Are the public more likely to re-elect a mayor who invests in long-term development? Yes, if there is social capital. The Department of Management’s Dr Luca Andriani shares the results of his latest research in collaboration with colleagues Alberto Batinti and Andrea Filippetti.

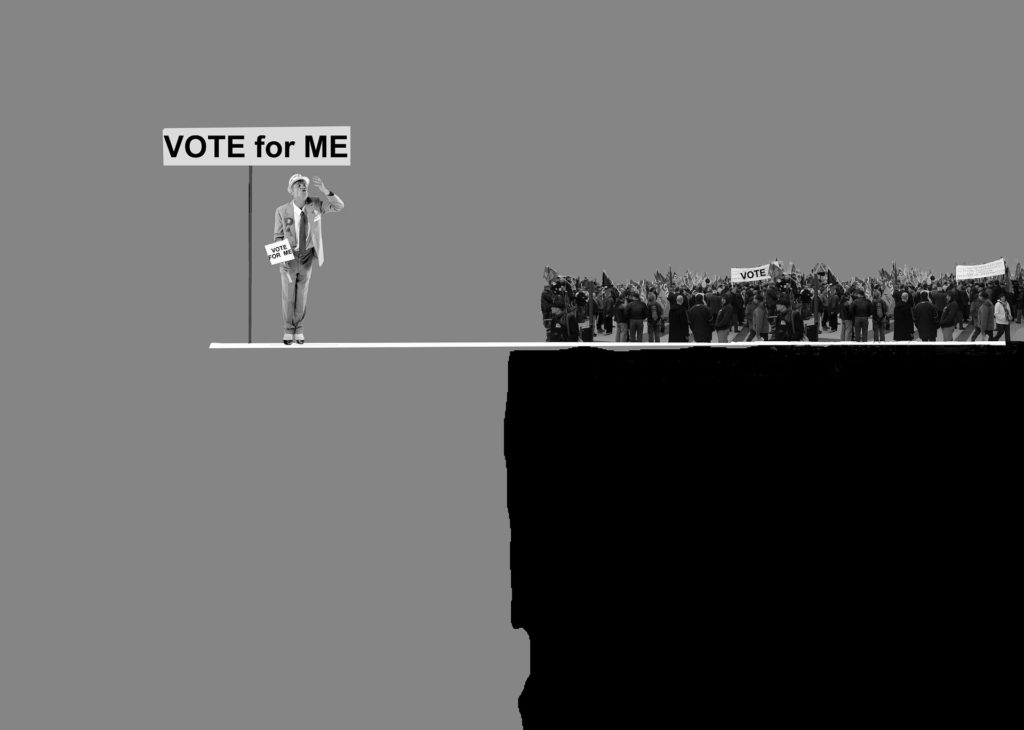

If a mayor is good, she should be re-elected. Prior research tells us that what distinguishes a “good” mayor from a “bad” mayor is the adoption of long-term oriented and transparent municipal fiscal policies. “Good” mayors re-allocate the municipal budget more towards capital investments (rather than current expenditures) and towards property tax, which is more transparent than a surcharge income tax. However, “good” mayors are not always re-elected. In this study, we argue that social capital might be a key reason. In a context with low social capital, municipal long-run fiscal strategy might not be rewarded.

Social capital generally refers to elements of cooperation, reciprocity and mutual trust regulating relations among members of a community. It is generally expressed through the presence of civically engaged citizens preferring leaders and governments that show credible commitments in taking good care of public resources, in acting efficiently and fairly and that adopt long- rather than short-run political economic strategies.

In this study, we look at the Italian context, as this is characterised by a pronounced economic regional disparity between the southern regions recording low economic growth and high unemployment and the more economically advanced northern regions. Italy is also a country with a large disparity of social capital endowment across regions and municipalities for several institutional and historical reasons (Putnam 1993).

Since the late 1990s, Italy has implemented two significant reforms aiming to bring local public institutions closer to the citizens’ needs and preferences: an electoral reform to appoint local governments and mayors and a fiscal reform towards a more federalist system. These changes have been pursued by economically wealthy regions seeking greater autonomy. They were also advocated as remedies to stimulate those administrations in regions that are less developed and efficient.

We test whether the probability of “good” mayors being rewarded, i.e. re-elected, is influenced by the level of social capital endowment existing in the municipality. We investigate this empirically in 6,000 Italian municipalities over the period 2003-2012. We consider the structural dimension of social capital as one referring to the individual’s involvement in associational activities and social networks. This dimension captures citizens’ prosocial behaviour and individuals’ attitude towards planning capacity and forward-looking decision making

Our results show that “good” mayors are more likely to be re-elected in contexts with more social capital. One can speculate that social capital may favour the reallocation of the municipal fiscal budget towards public investment vis-à-vis current expenditures and towards property tax vis-à-vis surcharge income tax, thus enhancing the efficiency and transparency of local public policy.

What does this mean for policy makers?

These results raise important reflections on the implementations of public policies promoting decentralization.

Fiscal federalism theory claims that decentralization improves the ability of local institutions to tailor specific policies aiming to meet citizens’ demands (e.g., DiazSerrano and Rodríguez-Pose, 2015). This gets reflected in the citizens’ satisfaction (e.g. Espasa et al., 2017; Filippetti and Sacchi, 2016). This study qualifies these results, showing that decentralization works relatively well in the presence of high levels of social capital. In social contexts where individuals value forward-looking and transparent fiscal policies, decentralization promotes better public policies and benefits public sector financial performance.

However, this study also advocates that decentralization policies should be coupled with initiatives to improve the capacity of local institutions to stimulate the accumulation of social capital. This could be pursued through two complementary strategies. Firstly, by employing programmes that favour the capacity-building of civic associations, including organizations for environmental, human, democratic rights. Secondly, by enabling these associations to be more involved in local governance. This can be achieved by providing local associations access to formal and informal avenues for participation, engagement and closer monitoring of local public decision-making process.

This blog is based on the following research paper:

Batinti, A. Andriani, L and Filippetti, A (2019) Local Government Fiscal Policy, Social Capital and Electoral Payoff: Evidence across Italian Municipalities. Kyklos 72(4): 503-526