This post was contributed by Dr Nobuko Anan, lecturer in Japanese Studies at Birkbeck’s Department of Cultures and Language. Here, Dr Anan offers an insight into her new book on Japanese girls’ culture

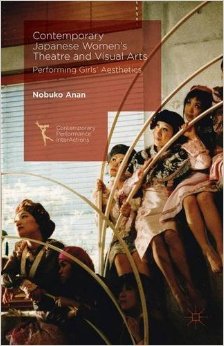

Dr Nobuko Anan’s new book ‘Contemporary Japanese Women’s Theatre and Visual Arts

Performing Girls’ Aesthetics’ (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)

Japanese girls’ culture evokes various images, such as Hello Kitty, cute fighting girls in anime and female students in the sex industry. However, in my monograph, Contemporary Japanese Women’s Theatre and Visual Arts: Performing Girls’ Aesthetics (Palgrave 2016), I have introduced another type of Japanese girls’ culture, which I call “girls’ aesthetics.” These aesthetics are not well known outside of Japan, but are present in many types of contemporary Japanese women’s theatre and visual arts.

An escape from the pressures of Japanese society

Girls’ aesthetics arose in the early twentieth century Japan with the establishment of Western-style girls’ mission schools and the publication of girls’ magazines. These physical places and objects created a space where girls could escape from societal pressures within Japan’s growing empire.

In this space, girls rejected their future as the embodiment of state-sanctioned motherhood, that is, reproducers of culturally and ethnically “pure” Japanese citizens, and instead fantacised same-sex intimacy in (what they imagined as) a tolerant West and romanticised death as a means to reject motherhood. The influence of these themes can be seen in the contemporary period, for example, in the Rococo/Victorian-inspired Gothic-Lolita fashion and boys’ love manga, which are mainly consumed by female readers.

“Girlness” is a state of mind

Although girls’ aesthetics originated in schoolgirl culture in the modern times, one of its important characteristics is that it is embraced not only by female adolescents but also by adult women and in some cases by men. One of the points I have made in the monograph is that “girl” as an aesthetic category does not exclude people based on their sex or biological age. “Girlness” is a state of mind. Indeed, the monograph is about the ways adult women artists make use of girls’ aesthetics as a political tool to challenge stereotypical womanhood.

In these aesthetics, girls’ desire to escape motherhood through an eternal girlhood, which can only be achieved by death as a girl. Related to this, I discuss NOISE’s play about the group suicide of high school girls and Yubiwa Hotel’s production, where girlie adult women use violence on each other as if to help each other to terminate their lives as mothers. This rejection of motherhood can also be seen in Miwa Yanagi’s visual art work, in which time only circulates between girls and old women.

Imagined Westernised spaces

Another aspect of girls’ aesthetics is that they seek to escape the heterosexist and nationalist Japanese reality through imagined Westernised spaces. I explore this within the work of Moto Hagio’s and Riyoko Ikeda’s girls’ manga pieces, which are love stories between androgynous characters in the Western countries.

The two-dimensional nature of manga provides a space for imagining this liberation from material reality. I also examine how this two-dimensionality is captured or lost in theatrical adaptations by the Takarazuka Revue and Studio Life and a film adaptation by Shūsuke Kaneko and Rio Kishida.

While I discuss in great detail the ways girls adore the imagined West, I also explore the dance troupe KATHY, whose members demonstrate Japan’s ambivalent relationship with the West. They portray a nostalgic image of Westernised girls by wearing blond wigs and 1950s-style pastel-coloured party dresses, but they stage failures to dance ballet and other Western-style dances.

While this could be a critique of Westernisation of Japanese bodies, it is less clearly so, because the group is anonymous (the members cover their faces while they dance) and therefore we cannot be certain that they are Japanese.

About the book

Girls’ aesthetics provide a rich alternative conception of women, where many of the traditional dichotomies (e.g., girls as failures as opposed to “fully-fledged” women, Japanese women as the opposite to Western women, etc.) are reconfigured in ways that differ from Western representations of women.

This book is of interest for students in theatre, visual arts, media studies, Japanese studies and gender/sexuality studies.

More information about the book is available here.

Find out more