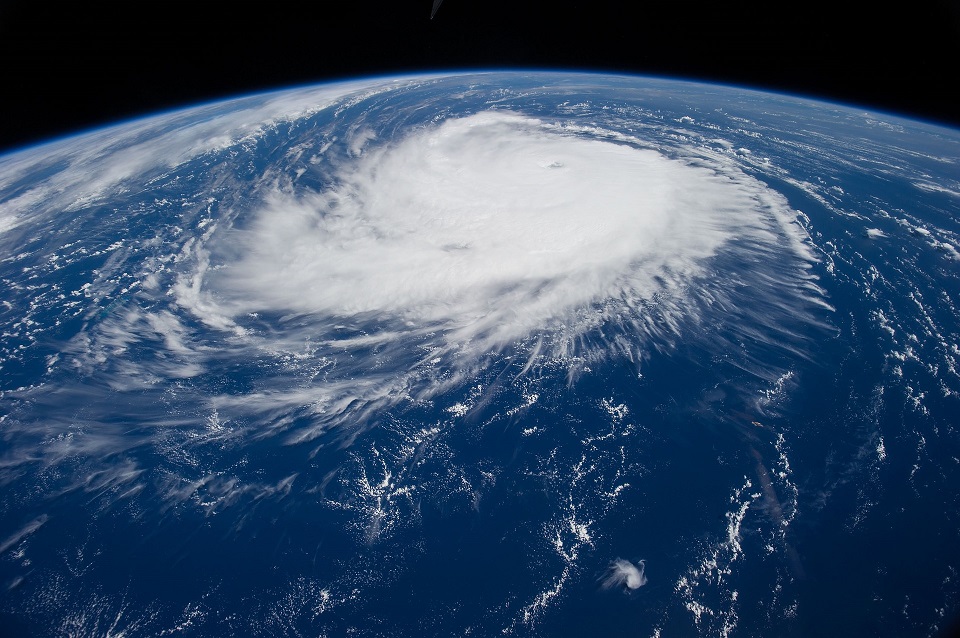

Catastrophic events appear to be increasing in both frequency and severity globally. The financial cost of their losses can be sudden and huge – but who pays the insurance bill for such massive events? Who paid for Hurricane Katrina, or 9/11, or the 2011 Tohuku earthquake?

It all comes from the ‘Reinsurance’ industry – a financial market that trades in the risk of major disasters. This means reinsurance is a crucial social and economic safety net that helps to mitigate some of the effects of disasters, both financially and in terms of allowing for a swifter rebuilding of people’s day-to-day lives following destruction or damage. Dr Rebecca Bednarek, Senior Lecturer in Management at Birkbeck uncovers the everyday realities of the reinsurance market in her book, Making a Market for Acts of God, co-authored with Professor Paula Jarzabiwski and Dr Paul Spee. They get to the bottom of how the risk of such disasters can be calculated and traded in a global market.

In a recent interview for BBC Radio 4’s programme Thinking Allowed, Bednarek explains: ‘In the reinsurance industry, the increase and frequency of weather related events are put in the context of climate change. In addition, what is also happening is increased urbanisation; as cities get bigger, the losses and expenses of these events become more expensive, as more people are insured in localised settings.’ Further, increasingly, a natural disaster in one country could affect significant losses to supply chains in businesses around the world, and it is against this backdrop of increased globalisation that we must attach more significance to understanding the market of reinsurance.

In a recent interview for BBC Radio 4’s programme Thinking Allowed, Bednarek explains: ‘In the reinsurance industry, the increase and frequency of weather related events are put in the context of climate change. In addition, what is also happening is increased urbanisation; as cities get bigger, the losses and expenses of these events become more expensive, as more people are insured in localised settings.’ Further, increasingly, a natural disaster in one country could affect significant losses to supply chains in businesses around the world, and it is against this backdrop of increased globalisation that we must attach more significance to understanding the market of reinsurance.

The sheer scale of the claims means risk must be spread further in order to mitigate its effects – the attacks on the World Trade Centre in 2001 insured losses of $35.5 billion, for example, and for Hurricane Katrina in 2005 the payout was $46 billion. But as Bednarek says: ‘It’s not just the scale of this loss, it’s the fact that you couldn’t predict them. The reason reinsurers are able to themselves survive and to weather such large claims is because for each individual insurance deal, multiple reinsurers take a small part of this deal. No one reinsurer is exposed themselves to a single risk.’ The book also explains how long-term trust-based relationships between insurers and reinsurers are crucial to enabling and stabilising capital flows before and following these large-scale events. These relationships also enable reinsurers to build up deep contextual knowledge of specific risks; something which remains crucial in informing their judgement about risk even as they also use highly technical vendor models and actuarial techniques.

Bednarek and her co-authors shadowed underwriters from various different countries for over three years, gathering ethnographic observations from reinsurers in Bermuda, Lloyd’s of London, Continental Europe and South East Asia, studying their trading activities across many disaster situations.

There may be some developments in the reinsurance industry which could cause future problems, however. Bednarek says: ‘What we found was a whole milieu of long-standing social practices that had ensured that this industry had worked’ and provided capital to underpin large scale catastrophes for centuries. However towards the end of their period of engagement, the researchers began to observe ‘a period of rapid change; things like collatorised forms of finance, different kinds of deals that were changing the industry in certain ways. We wonder what these changes might do to some of these long existing practices that we identified as integral to this market and how it works.’