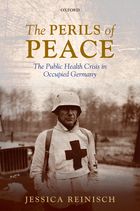

This blog post was contributed by Dr Jessica Reinisch, Senior Lecturer in European History in Birkbeck’s Department of History, Classics and Archaeology. Her new book, The Perils of Peace: The public health Crisis in Germany under Allied Occupation is published today.

This blog post was contributed by Dr Jessica Reinisch, Senior Lecturer in European History in Birkbeck’s Department of History, Classics and Archaeology. Her new book, The Perils of Peace: The public health Crisis in Germany under Allied Occupation is published today.

The Anglo-American occupation of Germany is today often held up as the example of how to occupy a defeated country and has featured in debates about the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. At the time, however, the Allies’ attempts to run Germany hardly seemed to be a cause for celebration or self-congratulation. Much of the hygiene infrastructure had been destroyed and the population was in a state of disintegration, exhaustion and uncertainty. The country was divided into four occupation zones, one for each of the four powers of Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union and France, who pursued different policies and different objectives – soon to be at odds with each other. It was at the centre of the new Cold War division.

During the war German public health was a secondary consideration, an unaffordable and undeserved luxury. Once fighting ceased and occupation duties began, however, panics about epidemics turned ‘public health’ into a principal concern. It was became an indispensable part of their attempts to create order and keep the population governable. Later on, public health work provided a means (sometimes intentional, sometimes not) to return former Nazis into positions of influence. Public health was the crucible for decisions on how the defeated population should be treated, whether and how Nazism could be eradicated, and who should, and who could be, sought out among the Germans as collaborators and helpers.

On World Refugee Day (launched by the UN in 2000 to raise awareness of refugees and their plight across the globe) I want to consider the place of refugees as an important sub-plot in the story of the Allied occupation: a persistent, unavoidable and weighty one. Why? By the time the occupiers moved into their zones of Germany, the continent was already in the grip of one of the biggest (in the aggregate) population movements of the century. By some estimates over 60 million Europeans were moved involuntarily from their homes during the war and its aftermath. They included many different types of ‘refugee’: former slave labourers, concentration camp survivors, survivors of pogroms, evacuees, deportees, prisoners of war, expellees, as well as growing numbers of people fleeing from territories under Red Army control.

Germany was geographically and politically central to this movement. To the occupiers refugees represented multiple threats:

- As obstacles on the roads and transport arteries they threatened to impede the movement of troops, military supplies and, later, occupation forces going into and out of the battlefields.

- As potential disease carriers they threatened to carry infectious diseases to every corner of the globe. Memories of the influenza, cholera and typhus epidemics after the First World War provoked a real panic. In hindsight this proved to be largely unfounded. But the mass of displaced and dislocated people did contribute to two other health concerns: malnutrition and starvation; and rocketing rates of venereal diseases.

- Anxieties about the refugees’ threat of civil unrest were also partly born out. In Germany, liberated slave labourers (who soon received the label ‘DP’, for Displaced Person) were known to seek revenge on their former masters, or to try to get ‘compensation in kind’ by stealing livestock, food and belongings. The occupation armies increasingly saw the DPs as a menace and tended to side with the local German population. Around 8 million of these DPs had to be repatriated to their home countries, which brought its own problems, as a significant number refused to go home to countries now under Soviet control. Some were sent home against their will, while others benefitted from the new Cold War divisions and found refuge in Western European countries or the United States.

Perhaps an even bigger headache for the occupiers was presented by the roughly 15 million ethnic Germans, whose expulsion from their homes in Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, Romania and Russia was often accompanied by outbursts of revenge and violence; possibly as many as 2 million may have died en route to Germany. (These numbers are still fiercely contested). Many of the others arrived in poor physical states and with no means of support.

In 1945, the treatment of these different kinds of refugees was determined above all by whether they were Axis or Allied nationals, and in which post-war and (and, soon, Cold War) sphere of influence they resided. German and non-German refugees were entitled to different levels and kinds of international protection. Inside Germany each occupier also had differing resources, policies and methods of dealing with them.

Out of this chaos came the universalising ambition of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (passed in 1951 and coming into force in 1954). It set out who was a ‘refugee’ (and who could not be, such as war criminals), as well as their rights, and the responsibilities of signatory states concerning their protection. It enshrined the principle of ‘non-refoulement’, that is, it prescribed that no refugees should be returned to any country where they faced a real risk of persecution.

It was a document based primarily on the experiences of Europeans, just at a time when Europe no longer was the main source of refugees. In practice the Convention has been applied to the rest of the world, particularly once the addition of the 1967 Protocol removed geographical and temporal restrictions, attempting to make it truly universal. However, today – 68 years since the end of the last world war, and 62 years since the Refugee Convention – the premise of universalism is being eroded. Earlier this year, Australia, a founding signatory, removed itself from the migration zone to deter asylum seekers arriving by boat; other countries have faced significant internal political pressure to do so. At the very least this is a sad reminder that international mechanisms are only effective as long as its members choose to abide by them.

Dr Jessica Reinisch was a recipient of the Wellcome Trust’s New Investigator Awards. Her new project, entitled ‘Reluctant Internationalists: A History of Public Health and International Organisations, Movements and Experts in Twentieth Century Europe’, will begin in September 2013.

[Homepage slider image credit: Deutsche Fotothek. “Muttertagsfeier im Unrralager”]