Monica Bohm-Duchen from Birkbeck’s Department of History of Art discusses the ideas that formed the start of the Insiders/Outsiders arts festival and the events taking place nationwide to document the experiences of refugees from Nazi Europe and their contribution to British culture.

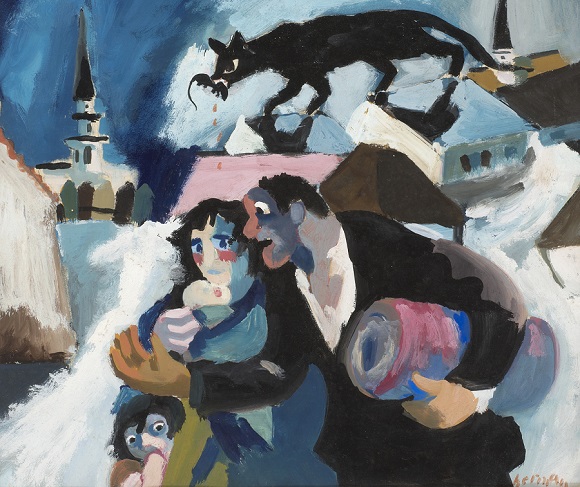

Image credit: Josef Herman, Refugees, c.1941 © Josef Herman Estate, with kind permission, Ben Uri collection.

Image credit: Josef Herman, Refugees, c.1941 © Josef Herman Estate, with kind permission, Ben Uri collection.

As Associate Lecturer at Birkbeck since 2005, I’ve devised and taught a number of deliberately unsettling BA special subject courses, among them Art and War: 1914 to the Present and Art and Scandal in the Modern Period. In 2016-17, I chose to teach a course entitled The Immigrant Experience in Modern British Art, in some ways a natural if belated sequel to earlier projects I’ve been involved with – above all, the exhibition Art in Exile in Great Britain 1933-45, shown at the Camden Arts Centre in 1986.

As the child of parents who both found refuge in this country just in time, the theme of the ambitious cultural project I initiated some two years ago, a nationwide arts festival called Insiders/Outsiders: Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Culture, is understandably close to my heart. But I have little doubt that it was devising the new course mentioned above and realizing the level of student interest in the topic, that also prompted me to undertake this project.

From the germ of an idea, the Insiders/Outsiders Festival has grown beyond my wildest expectations to become an umbrella for approximately 100 events in a wide range of different media at venues across the UK. Clearly, the theme of the festival has struck the right note at the right time. Not only is the cultural terrain richly rewarding in its own right, and the stories of the individual protagonists fascinating and often deeply poignant; but the relevance of these émigrés’ experiences to a world in which debates around immigration are rife and racism is once again rearing its ugly head is unquestionable.

Although the festival is ultimately affirmative and celebratory, its purpose is also to alert today’s public both to these refugees’ experience of profound loss, dispossession and displacement and to the complex challenges – not to say obstacles – they encountered on arrival in Britain.

To my delight, many of my colleagues at Birkbeck have embraced the premises of the festival with enthusiasm. As many readers of this blog will know, the college has a proud history of welcoming refugees as both teachers and students, past and present. Thus, on 9 and 15 March the Birkbeck Institute for the Moving Image (BIMI) is to play host to screenings of essay films by children of refugees from Nazi Europe and Holocaust survivors.

Furthermore, over the summer there is to be an exhibition in the Peltz Gallery curated by Mike Berlin, which will focus on the pioneering photojournalistic magazine Picture Post and its coverage of key moments in the history of immigration to this country: from the Jewish child refugees who came to England in the late 1930s as part of the Kindertransport scheme to the arrival in the UK of increasing numbers of West Indian immigrants from the late 1940s onwards.

Other institutions forming part of the University of London are also participating in the festival. The Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies is running a series of public lectures on relevant topics throughout 2019; while the summer term of the Courtauld Institute’s Showcasing Art History lecture series will be devoted to topics relevant to the theme of the festival.

More academic events currently in the festival pipeline include a symposium being organised by QMUL on the topic of the émigré art historians’ incalculable influence on the discipline in this country. There are also plans for an event focussing on the early history of the Warburg Institute, closely bound up with that of the Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA), which was founded in 1933 as the Academic Assistance Council expressly to help refugees from Nazi Europe – a perfect example of the intimate links between past and present that underpin the Insiders/Outsiders project.

Further information