This post was contributed by Aimee Gasston, a PhD student in Birkbeck’s Department of English and Humanities, whose research focuses on modernist short fiction, the everyday and the act of reading.

My project looks specifically at Katherine Mansfield and food, Virginia Woolf and furniture and Elizabeth Bowen and clothes, and considers everyday practices in relation to reading. I am interested in the ways that short fiction simultaneously fits around and encompasses everyday life – both its ergonomics and elasticity.

In January 2013, I travelled to Wellington to visit the Alexander Turnbull Library and attend a Mansfield conference being organised at Victoria University of Wellington. The Alexander Turnbull Library had recently acquired boxes of new material from the family of Mansfield’s husband, John Middleton Murry. On reading that the new material included recipes, I was eager to go and look for myself and extraordinary research and conference funding from Birkbeck helped me to do this.

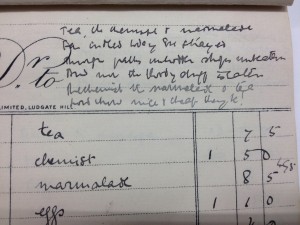

Jottings amid account books. The poem reads:

Tea, the chemist & marmalade

Far indeed today I’ve strayed

Through paths untrodden, shops unbeaten

And now the bloody stuff is eaten

The chemist the marmalade & tea

Lord how nice & cheap they be!

This was my first experience in any archive and it was overwhelming holding papers in my own hands which Mansfield herself had lived with, touched and written upon.

For my stay, I rented a bach in Wadestown that dated from the 1920s, when Mansfield was creating her strongest work. Each morning I wandered to the library down a steep, winding hill that afforded startling views of the ocean, and down past Tinakori Road where Mansfield was born.

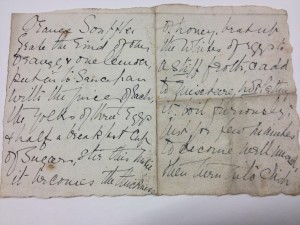

I got to see such a diverse range of materials – from postcards to friends, to notebooks, drafts of stories, as well as shopping lists and accounts with poems about food written in the margins. The material also included recipes handwritten by Mansfield, one for orange soufflé and another for coldwater scones, which, she instructs, must be eaten with ‘plenty of butter’. (For a modern interpretation of Mansfield’s orange soufflé, please see Nicole Villeneuve’s excellent Paper and Salt blog about literary recipes.) I had seen some of the material reproduced in publications but you don’t always get the full sense by reading transcriptions, so even seeing things I already knew about was fascinating.

I also came across a 1923 article in New Zealand’s Evening Post about depictions of meals in literature. This was an exciting find because it uses Mansfield as an example of ‘the inferior sex’ being unable to successfully write about food because they have acquired the ‘snack habit’. The argument of this surprising piece chimed so well with my developing thesis, which considered the short story itself as a type of snack – something you can pick up when you need it, something private, rebellious, sumptuous and (often) decadent.

Mansfield was a plump child and later, when she had contracted TB as an adult, increasingly emaciated. Her letters are full of comments about the food she ate as she travelled Europe in search of healthier climates, as well as comments about her weight. But this interest extends beyond that of an anxious patient – in Mansfield’s writing, food is everywhere. It punctuates both her fiction and her biographical writings, and often she conceives of literature in gustatory terms. This fascination is not only intrinsic to Mansfield’s ambition to relay her experience of the world using each one of her senses, but also evidence of her ravenousness for life. In her first collection of stories, In A German Pension (about which she came to be slightly embarrassed), there are pages and pages devoted to gluttonous eating – but the tone is satirical and there’s distance between Mansfield and her subject matter. So while there’s food everywhere, you don’t quite get the sense of tucking in and enjoying it yourself.

In the later, more mature works, food begins to appear at moments when individuals are negotiating for their own personal freedom and engagement with the world. So you find many more instances of eating alone and snacking in outdoor settings or outside of prescribed norms. Snack food was really beginning to come into its own at the beginning of the twentieth century, with fast food becoming readily available, and the modern short story as we know it came into existence at the same time. My research thinks about the way the instances of snacking in the stories parallel Mansfield’s own coming to terms with the short story as a fictional form (rather than something inferior to the novel or poetry) as well as her success in it. Seeing material relics from Mansfield’s own life has provided me with vital insights, which have shaped and informed this consideration of materiality in her fiction.

[Photographs by author reproduce material available in the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Wellington.]

Further references

- ‘Katherine Mansfield, Cannibal’, Katherine Mansfield Studies, Vol. 5, (Edinburgh University Press), Autumn 2013.

- ‘Consuming art: Katherine Mansfield’s literary snack’, Journal of New Zealand Literature 31:2 Special Issue: New Zealand Cultures, October 2013.

Wow, this dish looks absolutely mouthwatering! The vibrant colors and presentation are truly enticing. I can almost taste the flavors through the screen. I can’t wait to try making this recipe at home and experience these flavors firsthand. Thanks for sharing this culinary inspiration with us.