This post was contributed by Dr Carl-Henrick Bjerström, Lecturer in Modern European History at Birkbeck. This post first appeared on the Hidden Persuaders blog on Friday 15 June 2016.

Earlier this year, Professors Daniel Pick and Paul Preston recorded their conversation about the rediscovery of Alfonso Laurencic, a designer of highly unusual prison cells during the Spanish Civil War. Inspired by their discussion, Carl-Henrik Bjerstrom, specialist in Spanish Republican propaganda, delves into the circumstances surrounding the creation of these cells and the scandals that followed. While Laurencic’s experiments are a strange case within the history of psychological warfare, how they came to be documented by Francoist forces tells us even more about coercion and propaganda within the Spanish Civil War.

“We’ve all got those friends or family members who consider ‘modern art’ a form of torture. Next time they complain about an exhibition you bring them to, just tell them how relieved they should feel that they didn’t fight in the Spanish Civil War […]; they could have found themselves subject not just to actual torture, but torture directly inspired by modernist aesthetic principles”.¹

Colin Marshall’s tongue-in-cheek comment on OpenCulture.com was typical of media responses to the story of Alfonso Laurencic, a Frenchman who designed psychologically disorienting torture cells on behalf of the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War. The story first appeared in January 2003, when El País reported on the findings of art historian José Milicua, and soon spread to news outlets all over the world. Intrigued by the curious case of Laurencic, Daniel Pick, principal investigator of the Hidden Persuaders project, recently talked to Paul Preston, one of the foremost contemporary experts on the Spanish Civil War, to hear whether Laurencic’s innovations amounted to an experiment in psychological warfare.

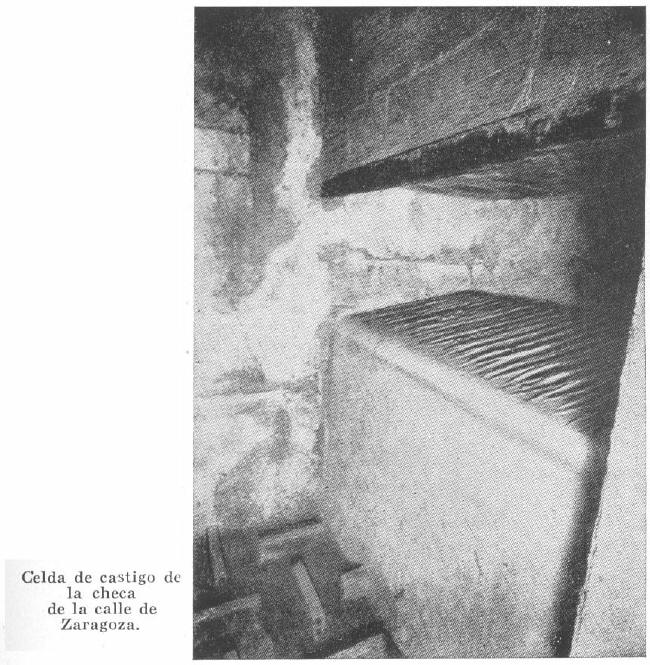

In the context of modern Spain, Laurencic’s bizarre prison cells were certainly unique. Describing the cells’ design, Paul Preston draws attention to bricks cemented to the floor in a zig-zag pattern – designed to hinder any walking in the cell – and to the concrete bed placed as a 45-degree angle, making it impossible for prisoners to lie down without sliding off. Prisoners were also forced to listen to an amplified metronome at different speeds – an innovation probably related to Laurencic’s background as a musician – and were kept within sight of a clock that ran too fast. Such devices were added to maximise the psychological distress of prisoners and perhaps contributed to practices of ‘enhanced interrogation’.

A photo of Laurencic’s cells on Calle Zaragoza, Barcelona.1939.2

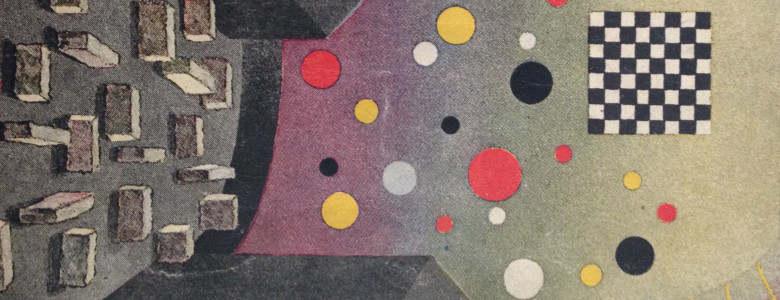

Yet the feature that captured journalists’ attention in 2003 was not the attempt to manipulate prisoners’ sense of time, but the seemingly psychedelic shapes and patterns painted on the prison walls. This obsession derived from a perceived link between Laurencic’s designs and modern art: it appeared as if the visual language devised by artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, foundational and universally revered innovators of contemporary art history, had been converted with surprising ease into an instrument of psychological torture. Among more serious-minded writers there was a sense that Laurencic’s designs may not only speak of the cruelties of civil war but also of a dark potential inherent in the utopian visions that shape our modern artistic heritage ².

However, this view is problematic in several ways, as my reflections below will show. Most importantly, it excludes from accounts of Laurencic’s case its most evident contemporary significance. As Paul Preston emphasises, the story of Laurencic needs to be situated in its proper socio-political context. Once this is done, it becomes clear that it is not a story about modern art but rather a story about the Spanish Civil War and its immediate aftermath.

* * * * *

The Spanish War of 1936-1939 was an unequal battle fought between various forces loyal to a legitimately elected centre-left government, on the one hand, and politically, socially, and culturally conservative supporters of rebelling sections of the Spanish Army seeking to halt the government’s modernising reform programme, on the other. The Republic was from an early stage fighting against the odds, and in spring 1938, when Laurencic designed his cells, the Republican government faced an unprecedented political and military crisis. Rebel forces, led by General Francisco Franco and strengthened throughout the conflict by generous arms shipments and logistical support from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, had launched a blitzkrieg offensive across the north-eastern region of Aragon. Within weeks they reached the Mediterranean Sea by the Valencian town of Vinaròs, thus cutting the remaining Republican zone in two.

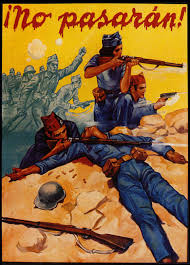

‘They-shall-not-pass!’-Republican-recruitment-poster,-1937

The dire military situation exacerbated internal political tensions within the Republican side. The Republican war effort, which received isolated but vital military aid from the Soviet Union, was weakened by in-fighting. This was due both to resentment caused by the Spanish Communist Party’s influence over political and military affairs and to a de-centralising and collectivising grass-roots revolution pursued by semi-autonomous left-wing forces. It also intensified the hunt for spies and other fifth columnists, known to be operating within left-wing organisations and the Republican Army.

In this sensitive situation, it is perhaps remarkable that Alfonso Laurencic, a music-hall pianist and self-styled architect who had been a sometime member of libertarian, dissident communist, and mainstream socialist unions while making money selling false passports, ended up working for the Republican state intelligence services. But seen from another perspective, he may have had just the skills needed in such desperate times. In their hunt for fifth-columnists, the Republican intelligence services resorted to various shady tactics. Interrogation often took place in so-called chekas: secret prisons first used by radical left-wing groups operating independently of the Republican government. The existence of the chekas was not officially acknowledged by the Republican government but government officials were aware of their continued use throughout the conflict. Cells with the kind of brutal innovations ascribed to Laurencic were uncommon – according to Paul Preston, there were four of them in the Republic as a whole – but their exceptional nature has nonetheless led observers to ask whether they show a hitherto unknown dimension of the Spanish Civil War, evincing the use of sophisticated psychological torture.

However, when details from Laurencic’s trial are studied carefully, the psychological aspects of his gruesome work appear less significant than first assumed. The torture technique used in the Barcelona cells designed by Laurencic were predominantly physical. Descriptions and illustrations in a published contemporary account of the proceedings repeatedly focus on a box in which prisoners were placed and forced to endure hours in excruciatingly painful positions. Even the misleading clock on the wall was not primarily used to disrupt prisoners’ sense of time but psychosomatically, to intensify the sensation of hunger. There is moreover little evidence that any aspect of these designs emerged from real understanding of the psy-sciences. Laurencic referred to the allegedly bewildering patterns and colours on the prison walls as ‘psycho-technic’ additions, but his inspiration in this respect seem to have come not from scientific work but rather vague artistic ideas about the impact of colours on mood. At first sight, this appears to strengthen impressions that Laurencic took inspiration from painters of modern abstract art, especially perhaps, Kandinsky and Klee. Yet on closer inspection even the link between Laurencic’s prison designs and abstract art seems tenuous, as Paul Preston suggests in his conversation with Daniel Pick. Although the actual patterns painted on the prison walls seen in photos of the cells may have been found in paintings by Kandinsky and Klee, they do not necessarily bear more relation to these artists than they do to the geometrical patterns of a chess board or any abstract decoration. Neither did painters of abstract art aim to use their formal exploration as a means to alter psychological states, for good or bad. The one modernist movement which was interested in psychological experimentation was the Surrealists, and, incidentally, a scene from the classic Surrealist film Un Chien Andalou – the opening scene where an eye is slashed open – was shown to prisoners being interrogated in Republican chekas. In this case modernist art did indeed serve as an instrument of torture.

To place abstract art in general in the dock on the basis of Laurencic’s experimental cells, as many commentators have been tempted to do, is not only empirically questionable, but also, as mentioned in the introduction, to miss the real significance of his case. For it was not modern art that was on trial here. In the greater scheme of things, it was not even Laurencic who was the true target of the Francoist prosecution. What was being questioned and judged in the courtroom was, fundamentally, the legitimacy of the Republic that had employed his services. This is clear once we consider the socio-political context of the Laurencic trial and shift our focus to the main source of the Laurencic story: a contemporary book-length account of the court proceedings, written by R. L. Chacón: Why I made the ‘Chekas’ of Barcelona: the court martial of Alfonso Laurencic (1939).³

In his book, Chacón includes several details implicating – directly or indirectly – the Republican government in Laurencic’s crimes. Witnesses testify that ministers in the Republican government knew about the secret prisons but did nothing to close them down. Revealingly, there are also oblique references to the presence in the prisons of foreign agents. Although their nationality is not mentioned, it is clear, as contemporary readers would have understood, that such agents would have been Russians working for the Soviet secret police, the NKVD. Thus, by linking the chekas both to the Republican leadership and Stalin’s henchmen in Spain, the trial, as described by Chacón, appeared to produce further evidence to support the Francoist view of the Republic as a sinister communist plot inflicting pain on honourable ‘Spanish gentlemen’ (a section of the nation to whom Chacón dedicates his book), merely to serve the interests of an evil foreign power. From this perspective, the horrors of the chekas were ultimately attributed to the ideological influence summing up all things abhorrent in the Francoist universe: the so-called ‘Judeo-Masonic-Bolshevik’ conspiracy, believed to be an international force of which the Spanish Republic was but the most recent and threatening expression.

Such references make clear that Chacón’s book served primarily as a propaganda piece justifying Franco’s post-war repression, often taking the form of vengeful mass trials. I have not found further information about Chacón himself, but considering the slogans scrawled on its back pages – ‘Russia is Hell! Franco will save Christian civilization!’ – there can be no doubt that both author and publisher were deeply sympathetic with the Francoist ‘Crusade’, as the civil war was often called by Franco supporters. To them, the Republican experiment had tainted the nation with sin and the political ‘diseases’ of liberalism and socialism, making it necessary for the Army violently to purge the body politic of ungodly and unhealthy elements. Having achieved military victory, the victors moved ruthlessly to exclude from all social and political spheres every group associated with the vanquished, denounced collectively in Franco’s Spain as ‘Anti-Spain’.

Chacón’s book contributes to the dissemination of this narrative; its language and structure even dramatizes it in striking ways. On the surface, Chacón purports to provide a witness account of the procedure. He claims to operate in a documentary mode, mirroring the expected objectivity of the juridical process – an objectivity which in fact was entirely absent in the political trials of the early Francoist era. Yet on closer inspection his documentary account, like all documents, elicits particular responses from its reader by employing a series of literary devices. The scene for Laurencic’s trial is carefully set: the court room is described in detail, as are the reactions of the expectant audience when Laurencic is brought before the judge to testify. The cross examination of the accused and other witnesses is transcribed in the form of a dialogue. Such stylistic choices create suspenseful drama, turning Chacón’s book into something akin to a modern inquisition play.

Indeed, rather than a documentary record, its real function is that of a literary show trial, seeking to terrorise and stoke fear in its readers in order to facilitate the regime’s task of enforcing nationwide obedience. The logic of such propaganda, backed up by credible threats of torture and death, arguably produces a political parallel with methods used in Laurencic’s cells. Francoist trials were not only a way to eliminate the internal enemy, but also a means to keep the entire population on edge. (‘All of Spain is a prison’ was a common saying in the early Francoist years, making the parallel with the chekas clearer.) Chacón’s curiously distorting description of the Laurencic trial serves this goal by showing the implacability with which the regime intended to carry out its ideological project. This project intended to resolve, with brutal force if necessary, the conflicts generated by Spain’s disparate experiences of modernity; conflicts which in this case found their symbolic resolution, described in vivid detail by Chacón, on the morning of 9 July 1939, when Alfonso Laurencic was executed.

1 Colin Marshall, ‘Modern Art Was Used As a Torture Technique in Prison Cells During the Spanish Civil War’, 29 October 2014. See http://www.openculture.com/2014/10/when-modern-art-was-used-as-torture-during-the-spanish-civil-war.html.

2 The clearest example is a video by Elise Rasmussen entitled ‘Checa’. Seehttps://vimeo.com/137291870.

3 Orig. Por que hice las ‘Chekas’ de Barcelona. Laurencic ante el Consejo de Guerra.

Dr Carl-Henrik Bjerstrom is Lecturer in Modern European History at Birkbeck College. His current research is on Republican print culture during the Spanish Civil War, particularly the role that trench journals played in the Republican nation-building project. His first book, ‘Josep Renau and the Politics of Culture in Republican Spain, 1931-1939: Re-imagining the Nation’ was published earlier this year.

Find out more

With the opening ceremony of the 2016 Olympic games due to take place in a few days (6th August, to be precise) athletes throughout the world will be making their final preparations for the biggest sporting event of their lives. It won’t just be anxious athletes arriving in Rio de Janeiro this week; the international press, hopeful fans and governments will all be alighting for the competition, whose roots famously stretch back to antiquity. The Olympic Games appear as a focal point not just for athletes, but also for governments throughout the world, for whom huge investments have been made in the pursuit of the coveted Gold medals. So, who will come out on top? Fortunately for us, Birkbeck’s Dr Klaus Nielsen, Professor of Institutional Economics, has written a paper that should give us a good idea. Using a combination of results from recent world championships in Olympic sport disciplines, world rankings, taking into account banned or absent athletes and historical comparisons, Dr Nielsen has predicted the winners and losers of the forthcoming tournament.

With the opening ceremony of the 2016 Olympic games due to take place in a few days (6th August, to be precise) athletes throughout the world will be making their final preparations for the biggest sporting event of their lives. It won’t just be anxious athletes arriving in Rio de Janeiro this week; the international press, hopeful fans and governments will all be alighting for the competition, whose roots famously stretch back to antiquity. The Olympic Games appear as a focal point not just for athletes, but also for governments throughout the world, for whom huge investments have been made in the pursuit of the coveted Gold medals. So, who will come out on top? Fortunately for us, Birkbeck’s Dr Klaus Nielsen, Professor of Institutional Economics, has written a paper that should give us a good idea. Using a combination of results from recent world championships in Olympic sport disciplines, world rankings, taking into account banned or absent athletes and historical comparisons, Dr Nielsen has predicted the winners and losers of the forthcoming tournament.