Dr Kevin Teoh from the Department of Organizational Psychology shares the findings so far from the Firefighter Longitudinal Health Study.

Firefighters working on the Brumadinho Dam Disaster in 2019

Firefighters play a crucial role in the emergency response system, taking on a myriad of roles that range from the firefighting to responding to car crashes, delivering emergency care and raising safety awareness. They also perform rescue services and are involved in disaster relief.

The nature of this work is often physically, mentally and emotionally challenging, and firefighters can be exposed to traumatic situations such as the destruction of property, burn victims, serious injuries and death. All this can eventually take a toll on the mental health of this occupational group, and it is not surprising that firefighters report high levels of burnout, posttraumatic stress and common mental health disorders (Katsavouni et al., 2016; Lima & Assunção, 2011; Noor et al, 2019).

An international partnership

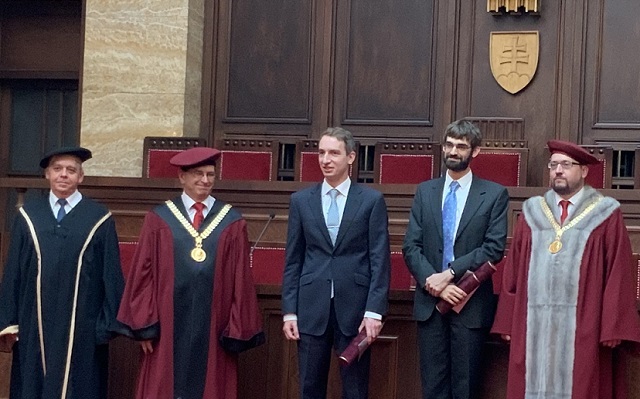

To better understand what, and how, different factors lead to the development of poor mental health in firefighters, in 2018 two psychologists from Brazil – Dr Eduardo de Paula Lima and Dr Alina Gomide Vasconcelos – visited the Birkbeck Centre for Sustainable Working Life for a six-month Fellowship. More specifically, they came from the Minas Gerais Fire Department, whose firefighters received international media coverage when the Brumadinho dam collapsed in 2019, leading to the loss of at least 256 lives.

The cornerstone of our international collaboration is the ongoing Firefighter Longitudinal Health Study (FLOHS), which aims to better understand the dynamic relationships among individual, operational (traumatic) and organisational risk factors in the development of post-traumatic symptoms and other mental health problems in firefighters. Recruits are assessed in their first week of training with follow up data collected every two years.

The role of working conditions

A simplistic take on the poor mental health of firefighters is that this is the product of the challenging work that they do. However, this ignores the fact that there is consistent research showing that psychosocial working conditions can have a beneficial and detrimental impact on our mental health (Harvey et al., 2017). Within the field of organizational psychology, psychosocial working conditions refer to how work is designed, organised and managed. Here in the Department of Organizational Psychology, we have studied this in a range of different occupations, including doctors (Teoh, Hassard, & Cox, 2018), teachers (Hassard, Teoh, & Cox, 2016) and performing artists (McDowall et al., 2019).

The current study

As psychologists, we were not only interested in whether exposure to traumatic events had a link to firefighters’ mental health, but whether psychosocial working conditions had a similar effect. In our first published study from the FLOHS project, we examined the data from 312 firefighters that were part of the first batch of participants. Three types of psychosocial working conditions were measured: how demanding the job is (i.e. job demands), how much influence one has on their work environment (i.e. job control) and how supported one is (i.e. social support). This was in addition to measuring firefighters’ exposure to traumatic events. The findings were quite clear:

- 13% of firefighters reported a level of poor mental health that warrants psychological intervention.

- Higher levels of exposure to trauma and higher levels of job demands were associated with poorer mental health.

- Higher levels of job control and social support were associated with better mental health.

- The strength of the relationship that job demands had on poor mental health reduced when firefighters reported high levels of either job control or social support.

What does this all mean? What if I’m not a firefighter?

The findings show that to support the mental health of firefighters, fire departments should focus on reducing the levels of job demands while increasing the levels of social support and job control. Given the inherently difficult nature of firefighting that will be very difficult to remove or reduce, the very least that firefighters deserve is to work in an organisation where the psychosocial working conditions are not another contributing factor to poor mental health.

This message has direct relevance to workers in other occupations within the emergency services, including healthcare workers, the police and the armed forces. In addition, more generally, our findings emphasise that supporting the mental health of workers requires improvements to their psychosocial working conditions and needs to focus on the organisation itself – not through individual interventions such as resilience or mindfulness training (Kinman & Teoh, 2018).

The citation for the study is: Teoh, K. R. H., Lima, E., Vasconcelos, A., Nascimento, E., & Cox, T. (2019). Trauma and work factors as predictors of firefighters’ psychiatric distress. Occupational Medicine. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqz168

Further information:

References

Harvey, S. B., Modini, M., Joyce, S., S, M.-S. J., Tan, L., Mykletun, A., … Mitchell, P. B. (2017). Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, oemed-2016-104015. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-104015

Hassard, J., Teoh, K. R.-H., & Cox, T. (2016). Organizational uncertainty and stress among teachers in Hong Kong: work characteristics and organizational justice. Health Promotion International, daw018. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw018

Katsavouni, F., Bebetsos, E., Malliou, P., & Beneka, A. (2016). The relationship between burnout, PTSD symptoms and injuries in firefighters. Occupational Medicine, 66(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqv144

Kinman, G., & Teoh, K. R.-H. (2018). What could make a difference to the mental health of UK doctors? A review of the research evidence. London, UK, UK. Retrieved from https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/What_could_make_a_difference_to_the_mental_health_of_UK_doctors_LTF_SOM.pdf

Lima, E. de P., & Assunção, A. Á. (2011). Prevalência e fatores associados ao Transtorno de Estresse Pós-Traumático (TEPT) em profissionais de emergência: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 14(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-790X2011000200004

McDowall, A., Gamblin, D., Teoh, K. R.-H., Raine, C., & Ehnold-Danailov, A. (2019). Balancing Act: The Impact of Caring Responsibilities on Career Progression in the Performing Arts. London. Retrieved from http://www.pipacampaign.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/BA-Final.pdf

Noor, N., Pao, C., Dragomir-Davis, M., Tran, J., & Arbona, C. (2019). PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation in US female firefighters. Occupational Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqz057

Teoh, K. R.-H., Hassard, J., & Cox, T. (2018). Individual and organizational psychosocial predictors of hospital doctors’ work-related well-being. Health Care Management Review, 1. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000207