Research by the Department of Management’s Dr Fred Yamoah and colleagues points to a new way to rebuild the global economy in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

There is no doubt that COVID-19 is first and foremost a human tragedy, resulting in a massive health crisis and huge economic loss.

While the impact on life as we know it has been unthinkable, a side effect of the way of life forced upon us by the pandemic is an unprecedented reduction in global carbon dioxide emissions, which are projected to decline by 8%. If achieved, this will be the most substantial reduction ever recorded, six times larger than the milestone reached during the 2009 financial crisis.

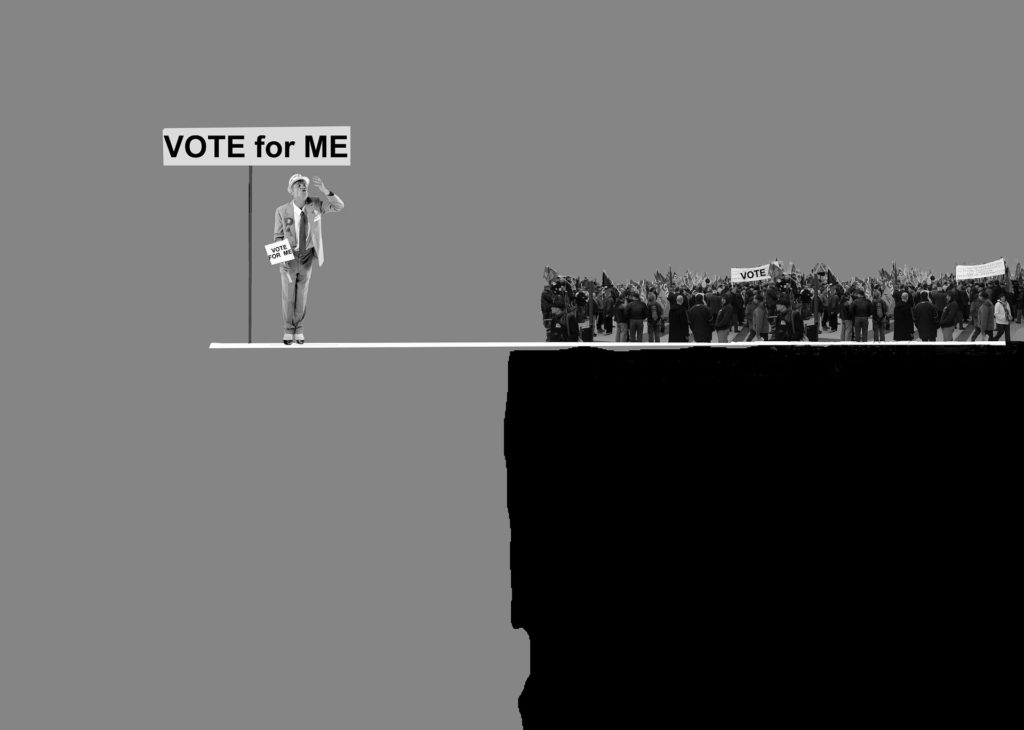

However, these changes should not be misconstrued as a climate triumph. They are not due to the right decisions from governments, but to a temporary status of lockdown that will not linger on forever; economies will need to rebuild, so we can expect a surge in emissions in the future. Indeed, the relatively modest reduction in emissions prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic has proven that zero-emissions cannot be attained based on reduced travel alone; structural changes in the economy will be needed to meet this target.

The case for a circular economy

Before coronavirus prompted this dramatic shift in our way of life, it seemed that the world had been waking up to the need for change to protect our environment. The linear model of our industrial economy – taking resources, making products from them and disposing of the product at the end of its life – jeopardizes the limits of our planet’s resource supply. Girling (2011) found that around 90% of the raw materials used in manufacturing become waste before the final product leaves the production plant, while 80% of products manufactured are disposed of within the first six months of their life. Similarly, Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata (2012) reported that around 1.3 billion tonnes of solid waste is generated by cities across the globe, which may grow to 2.2. billion tonnes by 2025.

Against this backdrop, the search for an industrial economic model that satisfies the multiple roles of decoupling economic growth from resource consumption, waste management and wealth creation, has heightened interests in concepts about circular economy.

What is circular economy?

Circular economy emphasises environmentally conscious manufacturing and product recovery, the avoidance of unintended ecological degradation and a shift in focus to a ‘cradle-to-cradle’ life cycle for products.

In our current situation, there has never been a better time to consider how the principles of circular economy could be translated into reality when the global economy begins to recover. Strategies to combat climate change could include:

- material recirculation (more high-value recycling, less primary material production)

- product material efficiency (improved production process, reuse of components and designing products with fewer materials)

- circular business models (higher utilisation and longer lifetime of products through design for durability and disassembly, utilisation of long-lasting materials, improved maintenance and remanufacturing).

Building back better

A circular economy could also act as a vehicle for crafting more resilient economies. The pandemic has forced a rethink of the way our global economy operates, revealing the inability of the dominant economic model to respond to unplanned shocks and crises. The lockdown and border restrictions have reduced employment and heightened the risk of food insecurity for millions.

To prevent a repeat of the events of 2020, it is necessary to devise long-term risk-mitigation and sustainable fiscal thinking, moving away from the current focus on profits and disproportionate economic growth. Circular economy concerns optimised cycles: products are designed for longevity and optimised for a cycle of reuse that renders them easier to handle and transform. Future innovations under this model would focus on the general well-being of the populace, alongside boosting the market and competitiveness.

This economic model would also support the achievement of social inclusion objectives, for example by redistributing surplus food from the consumer goods supply chain to the local community.

The benefits of a circular economy are therefore obvious in that it strives for three wins in terms of social, environmental and economic impact. The pandemic has instigated a focus on the importance of local manufacturing for a resilient economy; fostered behavioural change in consumers; triggered the need for diversification and circularity of supply chains and evinced the power of public policy for tackling urgent socio-economic crises.

Governments are recognising the need for national-level circular economy policies in many aspects, such as:

- reducing over-reliance on other manufacturing countries for essential goods

- intensive research into bio-based materials for the development of biodegradable products

- legal frameworks for local, regional and national authorities to promote green logistics and waste management regulations which incentivise local production and manufacturing

- development of compact smart cities for effective mobility.

Post COVID-19 investments needed to accelerate towards more resilient, low carbon and circular economies should be integrated into the stimulus packages for economic recovery being promised by governments, since the shortcomings in the dominant linear economic model are now recognised and the gaps to be closed are known. The question is no longer should we build back better, but how.

This blog was adapted from T. Ibn-Mohammed, K.B. Mustapha, J. Godsell, Z. Adamu, K.A. Babatunde, D.D. Akintade, A. Acquaye, H. Fujii, M.M. Ndiaye, F.A. Yamoah, S.C.L. Koh, ‘A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies’ in Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 164. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169