This post was contributed by Melanie Jones of The Mechanics’ Institute Review. This month the Birkbeck Creative Writing department launched its new website The Mechanics’ Institute Review Online. This year marks a huge success for the Creative Writing MA as ten alumni have novels coming out this year.

To celebrate these achievements we are profiling a selection of the authors and extracts from their upcoming novels will appear on MIROnline. Here, Melanie Jones speaks with alumnus Julia Gray about her novel, The Otherlife (Andersen Press, July 2016)

Read an extract of the book at MIROnline

The Other Life, by Julia Gray

MJ: The Otherlife will be published in July this year, what can you tell us about the novel and the themes behind it?

JG: I set out to explore what a rather amoral child might do if he were put under too much pressure; if the expectations for what he should achieve were too great and burdensome. How we deal with situations that demand too much of us is one theme – addiction, violence and escapism all feature in some way. Coming to terms with death is another.

You call on your experiences as a private tutor in this novel but also mix these with the supernatural and Norse mythology. Can you tell us about the process of mixing experience based writing with myth?

I’ve always been fascinated by books in which everyday life interfaces with the surreal or extraordinary. British fantasists like Diana Wynne Jones, Penelope Lively and Susan Cooper do this especially well in my view, and I knew I wanted to try to create this kind of mixture myself. I used my experiences as a tutor and teacher as a basis for the world in which Ben and Hobie live; I also drew quite a lot on my own childhood education, particularly in terms of the rigorous scholarship preparation that the boys go through. In general, these parts were a pleasure to write, since they involved a kind of rapid downloading of whatever memories happened to surface as I went.

The mythology, in terms of how the boys first encounter it, was also based on experience, in so far as I used the stories I’d written (as homework) when I was a child – sometimes word for word – as part of the text. Later, though, I had to do a lot of reading and research: learning a bit of Norse grammar, poring over dictionaries, tracking down esoteric translations in Senate House library. This was also pleasurable, but much slower. I’d say the process of mixing the two was the hardest part, since it was here that the plot became key to the architecture. The other challenge was to manage the incredibility of the supernatural elements; I wanted to preserve a real ambiguity for the reader, and this was hard to navigate at times.

The novel is written from the perspective of a teenaged boy, what was it about this particular voice that you found inspiring?

There are two narrators: sixteen-year-old Ben and twelve-year-old Hobie. Although Ben is the more sympathetic character, I struggled a lot more with his voice than I did with Hobie’s. I’ve spent much more time working with children of Hobie’s age, and I’d say of the two it was Hobie’s voice that I found the more compelling to write.

One of the first things I tried to do was recreate the rhythms of speech found in American Psycho – that kind of relentless, slightly flat tone, namechecking labels and brands, not pausing for breath – and then add dashes of Nigel Molesworth in full Down With Skool mode. What drives Hobie’s narrative is his rage: his frustration with his mother, with the boundaries imposed daily on his life. To write in Hobie’s voice I had to feel his rage, which was sort of refreshing, and then go with it. Ben is a softer, nicer, more thoughtful and sensitive person, but strangely this did not make it easier to write in his voice – all the rewrites I did were of Ben’s narrative. Another challenge was sufficiently differentiating the two voices.

Young adult fiction is increasingly popular with adult readers. Do you have any thoughts on what the genre has to offer readers of all ages?

I think YA has a kind of tautness of voice and a briskness of pace that are probably compelling for many readers. There are big themes, strong characters, absorbing worlds; there are many subgenres to choose from. Sometimes a book with a teen protagonist is marketed as YA, when in fact it might have been originally written for adults: just because it’s targeted to a particular audience doesn’t mean it should exclude a wider readership.

How have your experiences as a musician and songwriter affected your prose writing?

Julia Gray

Music is quite important in The Otherlife – Ben is a massive Metallica fan, as am I. I really enjoyed writing about heavy metal, as it’s something I’ve not had the opportunity to do before. As I worked my way through various drafts I had certain playlists that I always listened to while writing. One was just called ‘Sad Songs’. Songwriting by comparison is a far faster process.

For me the hardest thing was to learn to sit still long enough, and to have enough tenacity and patience, to produce something eighty or ninety thousand words long, as opposed to a set of lyrics on the back of an envelope. From the first chapters (written for Julia Bell’s Writing for Young Adults Workshop) to the final copyedits, I spent exactly three years working on The Otherlife. I found the writing of prose informed my music-making as well.

How have you found the experience of becoming a published author? Have there been any memorable moments along the way?

I was sitting exactly where I am sitting now – on the floor in my living room – when I received an email from Louise Lamont, who is now my agent, asking me to come in for a meeting. (She had been given the manuscript of The Otherlife by another agent.) At this moment, it all started to feel a little bit more possible that maybe one day someone might publish my book.

You completed two Creative Writing courses at Birkbeck, a post-graduate certificate in Children’s Literature and an MA in Creative Writing. How did these courses affect you as a writer?

For me, the deadlines, structure, peer support and the guidance of tutors were all totally essential and I wouldn’t have had the confidence, understanding or ability to write a book in its entirety without having done them.

Can you tell us about your current writing? What’s next?

I’m halfway through another YA novel, which is coming along slowly but surely.

Find out more

- The Mechanics’ Institute Review Online

- Creative Writing at Birkbeck

- Read an extract of Julia Gray’s debut novel

Julia Gray is a London-based writer and singer-songwriter. Her first novel for young adults, The Otherlife, will be published by Andersen Press in July 2016; she has also written a picture book about the endangered Arabian Leopards of Oman, published by Stacey International in September 2014, and has contributed a short story to the eleventh edition of the Mechanics’ Institute Review.

Her most recent album, Robber Bride, was recorded with the support of the Arts Council. Named after the novel by Margaret Atwood, the album explores how turning points in contemporary and ancient narratives can be reflected in song. Julia has a first in Classics from UCL, a post-graduate certificate in Children’s Literature from Birkbeck and most recently an MA in Creative Writing, also from Birkbeck, for which she received the Sophie Warne Fellowship. www.thisisjuliagray.com

Melanie Jones

Melanie Jones graduated from the Birkbeck Creative Writing MA in 2015. She is the Managing Editor of MIROnline and a member of the MIRLive Team. She was a member of the editorial team for The Mechanics’ Institute Review, Issue 12.

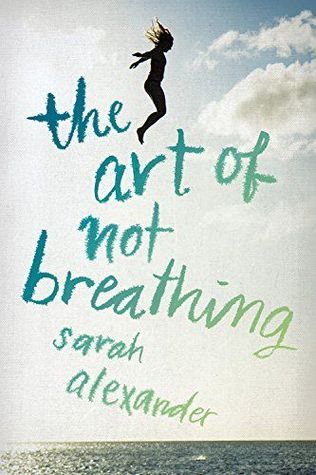

MJ: First of all I want to say congratulations on the upcoming release of The Art of Not Breathing. Can you tell us a little bit about where the idea for this story first came from?

MJ: First of all I want to say congratulations on the upcoming release of The Art of Not Breathing. Can you tell us a little bit about where the idea for this story first came from?