This article first appeared in Russian Art and Culture on March 1 2016.

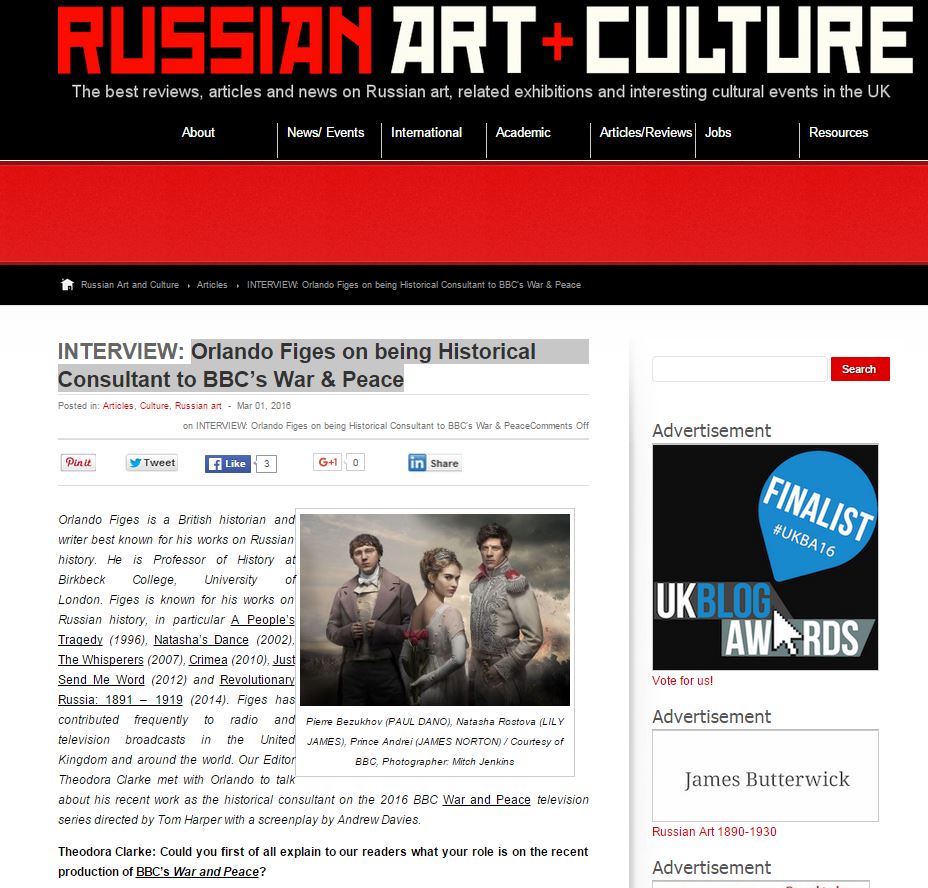

Orlando Figes is a British historian and writer best known for his works on Russian history. He is Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London. Figes is known for his works on Russian history, in particular A People’s Tragedy (1996),Natasha’s Dance (2002), The Whisperers(2007), Crimea (2010), Just Send Me Word (2012) and Revolutionary Russia: 1891 – 1919 (2014). Figes has contributed frequently to radio and television broadcasts in the United Kingdom and around the world.

Theodora Clarke, editor of Russian Art and Culture met with Orlando to talk about his recent work as the historical consultant on the 2016 BBC War and Peace television series directed by Tom Harper with a screenplay by Andrew Davies.

BBC drama War & Peace (C) BBC – Photographer: Mitch Jenkins

Theodora Clarke: Could you first of all explain to our readers what your role is on the recent production of BBC’s War and Peace?

Orlando Figes: I am credited as a historical consultant, and I was approached by the script editor and the production team right from the beginning of their project. I talked to them on a several occasions throughout the production process, even before the scripts were written including about their conception for the programme. They had some ideas they wanted to take out of my bookNatasha’s Dance. I looked at the scripts in all their forms and suggested changes and corrections to historical anachronisms. I also spoke to the cast before they went to shoot, which took five months in Saint Petersburg and Lithuania. Then I also looked at the rough cut of the film to see if there were any howlers in there! Of course, by that stage it was too late to change very much. I could only at that stage point out one or two things. For example, I did not have any control over military uniforms or costumes.

TC: How accurate is the BBC’s adaptation compared to the book? And also how accurate is War and Peace in terms of the actual events the novel depicts, as Tolstoy is writing about real history but in a fictional context?

OF: As you said, the book plays fast and loose with history. There are all sorts of inaccuracies and extensions or condensation of time that Tolstoy plays with. The first question is more relevant in that sense. I think if you have got only six hours to make War and Peace for the screen then the best you can do is to capture the spirit of the book and tell the main storylines. I think the BBC did that very well. But the first thing I said to them was: “Do not try and do a variation of a Jane Austen television series. The Russian aristocracy is a big culture, Russia the country is huge, the scale of the book is epic – you have got to capture that. This is not about squires in small manor houses in the Surrey Hills. This is big time.” I think the series looks spectacular, they have managed to get the scale of Russia and the scale of the book as well.

War and Peace (1966) by Sergei Bondarchuk

Obviously, there are things War and Peace purists might say: “That is not in the book!” or “They have missed an opportunity here and there.” But that would be the same of Bondarchuk’s adaptation. Overall, I think that for a modern viewer it is pretty good adaptation.

Is it true to the book? It is true to the spirit of the book. Is it true to every single representation in the book? No, it is not, but I do not think that you can expect that within the constraints they had. You have to put that into perspective.

As for the question if it is still accurate to the time, a lot of viewers seem to be getting vocal about this and that, but, as I said, it is fiction.

I think one has to bear in mind also, that this is an English language adaptation of a Russian book. For me that was an interesting aspect of being the consultant. One of the things I said to them was that apart from being a huge sort of novelistic, philosophical discourse on how to live well, it is about a very crucial period in Russian history, when this class of Russians discover themselves as Russians. One of the things in the book is about Russianness coming out from under the domination of French civilization, liberating itself. You can see that in the way the book is structured, you can see it in the language. I tried to urge them to reflect some of that in television. Of course, that is almost impossible. How do you reflect the fact that in the course of a book the use of French declines and the language becomes more of what you call ‘prostorechie‘, it becomes more vernacular. I encouraged them to make the contrast between Moscow and St. Petersburg, visually. I encouraged them to try and bring out some elements of folk culture.

TC: I felt the series captured quite well the contrast between the Russian aristocracy and the peasant classes. There was a strong contrast between say the Russian wooden houses on say Count Pierre Bezukhov’s estate, when he visits the peasants on his land, and the grand town houses in Moscow, the Imperial Court and Tsarist balls in St Petersburg.

OF: Yes, I know what you mean. The BBC had this idea of Pierre entering the Rostova Palace at the back, getting through the back yard and pigs. It was the first thing we discussed, because it came out of Natasha’s Dance, where they have been struck by my analysis of the topography of aristocratic palaces, and where there was often a stark contrast between the formal European rooms and the less formal quarters, where Russian ways were in evidence. That is not in War and Peace, but we had a long discussion and they wanted to use it. It is a good example where artistic license trumps historical accuracy. But what can I say – it is up to them. It looks good on the screen, it is true to some elements and spirit of the book.

TC: Why do you think War and Peace is considered such an important work in the history of both Russian and world literature?

Old Count Bezukhov, Pierre Bezukhov, Anna Mikhailovna, Catiche & Prince Vassily Kuragin / Courtesy of BBC

OF: I think it is the greatest. I am not sure if it is a novel, because Tolstoy is insisting that it is not. But I think it is the greatest work of fiction ever written, and I am sure a lot of people, who have read it, would say so. You lose yourself in the book and in the world it creates completely. It transforms you in the process. The whole construction, the emotions and the characters are all just so-so brilliant. There are just so many bits of writing, which are completely unforgettable, better than anything written in terms of being true and being completely believable, even in translation. That is the amazing thing. Even when you are reading it in translation, the language seems to fit reality so well.

TC: It is famously a very long epic novel with hundreds of characters. How did the television series cope with condensing these multiple plot lines?

OF: There are well over a hundred characters, so obviously they have had to reduce those. I think Andrew Davies did amazingly well in the first episode, getting all the characters up and running. There is so much to get going in that first hour, and you have to get to the climatic scene with the death of the old count.

TC: It was beautiful shot throughout. Did the filming mainly take place in Russia?

OF: Not all of it, but they managed to get access to the palaces. Most of the series is shot in Lithuania, like the outside scenes, the landscapes.. And they have got some wonderful outside footage of St Petersburg.

Filming War and Peace outside Catherine Palace, Tsarskoe Selo / Courtesy of BBC

TC: You were involved with preparing the actors before they did their filming. How do you do this?

OF: They were in rehearsal in London and then they spent five months abroad. Tom, the director, wanted me to go along and talk to them, so we spent half a day together. It was important that all the main actors had read the book to understand their characters. It was important for them to understand the context of the time as well as the context of the book. I have done it before with productions of Chekhov in the theatre. The actors want to ask you about their character and how they are playing their character, which could be helped by somebody who knows a bit more about the history and will be able to say: “Well, this would be the educational background they had, or that would be what they would think about so and so..” That was my role to brief them on that.

TC: I went to Yasnaya Polyana last year in Russia and the Director of Tolstoy’s country home was telling to me how his research was very precise and detailed. He visited Borodino and apparently went so far as to even work out where the soldiers would be standing and if the sun would be reflected in the eyes during a charge!

Borodino scene in BBC’s War and Peace / Courtesy of BBC

OF: He did. He spent the day exploring the Borodino battlefield. I think it is a part of it, because he was very much influenced by historians, tying to do total history. That is what the book is about, it is a sort of attempt in fictional form to write something like total history, because history cannot get into the head of people and bring out the emotional, intimate side of history. I think that ultra realism for Tolstoy is about trying to do that – here to take a chunk of Russian history and make it true to life. But adapting it for the television is an absolutely different thing. For example, the end of episode three, the meeting of Pierre and Andrei – it is a major subject in the book, and may be it is only a pale reflection of that on screen, but if you are given six hours, that episode can only take a few minutes.

TC: There are several previous television adaptations of War and Peace including a well regarded Russian version.

OF: Indeed, that is the one by Bondarchuk which is seven hours, so an hour longer than this BBC version. I think the 1970s British one was longer, it was about twenty episodes.

TC: When you were researching your book Natasha’s Dance, how did you find out specific subjects like what they would have been wearing? As the BBC adaptation has some wonderful costumes.

James Norton as Andrei Bolkonsky in BBC’s drama War and Peace / Courtesy of BBC

OF: Military uniform, for example, is very easy because the Tsar’s family was obsessed with military uniforms. So, we have pictures of every hussar regiment, infantry regiment and its uniforms virtually for every period. I think the costumes are pretty accurate.

One of the things Tolstoy wanted to do in War and Peace is to show that 1812 was like a watershed in Russia’s national consciousness. In the book suddenly after 1812 he shows them all beginning to wear Russian dress, kokoshnik headdresses… It did happen, but very gradually over twenty of thirty years, in the reign of Nicholas I, as well as under Alexander I. That was a long, gradual process, and Tolstoy, for fictional purposes obviously, condenses it into a very short time. In that sense I think that gives a TV adaptation certain artistic licence, because Tolstoy was not accurate himself.

TC: I read that originally when Tolstoy wanted to write War and Peace he was going to write about more contemporary history, but then once he started researching, he ended going back further and further in time for the novel….

OF: That is right. Obviously, he began it as a Decembrist novel, having returned himself from the Crimean war and getting interested in Volkonsky and other Decembrists. He met Sergey Volkonsky when he returned from exile, and wanted to write about Russia in 1825, from the vantage point of the reform spirit in Russia under the Alexander II period – so looking back at this earlier period when Russia might have developed on more constitutional lines.

Then he looks into the Decemberists, and he realises that the origins of 1825 were in 1812, in the experiences of the officers like Volkonsky in the army, fighting Napoleon, discovering in their fellow soldiers from the serfs fellow Russians, realising the patriotism of the serf and the democratic instincts of peasant society, and wanting to Russify and democratise themselves. Many of those officers came back from the Napoleonic wars having been to Paris with Western constitutional ideas, some of them pesantysing themselves, as Tolstoy was to do himself, of course, later on. That was the moment of democratisation and Russification, that Tolstoy was interested in. It has to be said, the book is much stronger in its description of aristocratic society, which is the Russia Tolstoy knows, than it is in its description of peasants. I mean the Karataev figure, whom Pierre meets in prison. He is not very believable. Karataev is like a cypher for a sort of good way of living.

Lev Tolstoy at the inauguration of “The Library for the People” he helped to found at Yasnaya Polyana. / Courtesy of andrewdkaufman.com

TC: I remember when I visited Tolstoy’s house, there were pictures, letters and descriptions of him setting up schools for surfs and educating the illiterate peasants. Did he base parts of Pierre’s character on himself? Can we identify autobiographical moments in the novel?

OF: Absolutely, we see it in episode three when Pierre is influenced by Freemason ideas, wanting to live a better life, educate his own peasants; he sets up a school, which Tolstoy tried to do on several occasions. Tolstoy got frustrated on his first attempt, but then he succeeds with a school at Yasnaya Polyana, and it becomes the basis of the whole Tolstoy movement later in his life.

There are elements in Pierre, in his idealism, that are projections of Tolstoy’s own yearnings. But then there are elements of Tolstoy in Nikolai Rostov as well, the whole scene of losing all that money at cards. It is a part of Tolstoy’s own biography too, let’s not forget. And I think you can equally say that in Andrei there are elements of Tolstoy’s scepticism about systems and his fear of death. That was one thing, the scene of Andrei’s death, which was reduced considerably in the original script, and I insisted that it was one of the greatest episodes of world literature, and they had to make more of it in the television episode.

TC: You mentioned your book earlier Natasha’s Dance which was an important resource for the producers. Can you explain what the significant moment is that your title references which is shown on screen and is an important scene in the book?

Count Rostov, Uncle Mikhail & Natasha Rostov / Courtesy of BBC

OF: Yes, my book is named after a famous scene in War and Peace, when Natasha, Nikolai and Sonia after hunting end up in a so-called uncle’s cabin, with vodka and nice things to eat, and Natasha instinctively is able to dance a folk dance, a peasant dance. So, I wrote the introduction around that, and that is what I wanted to bring out in my cultural history. The question Tolstoy asks there: “How could it be that this young countess, in silks and satins, who only danced the waltz, could instinctively dance this peasant dance?” – that is my starting point in Natasha’s Dance. I tried to approach the questions Tolstoy’s scene invites us to ponder: What is this sensibility we call ‘Russiness’? What is it that makes Russians “Russian”?

TC: Can you explain in terms of the series, how long does a programme like this takes to get made? When did you first get involved?

Read the original article on Russian Art and Culture

OF: It was around two and a half years, something like that.

TC: And when you reviewing drafts of the script, are you looking more at how it the programme episodes are historically accurate to the period or how it faithfully presents Tolstoy’s book?

OF: Both. I saw my role as about to make recommendations, that would help it reflect the book, and also to eradicate any anachronisms. However, the first thing they said to me was: “We have to have an artistic licence to do it the way we want to”, and I replied: “Fine.” So, in terms of reflecting the book properly, that was purely down to Andrew Davies. He read the book several times. My role was to make suggestions in terms of the balance. We had discussions about characterisation and I have taken some anachronisms out. But in the end, the final decisions were down to Andrew Davies and the producers obviously. So, the whole incest thing was slightly stretched from the original, but I think also the issue has been rather overblown. We do not see a brother and sister in bed, we just see them being overly familiar. Is that wildly out of the spirit of the book? I think it is up to Andrew and the producers, it is not up to a historian to say to them that it is unacceptable.

TC: Thank you, Orlando.

Natasha’s Dance is available to buy on Amazon here.

Watch the BBC’s new adaptation of War and Peace here.

What does the inheritance system mean for queer people?

What does the inheritance system mean for queer people? The Norwegian gay solicitor Halvor Frihagen strongly advices LGBTQ-people to write queer wills at a young age: “It is important to have thought through and talked about things while still friends. People do not think so much about death when one is young and healthy.” He points out that also same-sex couples should talk about who gets what if the relationship ends or one of the partners will suddenly die. (Nordvåg 2016.)

The Norwegian gay solicitor Halvor Frihagen strongly advices LGBTQ-people to write queer wills at a young age: “It is important to have thought through and talked about things while still friends. People do not think so much about death when one is young and healthy.” He points out that also same-sex couples should talk about who gets what if the relationship ends or one of the partners will suddenly die. (Nordvåg 2016.)